It seems that the older we get, the less we understand our parents, even if aging would suggest that adulthood would in fact connect us more to them. In Richard Greenberg’s Our Mother's Brief Affair siblings Abby (Kate Arrington) and Seth (Greg Keller) must come to terms with their dying mother Anna’s (Linda Lavin) revelation that she had a very meaningful affair when they were teenagers. An exercise in how memory affects storytelling, the play allows all of its characters at one point or another to become narrators, the problem is, none of them are very reliable, so who we believe is strictly up to us.

We learn from her children that Anna announced her imminent death on more than one occasion, to the point where she became a little like the infamous boy who cried wolf. She was also an embellisher of truths and glamorous beyond what her Long Island upbringing should have allowed, and wore a Burberry trenchcoat and a silk scarf on the rare occasion when she had errands to run in the city. We learn from Anna, that her sophistication came not without its amount of self awareness, as she was desperate to prove to the world she was much more than they expected, and we learn that the act of dressing up and running errands was an escape from the inner hell she’d created for herself.

By no means is this a story of a desperate housewife looking for excitement, instead it’s a warm, intellectually complex essay about the difficulty of forgiving ourselves for our sins. As we learn about the affair of the title we come to terms with how it’s perceived by members of different generations, Anna’s adult children squirm at the idea of their mother having intercourse with someone who wasn’t their father (not that intercourse with their father would have made them squirm any less), while Anna looks at it as a touching chapter that served a purpose and then was over.

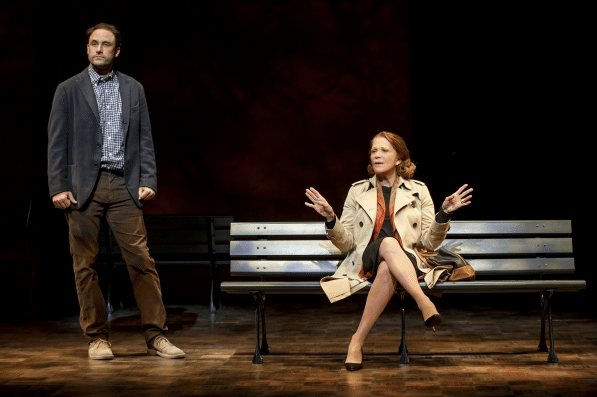

Sensibly directed by Lynne Meadow, the play can be enjoyed as a light comedy with charming performances from its ensemble, Lavin gives a sizzling, beautiful performance allowing herself to be sensual, sometimes bitter, and in a miraculous feat of transformation aging decades with the mere shift of her posture. Her Anna is the mother of our friends we secretly wished would adopt us, and overall a woman you want to engage in conversation with. Keller is fittingly anxious, like a Woody Allen character whose Xanax is about to wear off, and Arrington’s aggressive nonchalant-ness is the epitome of effortless charm.

But if one allows oneself to look beyond its stylish surface, there is a richly layered account of how we live according to the truths we tell ourselves, some of which never become facts to others. This duality is best perceived by how the character of the lover is played by the same actor who plays Anna’s husband (John Proccacino), perhaps a symbol of how she was unfaithful of body, but never of heart, or instead a melancholy look at how she chose to remember her husband with the image of the last man who thrilled and understood her.