The notion of dramatizing the story of a white kid from the suburbs turned failed NYU film student, living in a huge Manhattan apartment on his father's dime hits me at gut level as the kind of eye rolling, self-aggrandizing "hipster" punchline that I go out of my way to avoid. Yet what Jesse Eisenberg has crafted with this plot in the New Group's presentation of The Spoils, the play he wrote and is currently starring in at the Pershing Square Signature Center, manages to be at once painstakingly sincere, brutally honest, and anything but obvious.

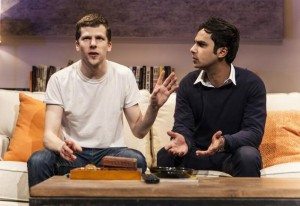

The two act story takes place in the living area and offset kitchen of a modern but fairly generic, bought-the-furnished-model type of apartment, with a balcony and killer skyline view. Eisenberg plays Ben, an NYU film school dropout who spends his days smoking pot, drinking, and failing to realize his film -- ahem -- "compelling collage of life" that will cement his genius and catapult him to smug success. His roommate, whom he credits himself for "discovering," and arbitrarily either demands or refuses to accept rent from, is Kalyan, a highly intelligent, optimistic Nepalese immigrant, studying for an MBA at NYU and working towards a career on Wall Street. Played by Kunal Nayyar of The Big Bang Theory, Kalyan cares for Ben despite his nastiness, and together the two of them make a charismatic and dynamic odd couple, capable of evoking huge laughs with their quick and often endearing repartee, making it all the more painful to watch as Ben pushes the good hearted and hard working Kalyan away with his acerbic bile and pathological self-loathing.

Annapurna Sriram, Michael Zegen, and Erin Darke round out the cast as Reshma, Kalyan's type-A med student girlfriend who isn't afraid to call Ben on his nonsense, and Ted and Sarah, a recently engaged couple with whom Ben went to elementary school and has suddenly taken a special interest in based on an obsessive belief that Sarah may be the love of his life.

Though recognizable celebrity can serve to distract in an intimate setting, Eisenberg brilliantly mines the celebrity cache he's working with, most notably his. The preconceived notions I had about the "poor little rich boy" trope, or the awkward anti-hero who scores the bombshell with his big mouth, characters for which Eisenberg is known in his cinematic career, made it all the more satisfying to see them dispelled one by one in an almost flagellatory sense of self-awareness. The Spoils is ambitious in its masochistic scope, and the theme of not merely arrested, but tormentedly stunted development bleeds through at the core. In one terrific scene, the two couples, Kalyan and Reshma, Ted and Sarah, sit around the dinner table -- Ben's table, ostensibly -- in fancy clothes and congratulate each other about being in grownup relationships and having grownup jobs, all while white T-shirt and jeans clad Ben sits a full head below, sunken in the easy chair he's pulled to the table, diving headfirst into every substance he can find in an effort to dampen the evening.

Throughout the play, Eisenberg is razor sharp in his meta-dialogue about a certain sect of privileged millennial society, pressing upon the problematic duality of a generation who has, on one hand, grown up aware of their own privilege and is politically "enlightened." Upon a suggestion to "get drinks," Ben scoffs, "what kind of bourgeois bullshit is that? You never hear someone in Democratic Republic of the fucking Congo ask to 'get together for drinks.'" Yet by endlessly spouting cultural stereotypes and generic, offensive platitudes about his roommate, his roommate's Indian girlfriend, filmmakers, filmgoers, bankers, he proves himself ultimately unable to find the limits of his arrogance, and crushes race, culture, gender and beyond in his gristmill of anger, casting about as a bitter and confused pariah in a self-imposed exile.

The play's first act has a low key, hangout vibe, as the group drinks, smokes, and chats. But Eisenberg wants to create drama with a capital D, and the capable actors have no trouble keeping up when he does so in the second act and Ben drags his world down into chaos. While the second act is compelling and disturbing, the play addresses so openly the demons of a certain "millennial" sect -- one to which I belong and to which this play seems to speak, even through nods to Harry Potter and the muted airs of "Waterfalls" by TLC -- I think I would have been just as content to see more of Act One, more of, to paraphrase another famous New Yorker, "a show about nothing," seemingly vacuous in its content and yet deeply revelatory about a generation that just can't seem to get their act together.