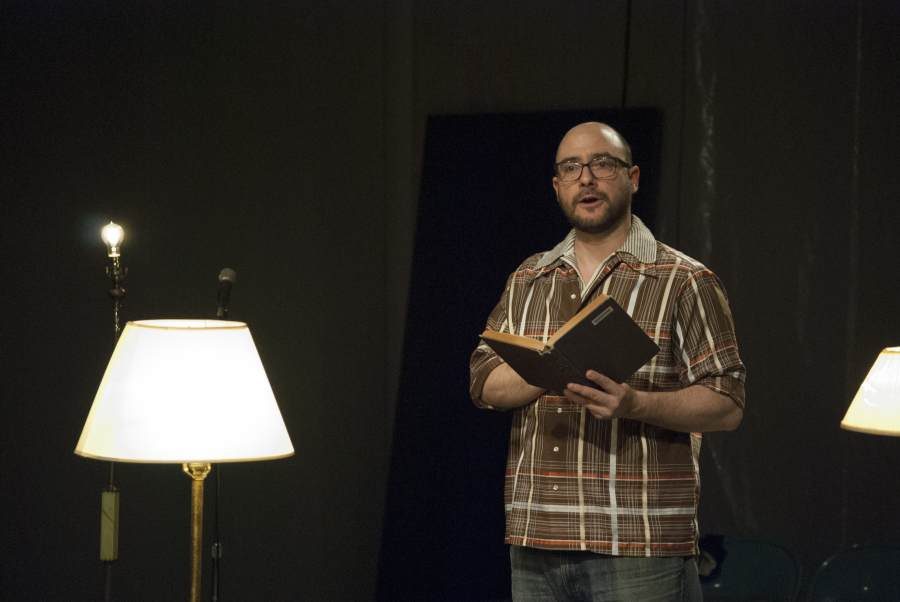

Roberto Bolaño’s Distant Star takes place in the aftermath of the Chilean coup that saw Augusto Pinochet oust and murder President Salvador Allende, in order to impose a reign of terror that would alter the political landscape in Latin America for generations to come. In his meditative novel, Bolaño asks if it was possible to create art in this environment of fear, paranoia and deceit. Now Brooklyn based theatre company Caborca, led by artistic director Javier Antonio González, have turned the novel into a play which couldn’t have arrived at a more needed time. I attended a rehearsal of the play and discussed the themes in the work with González and producing director David Skeist who also gives life to the narrator.

Distant Star is such a maze of a book to try to put onstage, how did you find the way to turn it into a play?

Javier Antonio González: I love that you said it’s a maze, because the play tries to be a labyrinth. I kept thinking about tunnels, opening doors and not knowing what you’ll run into. It’s a bit of a collage, it brings together skywriting with dialogue, a manifesto in the middle of it, a declaration of someone’s work. We wove it using a lot of text from the book.

I’ve never read Bolaño in English, what translation did you use to write the play?

Javier Antonio González: Chris Andrews and Natasha Wimmer, heroes of mine, have translated most of the works into English. I read the book in English first and then in Spanish, the adaptation owes a lot to Chris’ work.

Did English bring any new elements to the work that weren’t there in Spanish?

Javier Antonio González: English is more straightforward, after so many years there are little sections that I go back to and wonder where I got them from. But then I go to the book and they make sense, they’re there. Chris Andrews is Australian so the translation has many British elements.

David Skeist: We were calling apartments “flats” which was weird.

David, can you talk about your character?

David Skeist: I play the narrator.

Arturo?

Javier Antonio González: We never know his name, but in the script we called him Arturo.

David Skeist: I also play another character, the whole cast plays multiple roles.

What’s it like to play a nameless character? The narrator in the book is such a cipher.

David Skeist: He’s purely subjective, you get no objective information about him. Having read a fair amount of Bolaño his narrators are so fascinating, they’re not impartial, you question them. I think the way all his narrators process information and question themselves, so much is revealed of who they are based on how they think. So playing the character it’s all there in his perspectives, how he reinvents himself and his unreliability, which is what I found intrinsically relatable.

He’s kinda creepy.

David Skeist: Yeah, he’s charming and creepy. It’s so interesting you say that about the narrator, because the duality of the narrator and Carlos is so fascinating.

There’s a lot made about names in the book and duality. It made me think of things like Pixar’s Up or something like Bergman’s Persona. Did you need external references in which other artists played with that duality?

Javier Antonio Gonzalez: I didn’t need them, I just gravitate towards them, like Laura Dern in Inland Empire, she plays three different characters and they’re all the same person. In a way there’s something very universal and simple about this, because they’re stories of people facing who they are. Bergman comes into mind as well, so does Lynch, doppelganger stories too.

David Skeist: I think as human beings we’re defined as much by what we are as what we’re in opposition to. We create ourselves in some ways in opposition to our parents, inconformity to society around us. The road not taken is always so present.

The narrator is also a bit of an asshole, in the book he’s always trashing other people’s work. But there’s also an element of envy, of knowing other people are trying things he’s not doing. The book takes place during Pinochet’s regime of horror in Chile, and it’s no coincidence that the play is coming out as America deals with its own fascist. What’s it like to do this play today?

Javier Antonio González: The book as a major classic, even before this reality, shook us. It took hold of us. Of course it feels more urgent now, I don’t know how else to explain how present and urgent it is.

David Skeist: We’ve been developing this project for over 10 years. Our first meeting with Abrons which we’d scheduled weeks in advance happened the day after the election. There was a kind of dark magic to that, nobody knew what the hell to say and there we were to talk about a project about fascism. Suddenly there was something to say, there was a voice for us to filter our anxiety, sadness and rage. Things that have only continued to escalate. Bolaño’s work isn’t didactic, he ties and unties knots of ideology and fascism, aggression, artistic aspirations. Art, like any kind of weapon, you use how to use against fascism or for it. How we wield this weapon is something we’ve been considering and asking since we started work on this.

Javier Antonio González: By now our actors are also closer to the age of the narrator rather than the poets. The play for us has been a laboratory for us to develop this conscience.

David Skeist: We started this at the tailend of the Bush administration, we were first discovering Bolaño, Naomi Klein and other writers who dealt with US intervention. We worked on the project through the Obama administration and while things changed, a lot remained the same. The feeling of being an American had changed, but now as we do the project in this time it’s been a rollercoaster of a journey as we’re back to asking questions of ideology and fascism. We’re linking ideas in the book to this new political reality which seemed inconceivable in the previous administration.

Has the current political situation led you to wonder why artists keep creating art when the world is in such turmoil?

Javier Antonio González: I believe in the archival nature of the thing we’re making. I love politics but I’m also about art for art’s sake. Our play is an expression of what we feel, this work by its very existence is already in a way radical because it exists. I think that’s why we’re so fascinated by figures like Leni Riefenstahl, who made art which is art regardless of her ideology. She was a genius who pushed several languages,she created form. But how do we reconcile that with her ideology? It’s so complex. But then we think of someone like Roman Polanski, we judge art based on political ideology but what about personal life? I try to think less about those, but it’s also what obsesses us. Should they be allowed to be this way?

I often tell people if we knew about the personal lives of people whose art is hanging in museums, someone would suggest we go close down the Louvre.

David Skeist: We listen to musical composers who are known rapists!

Javier Antonio González: How do we separate the art from the personal narrative?

David Skeist: One of the most painfully complicated questions Distant Star asks is how we separate personal lives from art, but also how do we unpack our own accountability. I may choose to watch a film or play by someone who did appalling things, I can and will choose to do that, but I can’t wash my hands clean of the choice to do that. The narrator in the book is wrestling with the existence of Carlos Wieder, but what tortures him most is his own obsession, his own aesthetic inaction in the face of the shock that changed his generation.

Bolaño is such a part of your work that you named your company after a fictitious magazine from one of his works. If you could create your own Caborca magazine what would you put in it?

David Skeist: We’ve thought about it, we’ve talked about it. About creating a magazine with our community.

Javier Antonio González: We have a lot of writers in our company so we’d include short plays, something by a Puerto Rican poet, some political essays. I’d think of the Puerto Rico and New York audiences, which doesn’t necessarily mean the New Yorican audiences. I’d probably do an issue of just poetry and one of fiction.

David Skeist: We’ve come to exist at a bit of a nexus, theatre and film companies and collectives that all exist independently outside of the system, and we are the same artists, performers, writers and directors. We all work with each other and for me one of the dreams in having something like a magazine would be to have an artifact to document what were, what are this kind of slightly amorphous, but centered collection of writers, thinkers and dreamers existing outside of the system. What were they thinking about, what was their perspective during this time?

Distant Star is now running. For more information click here.