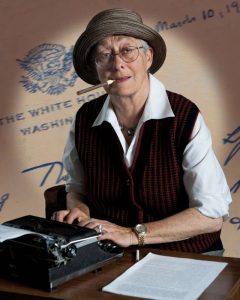

As Hick: A Love Story moves on to the FringeNYC Encore series, StageBuddy sits down with the star of the one-woman show and playwright, Terry Baum. Hick follows journalist Lorena Hickok and first lady Eleanor Roosevelt's romantic relationship, which began right as FDR became president. It highlights the struggles of concealing a lesbian relationship, the love Hick and Roosevelt had for each other, Hickok's career struggles and the tumultuous times of the Depression and WWII.

Where did you get your inspiration from and why did you decide to tell Eleanor and Hick’s story in a one-woman show?

Well, I was inspired by the first solo play about Hick, which was by my dear friend Pat Bond, who toured the country with it in the 1980s. At that point, her play was just based on one book, the biography of Lorena Hickok. I was doing a benefit for Pat Bond Memorial Old Dyke Award in San Francisco, which we created in her memory. I decided to do a scene from Hick. I got Pat’s script from the library and it had such a tremendous effect on the audience, this very short scene. I felt called to be Hick. I felt like I could do something different from Pat’s, because there was so much information out now and because I’m a playwright and she’s a storyteller. My inspiration really was doing the short scene and discovering how much it meant to people. I did a very short tour of South Africa and did the short scene there. I was absolutely amazed that at a college in Johannesburg, this story about the first lady of the United States was so powerful. I felt that doing it in a solo show kept it more easily from Hick’s perspective, because once you bring someone playing Eleanor onstage, you have a very different dynamic. I also wanted to have, at this point in the play, the actual voice of an actress playing Eleanor; the only thing you hear her saying is verbatim quotes from the letters that Eleanor actually wrote to Hick. I wanted to have that documentary evidence very, very clear in the play, so people can come to the play and decide for themselves whether they agree with me that Eleanor Roosevelt was in love with Lorena Hickok and had a sexual relationship with her.

I liked your use of the verbatim quotes.

I just wanted to point out that I had to get permission from the Roosevelt’s estate to use them. They’re not in the public domain. For anyone who feels like I’m outing Eleanor Roosevelt against her will, I can only say that Eleanor’s estate is behind me in doing this.

How much time—in terms of hours—would you say that you researched for the show?

Well I spent a whole week in Hyde Park at the FDR Presidential LIbrary studying the archive. So that was eight hours a day for five days. I think at one point I had counted up that I read 13 books; not all of them were books, some of them were quarterlies that had articles. But it’s difficult to say, really. It’s a lot of hours. But it’s been great. Actually, when I was in Hyde Park I talked to people who knew her and got a lot of insight from that. That was very interesting. So that was a week at Hyde Park, a few hundred hours I would say.

What do you want people to take away from the play?

I want people to understand that Eleanor Roosevelt, who was the greatest American woman of the 20th century in my opinion, was nurtured and mentored by another woman that she had a love relationship with and that this woman essentially gave up her own personal destiny in order to be there for Eleanor. Hick did, as I show in my play, quit her job. She was really on her way to winning a Pulitzer Prize someday, and she let that go for Eleanor. It’s a very hidden history of gay people, so much of our history is lost, but fortunately Hick and Eleanor wrote all of these letters to each other and Hick had the courage to donate them to the archives. But actually the first person who read the letters, Doris Faber, who wrote a biography of Hick, tried to convince the head of the library to burn them. Even then, there was a chance of losing everything, but the head of the library refused to do that. Another thing I think is really important is that famous historians are still denying that this relationship ever happened. Ken Burns, who did The Roosevelts: An Intimate History, he had Hick in there, but he completely ignored the romantic relationship between Hick and Eleanor, where he went into great depth into FDR’s liaisons. When he was challenged about that, he said that there’s no evidence that it happened. I mean, you heard those letters, it’s just clear that Eleanor was in love and they had a physical relationship. It’s pretty shocking that he couldn’t face up to it. Also Doris Kearns Goodwin, who won a Pulitzer Prize for her book No Ordinary Time, which is about the White House during the war years: Now, Eleanor asked Hick to live at the White House, but they were not lovers anymore. Goodwin explores that possibility and ends up denying it herself by using some quotes from Eleanor’s letters and leaving out the parts that made clear she was in love with Hick. I mean this is a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian. I think people need to know that and confront them on it. I think that’s part of why I’m doing the show, too.

I think that if people don’t think it’s clear from the language in the letters, they should look at the volumes of letters they sent back and forth. I would never write my female friends that much.

No, really, I love my friends dearly, but I don’t ‘ache to hold them close.’ I just don’t. There are so many things and there’s real smoking guns, when Eleanor’s talking about the scandal of her daughter’s divorce, she writes, ‘One cannot hide things in this world. How lucky that you are not a man.’ Now why would she say that? There’s only one reason. In other words, one can hide things if one is having a love affair with a woman, because people just can’t imagine it, so therefore it’s very lucky. I think it’s clear to an open, 21st-century mind, so these people are hung up on it. I think that’s important for people to realize that some of our history is still hidden. Eleanor is an absolutely amazing, courageous outspoken person. That’s another reason I’m doing the play is to make people think about Eleanor Roosevelt and quite frankly, even though Burns and Goodwin think that it besmirches her reputation to have it known that she had a lesbian relationship, I think the exact opposite is true, especially with young people now. Eleanor had this incredibly courage and desire to experience things that gave her the guts to do it.

What would you say the best and most difficult part about doing a one-woman show?

I’ve actually done a lot of solo shows, [though] this is my first biographical show. The best part was getting into Hick’s character and getting to know Lorena Hickok more, understanding what a great and compassionate person she was. The worst part of a solo show is the cast parties are a drag, but the truth is—that’s a joke. I’ve been supported by many people putting enormous energy into this project. I think a lot of times when you’re working by biography, sometimes when you get to know the person better, you don’t like them so much. That hasn’t happened at all with Hick. I just have great compassion for her and her struggles and I’m very excited for more people to know about her. That’s a big deal for me. She was also a pioneer in journalism. I mean in fact they do still study some of her columns in journalism schools. I ran into somebody who was in graduate school in journalism and she knew about Lorena Hickok.

To answer your question seriously about what’s the most difficult thing about a solo show, I have to say I’ve done quite a bit. It’s a muscle you build up. When I first started performing solo, it seemed very exhausting. Like my friend who finally did a solo show, who’s a very experienced actress, she said, “Oh my god, it’s horrible! When you’re not talking, nobody’s saying anything.” It’s hard for me to think of something negative about it. I really love representing Eleanor and creating that whole reality.

How did you decide when the transitions would come and the order of the scenes?

It’s the dramaturg Carolyn Myers who I worked with the most on that. Adele [Prandini] came in recently to direct the version we brought to New York, but we already had two runs in San Francisco who were directed by Carolyn. She’s really my theatrical partner. Of course, many, many scenes were written, memorized, perfected and rehearsed and then thrown out, which is the extremely irritating part of the creative process. You really regret spending all those hours memorizing something. We had several threads: of course the relationship between Hick and Eleanor, the second was work and the conflict that was created by her relationship with Eleanor, and the third was what was going on in the country in that time. It was balancing those things out. The audience’s primary interest is in the romance, but we want people to understand the tumultuous times they were living in and also Hick’s struggles in her career. In fact, the writing she did after she quit being a reporter, when she started working for the New Deal, traveling all over the country writing reports -- she did that for three and a half years -- those reports are considered the most complete description of the Great Depression by historians. So that is a tremendous body of knowledge she created and some of the writing is absolutely incredible. The description of people’s stories; there’s a description of this dust storm she experienced and we really wanted to somehow get that in there. You know when you write you have to kill your darlings, that’s what they say. We also wanted to focus on Hick’s decision to donate the letters. We really felt like that was really the conclusion of the play -- the struggle of whether to come out in the future. In fact when she donated the letters, it was with the provision that they could not be opened until 10 years after her death. So it wasn’t that she was really to come out right when she died, which was perhaps very wise of her in retrospect. That moment of deciding seemed very important to me.

Is there anything you’d like to add?

I found the response of the New York audience to be very passionate and fervent even. I did live in New York City at various times, the last time from ‘96 to ‘99. There is a love of theatre here that goes beyond what exists in San Francisco. Even though we were very successful in San Francisco, it is wonderful to have the feeling of that kind of intense focus from every person in the audience. That seems more than I got in other places. I really appreciate that. I’m not surprised at all, because I was hoping for that.