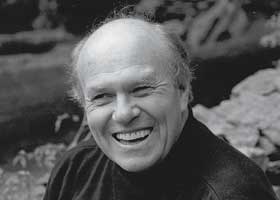

It’s no small thing for Tom Dulack to claim that putting on The Road to Damascus at 59E59 has been “the best theater experience of [his] entire life.” A professor of English Literature at University of Connecticut and a novelist to boot, Dulack has been writing plays for decades, gathering numerous awards along the way. Though Road to Damascus, a riveting, controversial political drama, is not his first hot button play, it shows him at a pinnacle of fearless, boundary pressing experimentation. It is the kind of incendiary material that makes going to the theater such an exciting and rewarding experience.

It’s no small thing for Tom Dulack to claim that putting on The Road to Damascus at 59E59 has been “the best theater experience of [his] entire life.” A professor of English Literature at University of Connecticut and a novelist to boot, Dulack has been writing plays for decades, gathering numerous awards along the way. Though Road to Damascus, a riveting, controversial political drama, is not his first hot button play, it shows him at a pinnacle of fearless, boundary pressing experimentation. It is the kind of incendiary material that makes going to the theater such an exciting and rewarding experience.

Dulack spoke with me about being a lapsed-Catholic, writing about real life events, and trying to take a stand in a political climate driven so often by terror and greed.

Can you talk a little bit about the process of writing/revising the play? You seem so knowledgeable about the topics you discuss -- the politics -- how did your play change and adapt over the years?

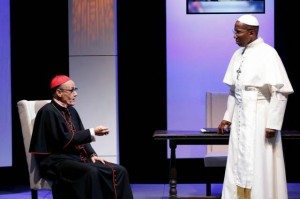

What happened was in 2007, I was still very angry about the Iraq War, and the invasion, and the Bush/Cheney axis and so forth, and I wrote the play as a kind of a critique of the Bush administration and foreign policy, and the novelty of the first black Pope. I mean, I had the idea of what would happen if somebody actually exerted some moral authority in this quagmire and said no. Because I’m an ex-Roman Catholic or a lapsed Roman Catholic or whatever you want to call it, whatever we are, I’ve always stayed current with what’s going on and I’ve always been fascinated by the Vatican and Vatican politics and stuff. Through my marriage, we’re remotely connected to some high Catholics in Italy, and it’s always been a kind of ongoing thing with me. And then I thought about the first black pope… people got very excited about that at the time. We did a reading again at Sardi’s… the first reading of the play way back when. And people got excited. A guy in Brussels commissioned a French translation for the National Theater there, we had interest coming out of London, so forth and so on.

And then, Obama got elected, and it was an odd thing, because it seemed like it took the wind out of his sails… the first black Pope, which was a fiction, was replaced by the first black President, which was a reality, and so the translation in French kind of died and everything kind of died, which is fine, it just happened. We continued to try to get the play produced, and nobody was biting, so it just went into the drawer. And then as things began to evolve under the Obama administration, suddenly it was current again. And people asked, “you were so prescient, how did you know about Syria?” And I said, well, I didn’t know about Syria. I just sat and looked around and thought, if we continue in the way we’re going, what’s going to be down the road? At that point, Syria was quiet and so I said “Syria, Damascus.” And I loved the idea of The Road to Damascus as the title, and so it had to be Syria as opposed to Jordan or Yemen or some place else.

You mention Bush and Cheney, Hillary Clinton, Benghazi... Where was that line for you between mining from real life events and finding the fantasy element?

I think the line was, once I set the play in the “not too distant future,” that allowed me to make those kind of references. Real references. Because then it was an imagined past. And every production, when [the character] Bowles mentions that “Hillary brought her in to clean up the immigration mess,” there’s always a laugh, because the audience recognizes that I’m referring to Hillary as the President, and she served her two terms, and then somebody else came in. So that was a big thing to free me up, and then I could make exact parallels, because we were in the future, and the parallels are almost one to one. I mean the invasion that I write about in this play is pretty much exactly the Iraq invasion of 2003.

The idea of a political thriller is kind of a novel concept to me for the theater. Audiences certainly have a preconceived set of notions about what that looks like on film - explosions, action sequences, quick cuts and dramatic music. What made you decide that this genre was doable on stage, and do you think it adapts well to the theater?

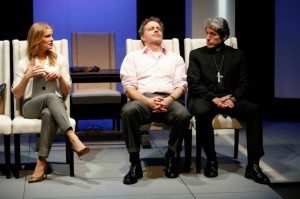

Well, I never intended it to be a political thriller. That sobriquet has been applied by other people to it. I never thought of it as a political thriller, I thought of it as a drama with a ticking clock, you know? That was built into it. And I arbitrarily set six days on it to increase the tension of the play in the sense of a ticking clock. A woman yesterday afternoon at the show… it was the first time I heard the phrase in fact. She said, “this is the best thriller I’ve ever seen.” And I kind of jumped, because I wasn’t seeing it in terms of a thriller. And otherwise, I’d never thought of it as a different kind of genre. The staging of the play as it stands is exactly as I wrote. And I wrote it that way because of all the economic realities of the theater today. I was envisioning a way to do this play without a set, where the characters would just come on and off, and originally there were no projections or anything, so whenever [the character] Nadia was giving a news broadcast she would just walk on and give the broadcast and walk off. At one point I said to Michael [Parva, director], “how are you planning to stage this?” And he said, “well, just the way you’ve written it.” So you know, it’s gussied up a little bit, and it looks very well because the costumes are so great and everything, but then the projections and the videos and stuff, that was all added once we were underway, once we got into production. Then we discussed it, you know, how do we do this, how do we do that? They said, “we could use video, we could use television, do you want to do that?” And I thought, let’s try it and see. Over the years, I’ve always been against this kind of thing in theater. I’ve never liked mixed media, like music. I’ve never even liked music.

You wanted it to be minimal, stripped down?

Yeah, this is minimal, but I didn’t even like minimal. Until I ran into this production team, and I have to tell you, they are the best bunch of smart, young people I have ever encountered. I mean they’re phenomenal, all of them. The sound design, the lighting, the costumes, the set. I think the set is marvelous. They’re just terrific. And they came up with all of this stuff. Each time I would see it I was just thrilled by it. Then Michael blended it all so well. Cutting into her news broadcasts with her overlapping in reality against the video. At the very end, well I don’t want to talk about the end… (laughs)

I wasn’t planning, I wasn’t doing any genre busting. I think of it as it Shakespearean staging. Originally I didn’t have any division between the scenes - one scene flowed into another. So these scene breaks with musical interludes became somehow necessary because of costuming and so forth and so on. But this play could be done on a bare stage without any of that. I mean obviously it wouldn’t have the same impact, but the story would be told and I think it would be clear.

Back to something you mentioned earlier, I wonder if you could talk a bit about the religious implications of the play. The Pope is acting like a head of state, and for a "political" play, religion is potentially the central conflict. What made you decide to have religion play such a heavy role?

I pay a lot of attention, as I said, to what’s going on in Rome over the years. I just do. And I’ve written about religious subjects really quite a lot. I mean my best novel is something called The Stigmata of Dr. Constantine, in which a bishop is the second lead character in the book. I wrote a play about Saint Francis, which is just a terrific play, and I can’t get anybody to do it, because it’s about a Saint, you know? But as things have been going on, and as I’ve thought the Vatican moral posture was getting more and more degraded by this whole gang running things there, and the scandals and the sex, and the passing the buck. And then the complete moral surrender on the part of all the religious leaders in the world.

So all these things happened. And I was very sensitive to that when I was a kid, believe it or not. I latched on very early to what Pope Pius XII was doing. I was just a kid in school, and we had this big picture of Pope Pius at the front of the classroom, and I hated him, I hated the picture. And once I got a little bit older, and found out a little bit about what happened in Rome during the war, during the Holocaust and stuff, and what I have taken ever since as the frank anti-Semitism of the Church, I’ve paid a lot of attention to this, and to the idea of what if a Pope were finally elected… the notion of a great pope, and the logical coming out of Africa, who really would do something, who would do what religious leaders are supposed to do and never do.

And this became an irresistible idea to me, and the Papacy when Bush came in to invade Iraq, the Pope made a protest, and there was a delegation that came in, and Bush listened, and then it went away. But what if somebody really drew a line and said no? This is it. No more. We’re not going to do this. So I develop in the play where finally the four of them are meeting in Damascus, and what if, what would happen? And what would the American government or any government do in the face of some kind of united thing where Islam and Catholicism and everybody else said that’s it. None of us are in favor of killing anybody, we won’t tolerate it, this is not religion. None of this represents us. And we won’t have you invading us and pretending it’s on any other grounds than what it is. What would be the impact? What would be the impact of that? And it seemed to me to be an irresistible combination, and I wanted to explore it.

I don't want to spoil the ending for our readers obviously, but let's just say you think it's going to go one way and then things take a dramatic turn. Speaking about all that you just said, considering the passion behind your project, do you think your play is ultimately optimistic or pessimistic?

We talked a lot about this in rehearsal. And Michael was passionate about it, and I absolutely agreed with him, and we did everything possible to produce this, is that we didn’t want a downer, we didn’t want a pessimistic play. We didn’t want the audience to come out feeling down. And you know, I’ve seen five shows this week, and I haven’t heard people being down at the end of it… what we were trying to do and at every opportunity what I was doing, was supporting the notion that this play is about what can happen when one man takes a stand, takes a moral stand. That it’s possible for people to stand up and make a difference. And that’s the ultimate message of the play, and the people in the play, you know, Hobhouse and Nadia and the Pope, they’re transformative characters, and at the end of the play without giving anything away, you know, we have a vision. And you can call it a fantasy, and maybe it is a fantasy, but there is a vision at the end of the play, and I think it’s very clear how wonderful things could be, and how actually attainable they are. This could happen if enough of the right people got together and said “ok, we’re gonna do this.”

I don't mean to sound hyperbolic, but were you ever scared when you were writing this play about how bold and potentially controversial it is? Or did that just fuel your fire and make you want to push forward even more?

I don't mean to sound hyperbolic, but were you ever scared when you were writing this play about how bold and potentially controversial it is? Or did that just fuel your fire and make you want to push forward even more?

You know, when I was first writing it, of course, we had terror in the world, but it was nothing like what we have now. So that wasn’t really an issue, and I’ve always kind of pushed the envelope, I’m just the kind of person who does push the envelope. So nothing I’ve written is not, in a sense, controversial. I write about high emotional things with high emotional content. And that’s race and religion and sex and politics. These are the red button issues for me that immediately get a lot of emotion going in the audience before they come in. So all my work has been in one way or another controversial. If my play isn’t going to be out on the cutting edge somewhere then I can’t write it, it doesn’t interest me. You know, I don’t need to write about how people are unhappy because their parents were mean to them when they were children.

But having said all of that, some other interviewer asked me, the first question he asked me, was “aren’t you scared a little bit?” And I have to say I am a little bit. Because in this climate, you know, with bombs going off and with crazy people out there… it gives me pause, it really does give me pause. After 9/11, this group came to BAM, just a couple weeks after 9/11, a dance company. And the whole idea was, we have to make a statement. We have to show the terrorists who did this that they’re not gonna change our lives by this. We’ve got to go to the theater. They were putting the American flag up at the end of the play, singing the national anthem. And we went, and the fires were still burning, and we went to BAM, and somebody made a speech -- it was the first performance at BAM after 9/11. And we were scared, you know? We didn’t know what was going to happen. But we were also making a statement. And this is life now. This is life in America now. And what do we do? We cower, or we go out and take a stand. It’s a dangerous world we’re living in. That’s how I feel going to New York and working on this play. It’s scary. But you have to do it.

The Road to Damascus plays through March 1 at 59E59