There is usually a moment in all of Anna Ziegler’s plays where you, as an audience member, get the sense that the feelings onstage (or on the page if you’re reading them) had never been felt before. Whether it’s the teenagers in Life Science coming to terms with the notion of life existing beyond the confines of their high school, to the title friends of BFF, realizing that no love will truly compare to that of a close friend, or the characters in A Delicate Ship understanding that they might have already loved and lost, Ms. Ziegler’s works all are united by the thread of discovery, both of the self and the other.

Perhaps this is most effectively encompassed in the scene in Photograph 51, where scientist Rosalind Franklin first sees the double helix structure of DNA in a seemingly simple X-ray diffraction. It’s true at that moment that no other human being before her, had seen what can be defined as the composition of life itself, but through Ms. Ziegler’s observations the moment becomes as important as any of the emotional discoveries her other characters have made. In her deeply humanistic plays, we’re all the same, regardless of our upbringing, age or gender.

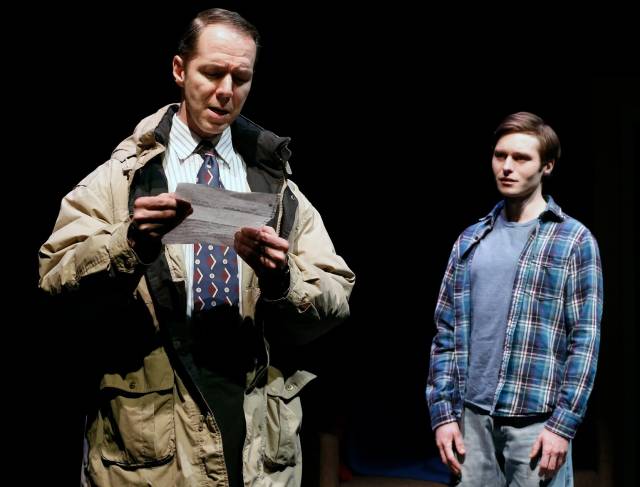

In Boy for instance (reviewed here) she focuses her attention on Samantha, an inquisitive little girl who has no idea she was actually born male; thanks to an effective dramatic device we realize she eventually found out and chose to live as a man named Adam. That both the girl and the man are played by one actor, aren’t only a stroke of aesthetic brilliance and a noble artistic statement, they are reminders of universality, that go beyond the scientific or the spiritual.

Other recurring themes in Ms. Ziegler’s work include the effects of memory, our roles in creation (artistic and personal), and thanks to her ease in writing simple, but unforgettable prose, her works are preserved in your mind long after you’ve experienced them. With the intention of finding out more about the connections between her works, as well as her writing techniques, I seeked to know Ms. Ziegler’s thoughts on a few questions, which she was kind enough to respond with the grace and insight of her marvelous oeuvre.

A Delicate Ship was as obsessed with memory as Photograph 51 is fascinated with legacy. Do you feel that the disconnect between how we remember, and how history records events is something that should be more discussed in art?

I think I am less interested in personal memory vs. historical memory than I am in the fallibility of memory in general – how our memories and those of others experiencing the same event can differ significantly, and how even within ourselves there is no neat or consistent narrative of the story of our lives. To me those discrepancies make for fascinating, theatrical material.

In A Delicate Ship we do a flash forward when we encounter Sarah and Sam years in the future, as they are coming to terms with events set in the “present”. Do you ever take on writing as a method to help you understand events of your own life? Is writing therapeutic in a sense?

In A Delicate Ship we do a flash forward when we encounter Sarah and Sam years in the future, as they are coming to terms with events set in the “present”. Do you ever take on writing as a method to help you understand events of your own life? Is writing therapeutic in a sense?

I suppose I probably do to a certain extent. I think it’s hard to write well about things that don’t feel at least somewhat personal, even when not at all autobiographical. A recent example is my play The Last Match, which, on the surface, is about a pro tennis player on the verge of retirement coming to terms with his identity shifting but which I wrote shortly after having a baby, when my identity was shifting too. I think when one is really writing for oneself, and has managed to shut off the negative voices usually scrolling through one’s head (“this is such a bad idea;” “no one would ever want to do this play”), then the act of writing can be powerfully therapeutic. But that’s quite rare, at least for me.

The way you deal with time in A Delicate Ship feels like it required mathematical equations. Would you say your work in any way is trying to close the alleged gap between art and science?

This question strikes me as very funny, since, for most of my life, I was deathly afraid of math and science. Right now, for some reason, I am drawn to stories that weave those worlds together—maybe a result of being scared for so long and then seeing science wasn’t actually so scary. But I don’t think math or science come into play in A Delicate Ship —there were no complicated algorithms at work, just the weirdness of my own mind and the way I see the world.

We could say that Photograph 51 is very similar to Novel in how they’re about people consciously “writing their history” as they live. Sitting down to write these two plays, how were you able to make them feel contained but also filled with possibility, like they could go anywhere?

I’m not sure how to answer that except to say that one thing I find both immensely satisfying and deeply frustrating about writing (and life) is that stories never seem to end. One person’s story dovetails into another’s; nothing stands on its own without affecting the people and things around it. I don’t think we can escape that.

Life Science and A Delicate Ship both have extremely existential love triangles, in which people who think of themselves as being in love, are never sure about the truth of their feelings. Do you find that the idea of romance that has been created by fiction has set up impossible standards to fulfill in real life love?

Or maybe it’s less that fictional romance sets impossible standards than that it doesn’t tend to reflect my experience or the experience of my friends, which usually seems thornier and more complex—and more changeable. People’s feelings shift all the time in a way that I don’t think movie romance, for instance, tends to capture.

As a playwright do you discover new things about your work when you see it performed by different actors? Was Photograph 51 with Nicole Kidman a completely different experience for you than the New York production for example?

It was different on so many levels. And that had as much to do with it being performed in England as it did with there being a movie star involved and the attention that went along with that. The British audience took very different things from the script, laughed at different things, took umbrage at different things, and that taught me a lot. Everything is so fluid, and a reflection as much of the audience as of what’s on stage.

You’ve adapted Photograph 51 into a screenplay. Are you compelled to adapt the works of other writers into different mediums? Do you have reservations about other writers adapting your works?

I do have a yen to try my hand at adapting other writers’ works right now. I like the idea of the story being set already and then getting to play with structure and form. And I would love for other writers to adapt my work. Maybe they could solve things I couldn’t solve myself. Good luck to them.

Do you create entire lives for the characters in your plays? I’m mostly curious about the kids in Life Science, who have the world ahead of them when we leave them.

Yes and no. Entire lives? I have a sense, with most of my characters, of what their lives are like, but I haven’t necessarily created details and backstory that don’t appear in the play itself. It’s a useful exercise when you’re feeling stuck about a character but I don’t find every character needs that kind of dissection. Usually, as the writer you just feel you know these people already; they’ve emerged fully formed in some sense.

Photograph 51 and Boy both deal with the concept of gender in ways that surprisingly make them ideal companion pieces, because they make the audience ponder the different paths their lives would take if they identified as a different gender. Are you often surprised about the ways in which your plays link with each other?

That’s a very interesting connection to make! I hadn’t considered that link. But I think in most cases in my work the similarities in theme and form are glaring. I tend to go back to the same territory, usually without quite meaning to. There must be certain things we are always trying to work out, and so we return to them in different guises.

There are several instances in your works in which characters address the audience, becoming mirrors of people sitting in the dark. Do you find that the confrontational nature of this device might be too scary for some? Are you interested in provoking reactions even if they can be deemed as negative, or stressful at times?

No, not really. I think I go back again and again to direct address because it feels so uniquely theatrical, and because it adds this whole other texture to the play. I love going in and out of it in a way that, I hope, keeps the audience on its toes, and listening.

Did your discovery of Rosalind Franklin lead you to explore the lives of other female scientists with lives that need to be told onstage? A play about Hedy Lamarr would be something I’d love to see for instance.

People (mostly scientists) have, at this point, sent me numerous unsolicited (but welcome) suggestions of other scientists –male and female—about whom I should write. There are so many great stories out there. Hedy Lamarr is a terrific and sad one. I’m not sure I’m going to tackle other female scientists – at least not for the time being – but I encourage other playwrights to look for those stories. They’re a gold mine.

Do you have a secret tip you'd like to share with budding playwrights? Any rituals/tricks that help you write?

If anything, my tip is not to worry about other people’s rituals. I’ve found that I can’t really control when I feel inspired and want to write and that forcing it is never very fruitful. I’m a pretty erratic writer; I don’t have a routine. I used to feel bad about that, but I’ve come to accept it now. We all have different rhythms, after all, and I think it’s probably wise to heed them.

For more on Ms. Ziegler visit her official website. For tickets and more information to Boy click here.