Walking in on Harry Feiner’s set for Rocket to the Moon, Clifford Odets’ rarely performed 1938 play now receiving a revival at the Theatre at St. Clements, is almost like walking into the Kansas of The Wizard of Oz. True, the rural Kansas of that film is nothing like the sweltering Manhattan summer of Clifford Odet’s 1938 play. However, Mr. Feiner has depicted the waiting room of a Depression-era dental suite in similarly sepia tones. It is sparsely adorned with a few wooden chairs, a secretary’s desk, a coat-rack, and a set of windows looking onto a gloomy Manhattan street. Along the windowsill sit wilted plants which are still watered on a regular basis.

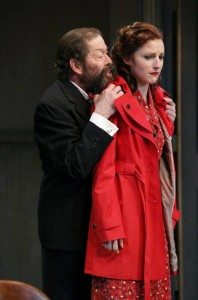

This suite belongs to Ben Stark, D.D.S. (Ned Eisenberg). He shares it with fellow dentists Phil Cooper (Larry Bull) and Walter “Frenchy” Jensen (Michael Keyloun). Occasional droppers-by include his authoritative and controlling wife Belle Stark (Marilyn Matarrese), her wealthy father Mr. Prince (Jonathan Hadary), and choreographer Mr. Willie Wax (Lou Liberatore). Last, but absolutely not least, is his young and pretty secretary Cleo Singer (Katie McClellan). Throughout the play, she brings in flowers in an attempt to lighten up the room, in contrast to the wilting flowers by the window.

This symbolism extends to her interactions with Ben. Ben feels that his existence as a dentist is meaningless, having fallen into a routine of bickering over money with his wife. Cleo is in a similar situation: An aspiring dancer, she lives with eight of her family members in one apartment on Madison Avenue. In spite of her family’s disapproval, she refuses to sacrifice her dreams. “I’m talented,” she proclaims to Ben at one point. “I don’t know for what, but it makes me want to dance in my bones!” Her passion awakens Ben to the possibility of a “whole full world, with all the trimmings”, and the two start a romantic affair. Unfortunately, like the gloomy Manhattan streets that the office windows look out on, apathetic reality is always waiting just outside the door. In addition to the possibility of Belle discovering her husband’s infidelities, the exceedingly wealthy Mr. Prince and the philandering Mr. Willie Wax have expressed interest in Cleo as well.

Director Dan Wackerman skillfully renders the style of the play. It clips along nicely, only flagging slightly during the play’s ponderous third act (there is one intermission between the two scenes in Act Two). What he hasn’t done, however, is convince us that the characters are genuine people. Some of the cast, especially the leads, feel like they’re playing at the period more than living in it. It doesn’t help that Odets’ playwriting, though imbued with force and passion, occasionally feels like a mouthpiece for his views and philosophy. A member of the Communist Party and a strong advocate for the working class, Odets wrote his plays (which include Waiting for Lefty, Awake and Sing, and Golden Boy) to generate social change more so than to entertain. His sympathies lay with men such as Dr. Cooper, who considers donating his blood for money in order to pay for his share of the office suite. Odets implores us to consider these men, who must give up their blood (both literally and metaphorically) to get by in this world.

That being said, the play is watchable, and the supporting cast is strong. Jonathan Hadary is by turns sleek and sympathetic as a fast-talking older man who sees Cleo as his last chance for happiness in life. Larry Bull’s Cooper is appropriately edgy and tense, and his breakdown towards the end of the first act is heartfelt and sympathetic.

Plays that rarely get done tend to have a stigma of being dated and irrelevant. Therefore, it’s something of a miracle how undated this play feels. As didactic as Odets could be, he certainly understood the anxiety of unfulfilled potential, a theme that is still relevant today. Wackerman’s production, while not entirely involving, provides a blessing for fans of Odets, who will get a chance to see a rarely-performed Odets play on a professional scale.