Two-handers surrounding taboo, cultural and generational crossed-lines and a bit of frothy spectacle and are on order for the last installment of Ensemble Studio Theatre's Marathon of One-Act Plays. Now boasting a special Drama Desk for supporting new work, the festival is a fitting affirmation of EST's commitment, even if Series C is a bit of mixed nuts.

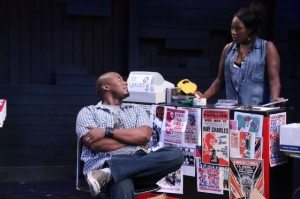

The night kicks off with Angela Hanks' Devil Music. JJ (whose embarrassing full name is the source of much of the playlet's ammunition) and Geraldine are closing shop on their record store for good. As they box up inventory, the longtime friends and erstwhile lovers unbox a lot of unresolved feelings for each other, the fate of the store and the nature of love. Morgan Gould's snappy direction and solid performances by Daniel Morgan Shelley and Crystal Lucas-Perry (who shines in a great, if unearned monologue) hold the piece together. But like JJ's 500 order of Tony! Toni! Toné! singles, the same beats are played too much with too little variety for the play to rise above the same tired tonic.

Daniel Reitz's Good Afternoon fares better with some very tricky material. A new neighbor and a registered sex offender (announcing his status per court order) is not the stuff of typical meet cutes, yet somehow, without endorsement or outright judgment of the flawed leads, it manages to flow into something -- I shudder to say it -- 'sweet.' At least, as sweet as two damaged people feeding their ids can be. Haskell King as the taciturn offender, Glen, and Kersti Bryan as Lorrie, the one-time precocious seducer of an older man, are electric together and well-realized on their own, and Jules Ochea directs with just the right touch of reality, pathos and comedy.

A sweet father-daughter piece leads us into intermission and washes the stage with a flood of stars as the players bob by on a boat. The Science of Stars and Fathers and Daughters by Darcy Fowler sees Tom and Madelyn row through the years in a Memorial Day Weekend tradition -- one senses he gets her on weekends and he's split with her mother from the jump. The constellations above are the one constant as Emma Galvin's Madelyn shifts from mimicking her father, to parroting Audrey Hepburn's Holly Golightly, to growing apart from Dad and their ritual as she matures. Galvin's transformations are something to behold and Michael Cullen anchors the play. I wondered, though, if the piece, which makes use of blackout transitions, might not feel more fluid without them. If the convention feels creaky, director (and EST literary manager) Linsay Firman's staging imbues the piece with the feel of something classic. Fitting, as the play circles back to the stars whose light, Madelyn says, echoing her father once more, "was created many, many years before us."

The most effective play follows intermission. The Talk by France-Luce Benson, directed by Elizabeth Van Dyke, answers Fowler's offering of father-daughter with mother-daughter, with hilarious and heartfelt results. Sleeping in her childhood bed, Claire is awoken at three in the morning by her mother who comes bearing a package no child wants to see on their parent's person -- I'll leave it at that. The crackling, well-drawn script unfolds in real time as Manu (the remarkable Lizan Mitchel with a wonderful Haitian accent) runs the litany of things Sharina Martin's Claire (just as marvelous) doesn't want to hear -- she's not just a yoga teacher, she has a Masters in Eastern Philosophy! The ways these women admire, resent, and ultimately fail to understand before understanding each other is very specific and somehow universal. I'm sure many in the audience had flashbacks to the same kinds of circular arguments with their parentals when they strayed a bit from their approved path. The hardly alluded to reason for Claire's stay at home after a life of travel gives the scene depth rarely touched on so completely in so short a work. And it's really funny, too.

Also bringing the yucks is the wonderfully, violently, crudely and delightfully subversive Double Suicide At Ueno Park by Leah Nanako Winkler. Starring three anthropomorphic cherry trees (a Greek trio of sorts played loftily -- you'll see -- by Yurika Ohno, Kana Hatakeyama and Shiro Ichikawa) and a couple of teenage courtesans, the play snipes at old, but abiding notions of femininity, the fetishization of geishas, ritual suicide and other destructive tropes that linger around the Western (though not exclusively) idea of Japan, with deadly precision. The angle of attack in Winkler's script and John Giampietro and Assistant Director Mikhaela Mahoney's elaborate blossom-blown staging, is anything but subtle. Akemi (a bubbly, brilliant Sasha Diamond) and Onoe (Jo Mei, terrific) speak to the beauty of impermanence ("Our purpose is similar to that of the cherry blossoms...to benefit visitors with our spirit...until we die beautifully"), but also offer earnest, chipper and beyond-all-subtext musings like: 'Do you think that the female sex are creatures of deep sin, destined in death to be thrown into the pond of our own menstrual blood in hell?" The effect is stilted by design, letting florid, lurid language free from subjects that are typically presented as discreet or mum. It's the perfect idiom for the themes explored here. Something has been lost in translation; Winkler's telling us we're missing something big. But when the girls encounter a virile, but mumbling Samurai (Don Castro) they leverage their "womanly frailty" to end things on their own terms. I think EST may well be doing the same with its curation in choosing to cap the Marathon with this play. It's exactly the kind of work they're getting recognized for.