“It’s really hard to do anything when you don’t have much to look forward to. Because then you’re just stuck in the present. There’s nothing to do in the present. It’s here and then it’s gone. The present can be so… empty. So random. Something to look forward to, even something small, gives it all a much better framework.”

Such is the concept explored and, to an extent, yearned for, in Maybe Tomorrow, Boston-based playwright Max Mondi’s meta dark comedy, officially debuting Off-Broadway with Abingdon Theatre Company, under the stalwart direction of company Artistic Director Chad Austin.

Inspired by true events, with the neuroscience of depression and psychosis nestled in between, the play chronicles the relationship of Gail (Tony Award-nominated Elizabeth A. Davis) and Ben (Younger’s Dan Amboyer), a seemingly average couple ten years into a relationship, who devise a “pause room” — in the bathroom of their mobile home — to which they retreat to cool off after a fight, live out their sexual fantasies, or simply relax if they’re just too overwhelmed with life. But when Gail starts to utilize the pause room for more than just a pause, refusing to engage with the outside world, their life, relationship, and perceptions, are tested like never before.

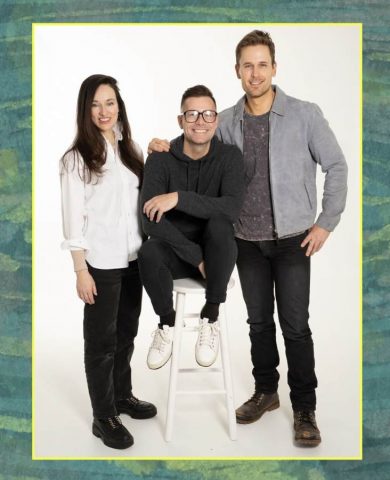

Ahead of the big premiere, we sat down with Mondi and Austin to discuss the play and its origins, as well as the timeliness of its message — and of the play itself — the pros and cons of isolation, and how this piece plays with the idea of what’s real and what’s not.

Have a look at their answers below!

Can you talk a bit about the origins of this piece? What about the topic spoke to you personally? Why was it the topic to tackle, or the play to do?

Max Mondi, Playwright: The idea for the piece first came to me back in 2008. I was a Literary Intern at the Guthrie Theater, and I was working with a bunch of other actors on a devised piece and someone, while we were brainstorming, brought up this news story of this woman in Kansas who apparently had been living in her bathroom for two years. Her boyfriend had contacted the authorities, and they came in and intervened, and when they were questioning her, she [revealed] that every day when her boyfriend would ask her if she would come out, she’d answer — every day — with “Maybe tomorrow.”

And so, people kind of brushed it off and, you know, we moved on. But the idea stuck with me.

And obviously, it intrigued me because I thought it was a bizarre circumstance, but what really grabbed me, apart from the idea of loneliness and [exploring] the dangers of that situation, is the question of: “How would that relationship even work, or can it even?”

And then, actually, what gave rise to why this should be onstage, is that, just by serendipity, at the same time of [my internship], the Guthrie was also preparing for a production of Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days, which I was also set to be an assistant on that summer.

Looking at that play in terms of what Beckett has done — having a woman who is buried up to her waist in the Earth — also set me on a path and instilled me with a sense of “could this be done?”

So, the other thing that I often do with my writing is that I let an idea sit in the back of my mind for many (coughs) years... to a frustrating extent. But I put pen to paper in the summer of 2014, when I felt like I had thought about it enough to be able to activate it on stage, and it grew from there.

Chad Austin, Director: And then, the piece came into my orbit when I first took over [as] Abingdon [Artistic Director] at the end of 2018. Max had already premiered the piece at the Fringe Festival [where it won an Overall Excellence Award for Best Play], but I loved the piece and wrote Max and we started seriously talking about moving forward with a reading and the whole thing. And then, the pandemic happened.

So, obviously, programming changed for a variety of reasons, and after COVID, I felt the [subject of the] play was in poor taste — you know, the idea of “let’s not talk about isolation right away”… it was “too soon,” as they say. (Laughs). So, I waited a bit, [but] when I felt like enough time had passed and wanted to start the conversation about giving the piece its Off-Broadway premiere, I e-mailed Max out of the blue, and said, “hey, I’m still thinking about your play.” I was so grateful that he was open and excited about the idea.

Mondi: All I would say, especially after this conversation, is that it’s wild to think back to that first conversation in 2018… it doesn’t seem it, but it’s actually now such a long time ago… and I just want to say that theatre is such a weird industry, and plays take twists and turns in their weird journeys all the time… so I’m just so grateful and thankful that Chad has picked up this play and is taking it now on this wild journey once again.

Austin: And I’m glad that Max said “yes” to my offer... and now we get to produce this beautiful jewel of a piece.

Given Abingdon’s goals, and building upon the previous work presented within Abingdon, what makes the piece right for the company? And vice versa?

Austin: We’re continuously supporting new work and emerging artists. When I cemented our 32nd season, my goal for the year, in terms of work presented, was to make it the bravest season yet. And I think Max’s play is truly one of the bravest plays I’ve read, especially in the last few years. And it’s not the easiest of plays to get produced — it’s not the easiest conversation to have. To produce a new play based on a true-life event about a woman who is stuck to a toilet is quite a hill to climb, you know? (Laughs).

But I wanted to program this play because it stretches the imagination and moves the needle in terms of [defining] what theatre can be, and what part you play in the theatre as an audience member. I think Max’s work and the way he devised this play — how he challenges the idea of what is real and what is not real within this environment — is what audiences are looking for…. to get excited and have their minds blown by an outside of the box theatrical experience. And I think that’s what we are [at Abingdon]… that’s what we do. We’re very excited about leaning into intimate pieces that don’t have flying cars or pyrotechnics or things like that. Well... not that there’s anything wrong with that either.

I guess I would have hoped, for Max’s sake, there was another company also doing it, but I think it takes brave companies like Abingdon to support the work of this brilliant play that we may not have seen otherwise.

In what ways, if at all, have you relied on the real-life models to help you enhance this story and your process with it?

Mondi: When I first learned of this story, I looked up a news article from a local NBC affiliate. It was a very bare-bones police report… there were no names or anything like that – to this day, I don’t know the people’s actual names. I've done very little research into the story beyond some Googling. But I’ve allowed myself to be free and explore how that marriage might work – which is, as I said, what intrigued me [about pursuing it] in the first place. I got lost in the creation of my own theatrical world.

Austin: The same for me. I knew that Max had only read the story and nothing else. There’s not much history [beyond that] ‘cause I have looked, because, as we’re building this piece, I’ve, obviously, just gotten more curious. I wanted to know more, but I couldn’t find any follow-up [stories], but as far as the details that Max has expanded on, and as far as the story that he’s telling between these two fictional characters. I don’t know if I need much more because the story has [grown]… it’s so much different now from the original [source and news article].

And what about the story made it the right material for a stage piece?

Austin: I think anything that touches on any sort of topic that will engage conversation is such a fascinating way to do theatre. When I respond to people who have read the play — [those] whose reaction is like “WHATTT?! This is crazy!!” — I always like to remind them, it’s inspired by truth. It may seem crazy, but it’s really not. It’s based in truth. I lean into it a little bit more with that conversation, because I think with plays like Beckett’s Happy Days, as Max mentioned, you can also have a reaction [like], “What kind of woman is covered in sand?” It’s the same idea within this play… like you’d think “she can’t possibly be attached to the toilet.”

It’s just one of those weird and fascinating stories that makes your brain expand and challenges what is real and what’s… not, you know?

And I think, in [discussing] any sort of mental health [aspect] to the piece — without trying to put another layer on top of Max’s work — I will say, in a more general sense, that I think anything that touches on any sort of topic that will engage conversation is such a fascinating way to do theatre. That’s why I felt a calling to put it onstage.

Mondi: And what I was much more interested in — again, going back to creating my own world within the story — is not actually having her be crazy, like everyone assumes, but [answering the question:] “What if she’s a fully capable woman, who also happens to be the breadwinner of the family, mind you, and she’s actually doing this seemingly of her own volition?”

So, actually, as opposed to just judging this woman from what we think we know, what if we approached it with a little more curiosity as to [provide an answer to]: “why would somebody do this? What sort of life would they lead? How would it be better than the life they’re leading now?” Or at least having the curiosity to just ask the question in the first place.

Austin: What’s particularly interesting to me, to piggyback off what Max said earlier, is that with the version of the story presented in this play, my thought is that Gail is making this choice.

And I think that’s what makes it’s interesting and [offers up] the ability to people to make their own assumptions and choices. I think that’s the genius of Max and his writing…. I love that it’s not so clear. It’s constantly asking questions. You know, it’s asking you as an audience, do you believe that Benji [her son] exists? Do you believe that she sees you or doesn’t see you?

It’s all about your own choices… it’s up to you and your interpretation. And I think that will be so thrilling for audiences when they leave the show to take from it whatever they got. Which will be different for everyone. What you leave with [will be] totally based on your own thoughts and how you, singularly, feel about these characters. And I think that’s so cool.

Why, in your opinion, is it important that these types of stories be told? And why now?

Austin: I think people are constantly grappling with these [issues of] mental health... with how they move forward in life, and we still think, on a daily basis, “what is the impetus for putting two feet on the ground and getting out of bed in the morning?” If you even can. So, I think the idea of Gail’s pause room is universal among people who have challenges and just feel really stuck… regardless of the circumstances. Because even though it’s a choice, you know, literally and figuratively, Gail is stuck. And I certainly resonate with feeling stuck or isolated… or even feeling too afraid to break out of a box, or a “pause room,” so to speak. So, although putting a “mental health” [label] on it may be too aggressive, I think we’re all familiar with that fear and wanting to be in our own space.

And, I’ll mention, too, a lot of my angle or my approach for this play [surrounds] the erasure of Gail. Ultimately, that’s what’s happening in the play, is it not? She’s being erased. And that’s poignant because there’s a lot of global discussion in regard to women being erased in society right now. Not to mention, what part women and men play in work, life, business, and in growing a family. It’s all very resonant.

Mondi: The danger in isolation is that it’s actually a lot easier to be alone that it is to be around a lot of other people. As an example — and, granted, I’m not a singer or performer — but I would imagine it’s a lot easier to sing a song by yourself, alone, as opposed to singing in a large chorus, unified and in harmony. It takes more work, you know?

Of course, I wrote this play well before the pandemic occurred, but now, coming back to it with putting together this production, [those ideals] are much more relevant and in your face. There are just so many things in that regard that I find I’m definitely thinking more about.

What was revealed during the pandemic is [this concept] that if we can avoid an interaction with someone, we do. And, for example — I know this is silly, but I’ve been thinking about it a lot — during the pandemic, we were all instructed to do no-contact food delivery. And I’ve noticed, even though the lockdown is over and has been, that [option] still persists with a lot of people. It’s just a tiny, little interaction that you could have with someone — they’re literally handing you food — but some choose to have them leave it at our doorstep.

We’re just constantly removing interactions from our lives, and sure, it may actually make things easier in the moment, but I think overtime, it’ll be something that’s really going to corrode us.

Austin: That’s such a beautiful point. If I can add, just thinking about [other] ways our lives have changed, business meetings are now always on Zoom. I’ve had more meetings on Zoom than not, even when the pandemic [has been] over. We’re able to be in our individual space, possibly in pajamas if your camera is off… we didn’t have an option to “opt out” of an in-person meeting, in this way, before the pandemic. And we are kind of “opting out” more now…. The more I think about it, the more I see it. What a fascinating observation. Thanks for sharing.

Similarly, as you said, this production touches on sensitive topics related to mental health, such as isolation and pushing away or delaying life events because one might not be ready to deal with them. In keeping with the show’s focus on these issues – and given that the play is based on true events – what advice would you offer to someone who might be struggling with similar feelings?

Mondi: Ha! I’m going to make a point here ‘cause this is similar to an argument I’m currently having with my mom. She’s now retired and lives up in Maine, and I tell her, “You have to see people.” Like, you can’t just… stop.

I think, partly as a result of the pandemic, we have overvalued our pause rooms, if you will, and our safe spaces. And I think we have to find value in being uncomfortable again.

Obviously, in some cases, that’s easier said than done. But just get outside and look at something far away, as opposed to the wall in front of you. Like, take a walk. Spend time in nature. It’s as simple as that.

Austin: Get out of that comfort zone. You’ll be all the better for it.

Finally, what do you hope to instill in audiences as they come away from this play?

Austin: I’ll say that as broad as it is, I think this play has so much bravery tied into it. I think Gail is strangely brave in her choices. I think that certainly Ben is brave [insofar as] he is moving forward and able to be the father that he needs to be. There is so much of a human persistence within this play, so I hope that inspires people not only to see others for who they are and what they may be struggling with, and to maybe be a little more empathetic, but also to see the bravery [in] moving forward, getting two feet on the ground, and living the life [one] dreams of.

Mondi: A great question that gets asked of us within a lot of plays is: “What do we owe each other?”

When I started to come to terms with the idea of writing this piece, I couldn’t actually write it for a while because I couldn’t figure out what the engine was, or what it should be… you know, the [element] that [drives] the plot and the themes. And what made it all click for me was when I realized that Gail forms this relationship with the audience that Ben doesn’t have… and that’s really what makes it [whole], and makes it work as a full piece in a lot of ways. And I think that’s kind of [the crux], isn’t it?

And so, because I centered so much of my writing time around the audience, I found myself asking questions as they would: “What does Ben owe her? What does she owe Ben?”

But I think, through the course of the evening, we, as an audience, are [eventually] put in the position where we’re complicit with what’s going on. And I then found myself asking questions of them, too: “What do we owe her? What do we owe to each other?”

So, whether or not the audience has an answer, I hope that’s a question that comes up for them. But overall, I think, simply, that people are going to be in for something really special. I hope they’re surprised.

Maybe Tomorrow, produced by Abingdon Theatre Company, plays the Mezzanine Theater at A. R. T./New York Theatres (502 W. 53rd Street) through April 6, 2025. Austin will host a talkback about his directorial process following the performance on March 26; additional talkbacks, featuring Paige Bellenbaum of The Motherhood Center (focused on The Postpartum Experience) and representatives from the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) of New York State, will occur on March 27 and April 3, respectively. For tickets and/or more information, click here.