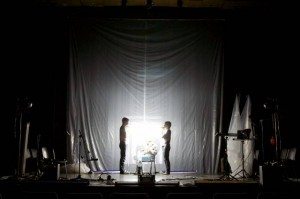

What is the role of mythology in theater? What is the role of the document, of the act of witnessing? How can the two combine to reach the deeper personal and artistic truths in a time and place of crisis, and what happens when that place is both your home and a place in which you feel foreign? Playwright and director Rubén Polendo and his company, Theater Mitu, collaborated in the creation Juárez: A Documentary Mythology, now playing at Rattlestick Theater. We talked to him about his work, his process, and the idea of approaching and representing a home you struggle to recognize.

What is the role of mythology in theater? What is the role of the document, of the act of witnessing? How can the two combine to reach the deeper personal and artistic truths in a time and place of crisis, and what happens when that place is both your home and a place in which you feel foreign? Playwright and director Rubén Polendo and his company, Theater Mitu, collaborated in the creation Juárez: A Documentary Mythology, now playing at Rattlestick Theater. We talked to him about his work, his process, and the idea of approaching and representing a home you struggle to recognize.

Hi! So I just want to say first off, I really, really enjoyed Juárez . I think it was really something important, and unique, and it was just really impressive.

Thank you so much, that’s very kind. Thank you.

I just had a couple of questions that I wanted to start out with. On a basic level, can you sort of speak to how you came to documentary theater, and the idea of a documentary mythology?

Sure. In terms of the work, Theater Mitu is really invested in several key tenets. One is the idea of really having a global conversation, and figuring out how, as artists, we navigate cultural territories. Those can be political, they can be geographical, they can be mythological. The other thing that is hugely important is not only the investment in the theatrical, but in what one could call the hyper-theatrical. It’s a way of seeing our world. I love the criticism that it’s just a lot coming at you, right? That it’s kind of a rapid-fire experience. Our company, we have this event on a yearly base in the summer, something we call an “incubator” -- it’s a space for us as a company to come together as a group of artists, and really speak to what the things that are really disturbing us. I don’t use the word “disturbing” in the horrific sense, I mean what’s placing us out of our comfort zone, what keeps you up at night, what, as an artist, is just nagging at your shoulder. This could be quite serious, it could be -- again, a range of vocabularies.

I came to my company after having had a visit to my parents’ home, to my family’s home in Juárez , and realized that the place felt foreign to me. Not only geographically, but in terms of the hearts and souls of people who are very dear to me had, over the past decade plus, really been transformed by something I had no experience of. I mean, hearing and seeing everything from nieces and nephews to friends and family and how they navigated that really both inspired me because they’re so strong, and also broke my heart because it was so challenging on every level. I left really altered. Ironically enough, it wasn’t at the height of all this violence that it happened. It’s actually that it was a moment of what I’ll call survival, with people trying to just survive and bring things back to life.

So I spoke to the company, and it’s very strange, because usually as an artist and a director my vision of the work is very cohesive, they’ll be a kernel and I can really see and feel and almost sink my teeth into where we’re headed...but I brought this to the company in a way quite nude as an idea, which is to say, I sat there and said “I know that I don’t want to script something.” There’s a protective nature in me which wants to not have Juárez be a metaphor. I don’t want it to be something that’s symbolic of something else. I have very particular standards for me, as an artist of color in the United States, for the performativity of race and cultures. It’s like a minefield--

Oh, yeah, definitely.

[Laughs.] So I sat with the company, and the last part of the answer is that it became very important to me to figure two things out. What was our role, if any, in that situation, and the only way we could figure that out is really taking the company there as foreigners, as I was. The second was, what would be the language of the stage? It became clear to us that the voices on the stage would be those of the people, and our role would be one of witnessing, not of reenacting, not of commiserating. And so that’s where we landed. We had never investigated documentary theater or interview.

So this is the first time for you with documentary theater?

Yeah.

Oh wow, I had no idea!

Yeah! It’s the first time. I have great friends and mentors who work with documentary theater and interview and I have great respect for that, and had a history of being surrounded by that, but not of working directly with it in this way. So we had this further kind of beautiful challenge: how do we investigate the question of documentary theater? And how do we then really keep to Theater Mitu’s investment in hyper-theatricality? How do we take that text and honor but also theatricalize it? How do we engage all the puzzle and magic and mystery and kind of beauty to it? So that sort of sent us on our journey.

Wow. That sounds like a real adventure! So going back to a previous point, something that came up to me is how central the issue of race is when it comes to the Juárez /El Paso divide, first of all, and then also when it comes to the fact of an American audience, and the fact of the automatic sort of othering that goes on with many Americans when it comes to Mexicans, especially Mexicans in Mexico. As far as I understand it, the other members of Theater Mitu are not Mexican?

Yes. There are two actresses in the performance of Latina descent, but the core of the company is absolutely not Mexican.

So how did you navigate the issue of white actors embodying Latino and Latina voices? It seemed that one of the central ways that you approached that was by emphasizing the role of witness, with the ear pieces, and with the very obvious centrality of the fact that “I’m not this person, but I’m hearing this person.” Was there a struggle with how to approach that or how to represent that?

There was. I love your use of a few terms, one of the term being “otherness”, and I’ll come back to that in a moment, but the other being “struggle.” Which is to go through the heat. Going back to a part of your first question that I didn’t address is, how do we arrive at this word “mythology”? So clearly the documentary part is key. When we started out on this project, all of our sensors were really awake to the question of race. This has always been a central question of my work, but I truly believe that there’s a big problem when as an artist I’m told that I “can’t” do something, so my reaction is, as an ethical, hopefully moral creature, the question is actually how can we do it? There’s a way to navigate all those channels. Not to be like, “Oh, that? Can’t do that, it’s off the table.” There is a space for that, and that to me is a theatrical space.

When we went to Juárez , we asked that question repeatedly. And this is going to contradict my own views in many ways, but everybody looked at us like, “Are you crazy?” They looked at us as if to say, like, people are dying. It sounds like such a bourgeois concern, to then be like, “Wait, should we be allowed to tell people about this?”, and the people were like, “I don’t care.” One of the people said, “I don’t care if you’re from fucking Mars. Just bring these stories out to the world.” And I was like, “Oh, got it.” I say that because it didn’t absolve us, the company, from any responsibility. And it’s like, they’re actors, they’ve repeated this piece enough, for a year that truly they could do it without any of the tools -- without the cards or computers or whatever -- but the idea to me is that they’re actually markers which has to do with a kind of attestation. They hear the interview or they see the transcription of the interview, and it actually calls them away from the instinct to fully perform a kind of character. And so what you see is a little of that tension, right? It’s less about, “Oh look, they don’t know their lines, they’re just kidding around”, and more about the ghosting of the person, of the interview, of the transcription. The idea is the constant reminder that this is not your voice, this is not your language--

That’s a great phrase, by the way. I love that phrase “ghosting”. That’s beautiful.

But that’s really what’s going on! Because it removes us from the story, but really it moves us toward the story, because you’re hearing these people. Now, the interesting thing is that some of those words are actually my father’s words. One of the actors, Mark, has several speeches that are my father’s. And all of the sudden, to hear my father acted, I was like, “Yeah, stop, no! That’s freaking me out right now!” [Laughs.]

There’s such a trust in the company that it feels like, there’s not even a need to justify yourself. It’s just like, yeah, great, so let’s navigate, what about this, what about that, yeah, okay. And then we begin to find those ground rules. So the hope is that these markers really allow the performance to transmit. And there are these instances where people will tell me things, and I’ll think “Oh, there are these beautiful monologues he used, but I wish it were more dramatic”. And then I’m like, wait, this person didn’t script a monologue, they were speaking their story. Another thing is, when people truly speak to you about tragedy, because they’re surviving in it, they don’t really release the drama of it. People are telling us of their everyday lives. So it’s not a monologue where they’re saying, [dramatic voice] “I remember.” They’ll tell us about a terrible thing, like, “Okay, this happened”, followed by, “and then the next day I walked my kids to school.” That’s what has to happen. So in a way there’s an honor of that kind of part of it, the archiving and documentation, and I think that creates a kind of conversational style, a more journalistic theatricalization. And going back to the word mythology, the mythology for us really became when people said, “At this moment, the crisis is such that it actually transcends.” The race is important, these ideas of culture are important, but it’s not transcended. And so it really becomes a narrative that has to do with violence, and corruption, and fear, and family, and hope, and those things aren’t Mexican. So that liberated us. There are still moments when I watch the show and think, “Yeah, okay! We can still mess with that!” So it’s really alive, I think, in our creation process.

That’s beautiful! So, one thing that I was very curious about is, especially as I was hearing narratives that varied so drastically, narratives from older people who remember what Juárez used to be, narratives from younger people who are angry that it’s not the way they want it to be, and narratives from people who were even approaching you differently (I’m thinking specifically about the angry journalist here)--

[Laughs.]

Who seemed just not to be super pleased with the interview itself--how did it all work? How did people react to you just asking them to speak about their experiences?

Well, first as a little footnote, one of the most giving interviews was with that journalist, who was awesome and really ferocious, as you can tell. I have to say, I continued to be surprised at peoples’ willingness to share their stories. With the company we created a rubric around our investigation. First and foremost was the idea of not manipulating the interview toward crisis. In other words, not to come up to people and say, “Tell me why your life is so terrible”, but to actually really invite people to tell us of their day to day lives, and to tell us what they remember. What is their fondest memory? When was the first time they remember crossing a border? These really panoramic questions that allow people to answer concretely, to answer poetically, to answer darkly, to answer lightly. And it really, I think, invited people to not feel dissected. One of the biggest problems in Juárez is that journalists descended on the place, and really created a series of headlines. And I think the populations of Juárez and El Paso really felt like, “We’re not just a headline.” Yes, there’s a crisis, but there’s a lot more to that story. And they were very eager to tell the non-headline, all the other things going on. Those can be dark, but they’re not sexy. So the idea is that “Man Gets Kidnapped” (which is such a gross word to apply to a crisis, but anyway), “Man Gets Kidnapped and Dies Horrifically.” But sometimes it’s like, “Man Gets Kidnapped and Has To Return To His Daily Life.” And how the fuck do you do that? To me, that’s really moving because that’s not a news story. That’s actually a human life. So we really kind of opened that door and people jumped in.

Now, what was interesting to me is, going back to your point of otherness, is that there’s this incredible divide presently on the border between El Paso and Juárez. Not ethnically, really, but purely citizenship wise. In El Paso, you have this identification as “American”, which actually means, for around 80% of the population, Mexican-American, and then of course you have the Mexican population on the Juárez side. On the El Paso side, there was such a resistance to discuss it. There’s almost this sort of conscious sense of “it’s better not to talk about it.” Not out of fear, just out of “what could be wrong?” On the Juárez side, there is this kind of exhaustion about talking about it. And so when we would say “Tell me what happened”, you know, about the violence and stuff, people were like “Really? We’re gunna talk about this again?” But when people were invited to talk about larger, more emotional questions, it felt to me that people landed on details or moments or memories that they haven’t sat in or visited, and I was just so moved. It’s also that there’s not an incredibly thriving theatrical ecosystem in the city, so we were saying “we’re doing a documentary piece”, and everybody looks at you like, “what? A documentary movie?” So it really took awhile to develop a relationship, and to introduce what we were trying to do, and to earn that trust. I think that’s why we really incubated on the piece for quite awhile in terms of returning to the place and gathering those interviews.

I’d like to speak for a second about the idea of mythologizing a document, the idea of documentary mythology. I was really taken by that phrase and think it speaks to the purpose of documentary theater, as opposed to other types of documentary and other types of recording fact.

Sure. For us as a company, the title of a piece is often a marker for our goal. So we often find ourselves with these very convoluted, clunky titles. That just became our kind of research rubric in a way. In this case, it’s really the use of the word “mythology” in a kind of Joseph Campbell-esque way. Campbell held the idea of mythology as one of two things: the stories we tell to survive, and/or the stories we tell to make sense of the world around us. So what happens is, when one goes into a documenting, an interviewing and a photographing and such, for me it really becomes important as an artist to not only have that archive, but to really create a united orientation or a compass with which to search that archive. So it really became about finding a plurality of voices that are actually telling the stories they need to survive, and the stories they use to make sense of things, which can also have mystery. It was interesting to then travel through -- I mean, we have hundreds of hours of incredibly moving, funny, strange, odd, heartbreaking, inspiring interviews. So it becomes this incredible challenge to, in a way, curate the piece. And there was a moment where the piece was really going to veer into the narrative of my father, who’s 85, who’s seen the entire span of Juárez, but then we made a choice that a plurality of voices was really, really important. This includes voices that I disagree with vehemently, that make my skin crawl. There’s a gentleman who speaks about “nothing but the worst of the worst can come out of this.” Literally in that interview, I was about to go crazy on this guy, but I had to step back and be like “archive this and remember that feeling. Remember how cold that office felt and how bright the light on me felt, and then bring it back to the States.” That’s the story that he tells to make sense of the world around him.

What’s tricky is that the pedestrian use of the word mythology has an element that it’s not true, or that it’s exaggerated or something. We’re really veering away from that. It really is just the stories we tell, and our job was to really find the motifs. As we navigated through the archive, memory kept coming up in a way that was really unexpected to us. It was almost as if we had prompted people to say, “Tell me your memory”, but people brought it up immediately. People talk about it all the time in Juárez. People eat at a taco place and say “Oh, remember when it was blah blah blah here?” It’s such a survival mechanism. You realize that memory is so tethered to hope, and you pass on memories to kids, and again, memory became a kind of orienter for us.

Definitely. I think the Campbellian notion of myth is central to all theater, but perhaps more so when it comes to documentary theater, simply because you are representing a truth. To use the word mythology to represent truth hints at the deeper meaning you were trying to find, to get at “the real stuff.”

Yeah, that’s such a beautiful read of that. I would argue that when you see a documentary theater piece, and it’s really, really successful, they have done that. They have found that kernel of mythology. That heartbeat that’s making sense. So for us it was really a calling, to say “Don’t forget that this is what you’re doing. Don’t get seduced by the newest headlines, but rather, get into the heart of that belief system.”

So I have a few last questions, which are about the writing process and the creative process. So, the idea of the play, it was developed collaboratively?

That’s right.

And was it written collaboratively as well, script-wise?

Yeah. There’s a mode of work which we do. We work with a device called “autonomous installations”, which is to say we create an orientation, a mythology that is based on the themes that came up: dreams, memory, change, violence, all of these things. That oriented us through the text. And then together we really pulled from the archive and created a palate in the room, of things that were to be used, to be played with, to be realized, and so forth. So what happens is, it becomes a laboratory. It becomes a truly democratic space. Every artist really takes on this commissioning of a completely autonomous installation. Which is to say, something which can stand alone. It’s got text and reflections on aesthetics, and they direct it, create it, shape it, and so forth. Then we create this sub-archive, which is all of this work, this inventory, and we then sit together and begin to curate this work.

Ultimately, my role becomes curatorial. It’s closer to commissioning seven artists to do these installations based on a gathering of research, and then I proceed to curate it and hopefully have some kind of cohesive arc, and then of course direct the performative aspect of it. It’s actually incredibly authored as a collaboration, but it’s not the sort of collaboration where we sit together and all say “let’s do that.” One of the actors or one of the designers will actually take over and say “this is what will happen”, and everyone is working in the service of that installation...but in a second it all reverses, and someone else takes over. There is a kind of lead in each of those installations. And then the challenge becomes, like, some pieces were left out because it was impossible to cohese them to something else. I think that’s what creates this sort of density. So, in essence we are rushing you through a kind of gallery installation. In fact, there’s a grouping of another series of installations that we felt really compelled to include but couldn’t that are actually part of a gallery installation. When we showed the piece in Juárez, we actually showed those other installations in a gallery in El Paso. It was really awesome to have people view both of it’s dynamics. Some of the installation work is in the realm of installation truly with video, some of it is performance based, but it’s not temporal, so it lasts forever. It gets pretty dynamic in that sense. We recently received the NICA grant, which supports the mapping out of a tour, and some of the places which we’re hoping to go to will support -- which we wanted to do in New York but were not able to -- the performance, as well as the gallery installations.

Oh wow! That’s fantastic!

Yeah! There’s a way that each of those images, even though they’re linked, have their own stand-alone grammar. So it’s a way of investigating that. But yeah, the authorship is really united, and I think that addresses some of the training the company does in our unified research, and in our history as collaborators.

That’s really fantastic. It seems quite unique, and it really seems to pay off.

Thank you!

Juárez: A Documentary Mythology continues its run at the Rattlestick Playwrights Theater through October 5. For more information and tickets, visit https://www.rattlestick.org/theatermitu/

Juarez: A Documentary Mythology continues its run at the Rattlestick Playwrights Theater through October 5.