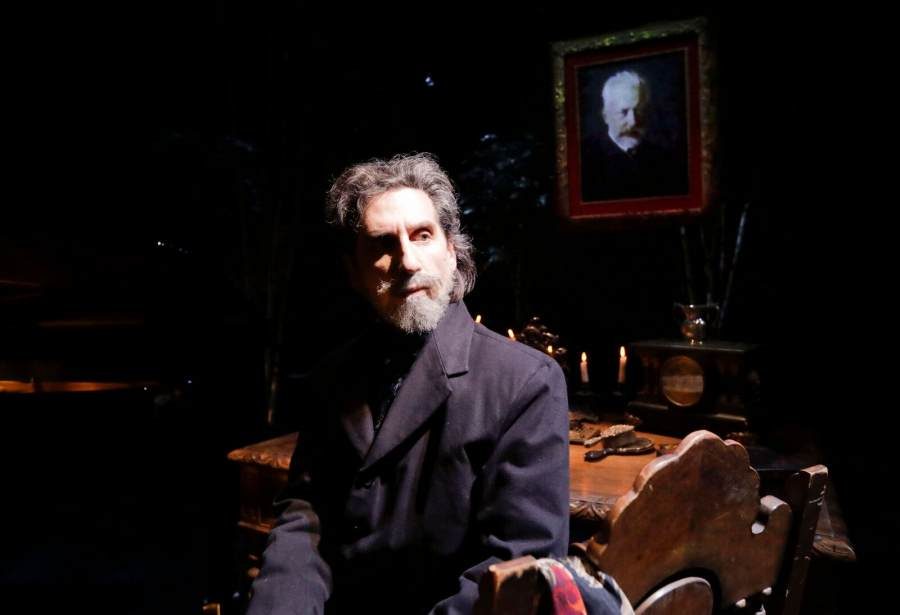

Throughout the adult life of the great Russian composer Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky, he fixated on one idea: his homosexuality, how to closet it and how to compensate for it. Hershey Felder’s one-man show Our Great Tchaikovsky, currently showing at the Mountain View Center for the Performing Arts under the aegis of TheatreWorks Silicon Valley, tackles this central idea in bringing the classical composer to life, commenting on attitudes towards homosexuality under Tsarist rule and today. The title of the show highlights how the Soviets and Russians idolized the composer while expunging references to his sexuality.

Felder melds virtuosic piano playing with a docudrama approach to character and narrative. An artist who has made a career creating shows about composers and pianists—Lizst, Chopin, Beethoven and Gershwin, among others—he takes a somewhat predictable chronological approach to the artist’s career, using compositions to illuminate stages of the composer’s life, and his relationships with various males, his pro-forma marriage to Antonina Miliukova, his 13-year relationship with the Countess Nadezhda von Meck, and his often spiky relationships with fellow composers (and pianists) Anton and Nikolai Rubenstein. Felder weaves into the narrative extended selection from works including Piano Concerto 1 (a disastrous premiere); Symphonies 4, 5 and 6; the 1812 Overture (he detested it); The Nutcracker (not a favorite as well) and other selections.

The tone of Our Great Tchaikovsky falls somewhere between confessional and entertainment, the artist as raconteur. This approach is somewhat at odds with what many historians would classify as Tchaikovsky’s introverted and often tormented personality: regaling an audience was not his forte. Nor does Felder delve deep into Tchaikovsky’s inner demons: they are more discussed than embodied. But Felder’s easy charisma and his masterful musical interpretations compensate more than adequately for his re-imagining of Tchaikovsky, though his broad Russian accent and occasionally fey mannerisms verge on caricature at times.

Felder also designed the set, a real standout in the production. A piano dominates center stage, as would be expected, flanked to the left and right by small tables, one stage right with a samovar. Birch trees in the near background provide the countryside atmosphere of his dacha outside Moscow. But his use of projected images on a cyclorama at the back of the shallow stage proves to be an artistic masterstroke -- moving, animated images, often in the style of Russian artists such as Chagall, Serov, Repin, and Kandinsky, with scenes of Russian winter, St. Basil’s Cathedral, and other places evocative of late 19th-century Tsarist Russia. Director Trevor Hay, at the helm for most of Felder’s other shows and of 23 seasons’ worth of shows at the Old Globe in San Diego, keeps a steady hand on the proceedings.

Felder’s invitation by the Russian government in 2014 to perform Our Great Tchaikovsky in Russia—and his decision not to go—is interwoven into the narrative of the show. Present-day Russia has reverted to the morality of Tsarist days, as Felder reminds the audience, despite the promise of glasnost. One can only wonder what might happen to Tchaikovsky in the Russia of today.

Performances of Our Great Tchaikovsky continue at the Mountain View Center for the Performing Arts through February 11th. For more information visit: https://theatreworks.org/