A poem by Leigh Hunt, at the center of Anna Ziegler's Boy, brings up one of the playwright’s recurring themes: the passing of time and the seemingly fruitless endeavor that is remembering,

“Jenny kiss’d me when we met

Jumping from the chair she sat in;

Time, you thief, who love to get

Sweets into your list, put that in!”

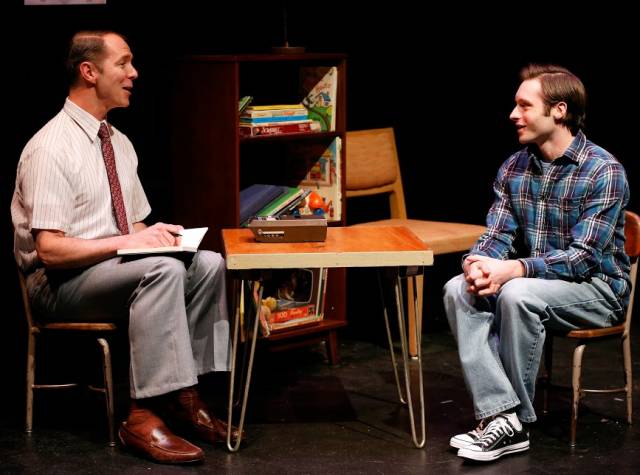

As in A Delicate Ship, her stunning memory exercise produced by The Playwrights Realm in the fall of 2015, Boy, making its world premiere in a production by The Keen Company, showcases Ziegler’s ability to build symphonies out of time travel, which she has mastered better than many science fiction experts. But the journeys in her works don’t owe themselves to complex machinery and advanced technology, instead they happen thanks to our emotional need to recall, to try to figure out the missing pieces that make up the puzzle of existence. The first time we listen to the poem in Boy, it comes courtesy of Dr. Wendell Barnes (Paul Niebanck) who is sharing it with the young Samantha (played by Bobby Steggert) who sees it hanging from his office wall. When the inquisitive little girl asks why he has it there, the doctor explains “I put it on my wall because I couldn’t forget about it”.

One wonders if Ziegler put the poem in her play, because she couldn’t forget it too...but regardless of that, the plot she has built around it is fascinating. The poet Hunt was at one point very good friends with Shelley, the Romantic writer whose second wife Mary wrote Frankenstein, from which Ziegler borrows several themes in Boy. It turns out that Samantha was born Samuel - his twin brother Stephen is mentioned but never seen - but lost his penis as a baby due to a medical accident, forcing his parents, Heidi (Heidi Armbruster) and Doug (Ted Koch), to try and find ways to give their child a “normal” life. When they hear of Dr. Wendell, who specializes in helping transgendered people and hermaphrodites transition smoothly into one gender, they realize that with surgery, hormones and therapy they might be able to raise a healthy daughter. Therefore they put their trust into this scientist who has been accused of being nothing if not a modern Dr. Frankenstein in the media.

The play is then divided into scenes that travel back and forth in a time frame that spans from 1968 to 1990, as we see Samantha meet with Dr. Wendell, and later as a grown man who goes by the name Adam. In “newer” scenes, Adam is courting a young woman called Jenny (Rebecca Rittenhouse) who likes him, but can’t put the finger on why he refuses to sleep with her, and is so precious about his childhood memories. There is nary an element of sensationalizing in Boy, as it’s completely uninterested in the details of why and how certain decisions were made, as it becomes more obsessed with the idea of creation, and how our memories can be precisely our greatest, and also most dangerous asset, in this process.

Steggert’s extraordinary performance as Adam/Samantha calls attention to itself precisely because of how unmannered it is. Seeing a grown man play a six-year-old girl onstage, would most likely make one expect big movements and loud or cutesy remarks, instead Steggert plays her almost like a flower bud opening up to the sunlight of knowledge. The more she learns about the world, the “bigger” the performance gets, as we see Steggert use his eyes and expressive forehead to show Samantha’s discovery of the world. It’s a beauty to see how in an almost inverse reflection, in “modern” scenes, Adam has almost completely turned inwards. This theme is represented by Sandra Goldmark’s intelligent scenic design which features an almost exact replica of the set we see on the stage floor, hanging from the ceiling.

As with the other plays in Ms. Ziegler’s resume, there is a sense of approachable intellectualism in Boy, that allows it to work both as conventional theatrical entertainment, but also as a souvenir that haunts you for many days to come. In Boy, this sense of the metaphysical comes through the theme of reflection, since afterwards we wonder if the play varies depending on whether you think of it as the story of Adam/Samantha or rather the story of Dr. Wendell. Is this the story of Dr. Frankenstein or his creation? Yet another element replicated from Shelley’s classic novel, since as popular culture has proved, few people now remember Frankenstein was the name of the doctor, not the monster.

Perhaps what Ziegler is asking then, is if the creation can ever truly be completely removed from its creator? And as we think about this yet another clue comes to mind, in the indirect mention of Milton’s Paradise Lost, a poem beloved by Dr. Wendell, which happens to be about the fall of man and expulsion from the Garden of Eden. After all, didn’t Samantha choose to be called Adam when she too was expelled from the garden? Yet, the writer shows compassion for her creations and her audience, because by the time we listen to Hunt’s poem once more, it’s the second half that’s more resonant:

“Say I’m weary, say I’m sad,

Say that health and wealth have miss’d me,

Say I’m growing old, but add,

Jenny kiss’d me.”

Remembering, after all, might be fruitless as means to the end of repairing or restoring, but as a connection to the process of creation and producing hope, it’s our memories that allow us to be both the makers and their art.