The first of three evenings of short works presented by Ensemble Studio Theatre is something the theatre could use more of. Running for 35 years, it's plain to see why the Marathon has such great legs: if variety is the spice of life, EST's given us a spice rack that seasons to taste. Quality and curation is the theme. That and, as one of Series A's playwrights, Mariah MacCarthy, suggested to me earlier this week in an interview, "people struggling to reach each other." Why not both?

The night opens with something new for the Marathon: a one-act musical, I Battled Lenny Ross, about the titular child prodigy and quiz show contestant who, at twelve-years old, won $164,000 for answering questions about the stock market. In 1957 he was interviewed by Mike Wallace (Aaron Serotsky, who plays it both real and to the hilt with an impressive baritone), and that event is the springboard for the musical. As the interview progresses we're treated to lyrically clever and tuneful ditties by lyricist and composer Matt Schatz, which shine a light on Lenny's home and dating life (Olli Haaskivin and Julie Fitzpatrick are wonderful -- and do most of the singing -- in the factotum roles of Man and Woman presenting his parents, a fellow contestant on a quiz show and his would-be fiancée). It's soon made clear that Lenny (Jake Kitchin in a precocious performance) understands and is able to connect to facts and figures more than people -- whereas Wallace has always been a study of the latter. At one point Ross says to the suggestion of juggling his interests with having companionship "the more you hold in your hands the more likely you are to drop something." I won't reveal how, but the words prove prophetic. Daniella Topol's direction underscores the point with a break (with the help of designer Greg MacPherson's lights) that jars us out of time and into Wallace's head. The at-times lyrical book (by Anna Ziegler) works in perfect complement to Schatz's compositions. It's an early collaboration between the two talents and made me want more.

Second on the bill is Chiara Atik's 52nd To Bowery To Cobble Hill, In Brooklyn directed with millennial-centric specificity by Adrienne Campbell-Holt. The title refers to the destinations of two acquaintances who grab the same cab after a friend's engagement party. App developer Alison (a wonderful, vocal-fry-up-to-eleven Molly Carden) and grad student Halle (Megan Tusing, who imbues every moment with her understated annoyance) don't exactly get on. But it's news to Alison. After some rude (but one gets the sense, true) intimations about Halle's feelings for their spoken-for host, she throws caution to the wind and after years of passive aggresiveness tells Alison how she really feels. It quickly induces nausea. Alison does her level best to quell it with a story of a particularly traumatic show and tell that ends up humanizing a type that can all too easily fall into stock, though ultimately may not do much for Halle's view of her. The cramped quarters of a cab make for a claustrophobic ride, and anyone who's ever had to deal with one of those on-board TVs full blast can speak to the reality of Atik's playlet.

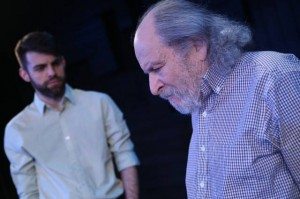

Amy Fox's Silver Men is a lyrical meditation on masculinity. Willis (David Margulies, who should play everyone's grandfather) laments his son's obsession with the color pink. His grandson, Matthew (an understated Tommy Helleringer), recalls his trip back from college to see the pink paint job on the barn (done by his own dad) in which his father described the serenity he felt when the sun was reflected by the snow and colored the world pink. For both men, young and old, who begin in monologue and meet in the middle at the middle man's funeral, this seems to mean he was gay. "Strange times," is Willis's refrain. Willis is an army man who learned how to be a man training in Mississippi. It's also where he learned that the sound of a bullet firing is the last sound you hear. First is the sound of it in motion, then hitting something and then firing. This fractured and disjunctive sequence informs not only the play's structure but also the order in which the men in this family passed on -- and also, how they pass on their memories, which themselves shift through generations. When the mother, Marjorie (a play-stealing turn by Catherine Curtain), comes out with her telling of the Pink Revolution, she experiences, by moonlight, a world colored silver. The play seems to list off the tracks at times, too loaded down by metaphors, but in the end, it works. "A barn shouldn't surprise people," Willis says (and you could easily substitute in son), but I'm glad this play, helmed by director Matt Dickson, did, managing to fit so many moving parts into a satisfying catharsis.

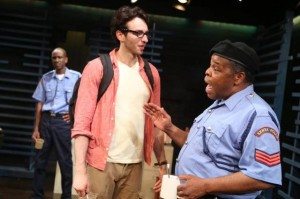

Will Snider's The Big Man moves the already fraught world of bureaucracy and parking violations to East Africa. A young (white) American (Gianmarco Soresi as a flustered and put-upon Gabe) goes to recover his truck from two Kenyan policemen who tied it down for being in the way of the President's motorcade. Director Matt Penn starts off light, leaving room for Snider's breezy patter with the two cops (the perfect Brian D. Coats and Ray Anthony Thomas), but the play turns a quick corner when Gabe appeals to their sense of shame. The misinformed Western, white perspective does not get treated with kid gloves here. Gabe, who in fairness has been living and working with an NGO for five years, is still an armchair general. He may speak of the injustices and the crookedness of the system, but one senses he feels most vividly about how he, a foreigner, might be taken advantage of. When he charges that these cops are not just susceptible to kickbacks but complicit in the murder of their own people, a pantomime of post-election riots plays out that leaves us (and him) humbled and a bit gobsmacked by the reality of the men he's accused.

Until She Claws Her Way Out by Mariah MacCarthy is about a ballerina, Elissa (played and danced by Naomi Kakuk -- who I reckon is a triple threat, though we don't hear her sing), who finds herself ensnared and (at first) enraptured with a fellow dancer in her company, Max (Kit Treece). When the relationship becomes addictive, and begins to sour Elissa's focus, she calls it off to land the lead in Swan Lake. Max isn't having it. In monologue, Elissa gives us the tumult of events -- the rationales, the wistful missing, the denial, delusion, the self-blaming, the outside-blaming and all taxonomies of blame, guilt and shame that spring from a complicated abusive relationship. The speech plays out almost like a dance and ends with an actual one when Max enters the scene for their duet which is passionate and scary, when the violent reality threatens to burst out of the neat and sensual choreography by director-choreographer Sidney Erik Wright.

If this first series is any indication of Marathon nights to come, it's worth the 3-Series Pass offered by EST. It's a piquant potpourri that'll keep everyone satisfied and, rare these days, wowed.