Experimental theater has a language of its own. If you’re just learning to speak it, it can be jarring or it can be refreshing. But it is no longer a new language, so those accustomed to it by now will recognize all of the same words and phrases they’ve heard many times before.

Like much of downtown theater, Trail of Tears, now at the Nuyorican Poets Café, speaks experimental theater fluently. Co-produced by Rebel Theater Company and The Eagle Project, it combines all of its familiar elements to tell a tale it regards as unfamiliar: the history of The Native American Removal Act. And its use of experimental theater tradition works to highlight the surreal silence surrounding this genocide – but only some of the time.

Most Americans will remember the basic story of the Trail of Tears as a passing note in their American history textbooks. Playwright Thomas J. Soto and the theater artists who interpret his work clearly recognize the tragedy of minimizing this horrid history; not only is the piece dedicated to shining light on this past, but it hopes to illuminate details and narratives unknown to its audiences.

Different forms and styles are used to present these narratives, but unfortunately the tone of the piece gets in the way of the importance of its content. There is a screeching dreariness that invades so much of the play, which is set inside such a small space that it becomes grating, even redundant at times. There is an attempt at injecting the play with wry humor in spots, but these instances are so infrequent that they get lost in obscurity.

This is not to say that the play doesn’t present some fascinating stories and details. For the most part, Trail of Tears works best when it connects the genocide of its title to the continued oppression faced by Native Americans in more recent years. It mentions AIM – the American Indian Movement – and the tribulations of those living in reservations on barren land.

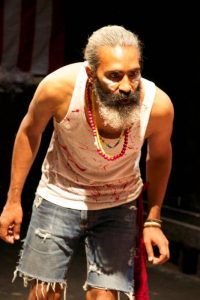

The piece is bookended with grass dance performances by Sheldon Raymore, a man whose movement is so light and free that it can appear completely improvised and true (despite the incredible amount of technique that is obviously involved). Raymore dances while an audio recording plays, describing his own struggle as a gay Cheyenne man who has dealt with bigotry and ignorance but has managed to persevere – a personal narrative that reflects the collective story of Native American history that the play means to convey.

There is a single moment of direct audience interaction (despite the director’s announcement that there would be no fourth wall present during the performance). One of the actors describes the idea that the last stage of genocide is standing back from the people who have been reduced to almost nothing. At that moment, the whole front row is approached by the many performers onstage, each audience member grabbed and confronted with the line: “Look at what they’re doing to themselves.” It is an uncomfortable and effective moment – the audience is being antagonized and condescended to in a gesture that symbolizes not only the experience of Native Americans in this country, but all of the people who have been subjected to ethnic violence since the beginning of time.