Did the 21st anniversary of the Rwandan massacre kick-start the idea to write about it or has the story been preying on your mind since 1994?

I first started the idea for this play back in 2001 when I read Philip Gourevitch's book about the Rwandan genocide. I knew the basic details, but it was only once learning about the Catholic Church's involvement that I really started thinking about turning this into a play. So it was reading that book and then also trying to follow the trial of what the press were calling the killer nuns of Rwanda who were about to stand trial for crimes against humanity for their perceived role in the church massacre. It took me a long time to get the initial draft of the play out. I was overwhelmed by research so for the first four or five years, I did a ton of research about Rwanda, about the Catholic Church in Rwanda, about the genocide. It's almost a coincidence that these two productions in London and in New York are happening at the twenty-first anniversary.

What do you remember of the 1994 news coverage?

I remember reading about it in the newspaper and seeing a story about it on the news with very minimal coverage. It made it seem like it was part of a war. I went back, preparing for this production to the first reports in the New York Times and it was all about – there's a war in Rwanda between the RPF (Rwandan Patriotic Front) and the government and so the idea that it was a full-on genocide took a long time for the American press to report. It was only after reading Philip Gourevitch's book and then doing research, that I realized the great Irish and English reporters who were covering the genocide in great detail.

Not intentionally. I started writing this play before I made a movie. The film that I wrote was actually the adaptation of a play in both instances and so I imagine the play being done in a very stripped down simple way where sound would really help us figure out the location. But yeah, I guess our production here has a very cinematic feel. It's almost like cross-cuts where the scenes overlap a little bit. It wasn't intentional. I think it's definitely a play insofar as what theater can do is different than what film can do. I think maybe film can show the details of the genocide more clearly but the emotional resonance is stronger in a play.

You recently premiered your play in London. How was the response and thus far, how does it compare with New York audiences?

In London, there were a couple of performances I was at where people didn't clap at the end, and we were all a little worried, and then I realized that people were just really moved. (Laughs) The English are obviously not comfortable showing their feelings in public, so there would just be utter stillness at the end of the play. I don't tend to read reviews but I know that they were all positive across the board in London. Reviews haven't started coming out here so I don't know. All I know is from the people I've talked to who've seen the play who've found it very moving and so that's been very gratifying. I go to all the previews and I take notes and then after the opening I might pop back in just to say goodbye to it, maybe at the very end, but after the opening I leave the actors alone so that they can make the show their own. I try not to interfere too much.

Is the interplay of religion themes in the play of specific interest to you?

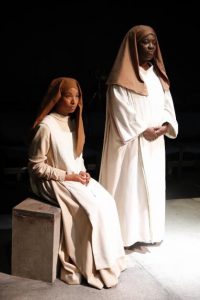

There was a play of mine done in New York in 2014 called The Correspondent that was also a little bit about religion. I was raised Catholic and I'm not a practicing Catholic anymore. I've run pretty far away from religion but I will say that that stuff stays with you. For a long time I didn't want to write about Catholicism. When I first started working on this play I thought that maybe I don't have to talk about Catholicism, even though my two primary characters were nuns (laughs) and then I realized I had to. My Catholic education kept coming back to me when I was doing the play and I became obsessed with the Stations of the Cross. I thought that would be a good model for the play in that when you follow the footsteps of Jesus, you radically identify with his suffering. When Dusabi tells his story when he and Elizabeth fled from the militia and ended up in the church, that sequence is some ways is loosely inspired by the Stations of the Cross.

Sense of an Endingdoes a very good job of filling in the complex background to a war that those under twenty-five might not be so familiar with. Sister Alice's dialogue informs us that the Hutus, in her eyes, had good cause for vengeance after after the way they were treated by Tutsis in previous decades. Do you hold the previous colonists accountable for much of the conflict?

Colonialism is hugely responsible for making what might have been slight tribal differences into ethnic differences in a kind of Western colonial model, but certainly that cycle of violence dates back centuries so what we see here is the eruption of that. Even now, you think of the current government there that's been in place since the end of the genocide in 1995 – it's quite repressive because people that oppose the government now, if they are on record for saying it they can be tried as a genocide denier, like being a Holocaust denier and then being thrown into jail with no trial. Amnesty International and other human rights organizations have been watching Rwanda because what used to be seen as a model case for democracy in Africa is now showing itself up to be much more complicated.

Do you think that there are latent resentments in all of humanity and when all is quiet, are those resentments merely lying dormant?

Well there's all those misreadings of Darwin, survival of the fittest, when actually Darwin is much more complicated than that. There's also all of those recent scientific studies that say that a large part of survival, is survival of the kindest. Those who are the most generous tend to be the ones that have the longest survival. On a good day, I would like to think that underneath all of humanity is a sense of empathy and kindness, but obviously so much of our history and current affairs proves otherwise, certainly in my country (laughs) as the recent presidential debates and campaigns show.

I made it up but I do remember someone telling me and reading in the Gourevitch book that reporters always said that Rwandans and Tutsis in particular have a very dark, bleak sense of humor, and so when I was working on the play, I had a couple of things that would guide me when I felt like I was getting off track. I knew that this would be a pretty intense play and it was giving me nightmares when I was working on it and so I said, I'm gonna make sure that there's three jokes in the play. That way there would be a little bit of comic relief. I don't know how much comic relief Paul's joke is but I didn't make it up from scratch. There was a moment when I had done so much research that I felt really overwhelmed by it and I put all the research away and instead I would just watch a video over and over of a survivor who had lost her hands in the genocide, until it physically affected me and I started to feel sick. Then I would work on the play. I could only do this a couple of times before I started to get ill and I had to stop doing that. I felt that was a way to connect with the material. A play that comes out a lot of research can start to feel like a thesis or a dissertation. I've never been a huge fan of documentary plays. I'm sure that at some point I read a whole lot of African jokes and then came up with my own version.

How closely did you work with director Adam Fitzgerald? Did his interpretation of your writing surprise you in any way?

I always work pretty closely with the directors for both the London production and the one here. I'll be in rehearsal a fair amount but I'll give them space to play. I'd worked with Adam before so I trusted him and I knew his style and we'd worked together on a play in the same space. We had a shared vocabulary of trust, but I think the thing I love about Adam is that it's always the best ideas that people go with, so we were very honest with each other about the work. I'm very surprised because it does feel like a very different production from the British production, the sense of space. It's up to the directors and the designers to figure out how the play looks and how it sounds. There were no church doors in the British production, and to Adam it was very important that those church doors are an omnipresent set piece and I thought that sounded really interesting.

The pauses, interruptions and overlapping of your dialogue are refreshingly different from many other theater pieces. How important is it for you to sound real at the risk of the loss of the occasional word?

I hear my plays before I see them. I'm a musician so I really obsess about the sound of my plays, the rhythm of it. So all of the overlapping dialogue and cut-off speech is written into the play because I really feel like I understand who a character is by the way he or she speaks. I do think the language is realistic but I also think there's a musicality to it. The play should sing as well as just be spoken. It's something I think a lot about as a writer. The way to the emotion or understanding of a character comes from the music of how they speak, so sometimes that sounds pretty realistic, but also in this play there are moments that are heightened and it sounds poetic.

What next for Ken Urban?

It's been a busy year which is good. I'm working on a couple of new projects and then The Awake which premiered here in this theater in 2013 will have a production in Chicago. I'm very excited about that as it'll be the first time I've seen it in a new venue with a different director. I have no doubt that it will be really different. And then we're workshopping a new play that's loosely based on the rise of violence against gay men and women in Uganda. I've done some interviews with people who work with Doctors Without Borders and that had a workshop in Boston and it'll have a workshop at the Playwrights' Center in Minneapolis in the spring. A lot of projects that I've been working on for a long time are starting to finish.