Michael McKeever’s new play Daniel’s Husband tackles the issue of marriage by taking a relationship to the worst-case scenario, exploring what happens when tragedy befalls a couple married in all senses but the legal (which, as it turns out, is an important aspect of it all). Daniel (Ryan Spahn) longs to marry his boyfriend, but Mitchell (Matthew Montelongo) resists the idea of marriage, since he’s a staunch believer that it adds nothing to a relationship. He believes that right up until Daniel suffers a stroke, leaving him with locked-in syndrome and a battle for who should care for him – one in which he cannot speak.

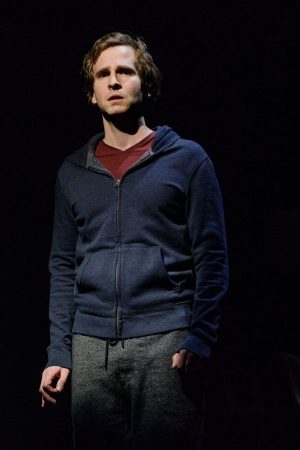

We spoke to Ryan Spahn, who plays Daniel, about what it was like to approach a role with such a challenging form of heartbreak and loss.

What drew you to this play and to this character?

Joe Brancato [the director] approached me about the play in the fall. He had seen me in a play called Exit Strategy, and prior to that conversation, I didn’t know that it was coming to Primary Stages (the company behind this production of Daniel’s Husband). I was really drawn to the argument of the play, and particularly the dilemma that children face when they want to break free of the legal ties of their parents, which I think is a big part of growing up. I think you’re sort of owned by your parents until you’re not anymore, and that’s a very important distinction when it comes to marriage. The play really highlights this really beautiful relationship between two people, and that you should never leave a room on an argument because you never know what’s going to happen.

I think the thought of doing an ensemble play, I’m really a fan of that. Mitchell is clearly the central character, but I think the ensemble shines in different places because different character has their moment to take the stage. That’s a significant part of a good and well-structured play.

Your character ultimately faces locked-in syndrome. How did you prepare for and approach that life changing scene?

I watched this film called The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. It’s an amazing film about a guy who gets what my character has, called locked-in syndrome, and has the scene where he has the stroke, driving with his son in the car. It’s a true story, and the guy wrote an entire memoir by blinking the alphabet to his nurse. It’s a true account of what it feels like for him, to be stuck inside of himself. The book was published, and the day the book was published he died. That book was made into a film, and that film [was nominated for] best foreign film Oscar.

Then I looked at a lot of photos of people who are going through this condition, and I watched videos of people talking about their loved ones or sitting next to somebody who is in that condition. You can see how that person behaves when someone is talking with them or about them. It’s a tricky one because they’re so still, and that’s just the only constant is that they’re completely frozen.

It’s funny, I’ve done a string of plays where something traumatic happens, if not I flat out die. My mom said “Ryan, I don’t think I can watch you die in another play.” And I was like, well I don’t technically die [in this play], but it might actually be worse than death, so I don’t think you should come see it. She actually hasn’t been to see it, because I think she would have a really rough time with it. Not because it’s not good, but just because of what the whole thing goes through.

Because of that unforeseeable twist of fate, the tone of the first and second halves of the play are quite different. What was it like to work with that transition?

Something that was important to me, and I know I brought it up in rehearsal a lot, because I did this play a couple of years ago in the city called Gloria, which had a massive incident occur about 50 minutes in that just shattered the entire tone of the play. I remember from that experience learning how important it was to, yes, keep the tone different, but make sure that the tone feels within the same world as the rest of the play. What could be the trap of doing scene one and scene two is that you push too far into almost sitcom in the first half, which is a style, and could be the style of the entire play, and that could be a delightful style, but it has to be so grounded in realism because the rest of the play is. You don’t want to feel like you’re tricking the audience into thinking that they’re seeing one thing, because then you’ll push people away. I think that we’ve been successful at keeping it funny and light, yet the characters feel like they’re the same people from scene one to scene six, even if you’re seeing slices of joy and then slices of heartbreak.

The parallel between the opening scene and the flashback in the last scene really helped with that cohesion.

Yeah! In the flashback scene of the date, there are obviously conversation points that we’ve talked about, that the audience can feel. More than that, it’s been really nice and fulfilling for both Matthew [Montelongo, who plays Mitchell] and I to feel them recognizing personality traits that they’ve learned about us. I’m a character who’s very Type A, and particular and specific and confident. They say all these things about me that you’ve witnessed through the play. So then when there’s moments in that final flashback scene where I’m saying things like “of course I know you want to get in this bathtub with me,” or “of course you like me, I mean look at me.” There’s things I do in that scene that, when they land, it’s really satisfying to Matthew and I because then we know that we’ve communicated those relationship dynamics early on so that when they hit in that scene the audience feels like they’re in on it.

The play obviously focuses a lot on marriage, and what it adds to a relationship. What do you think it ultimately decides about it?

There’s so many different ways to look at marriage, and most of society I would say looks at it as a shared love between two people, often in the eyes of God or the Church or things like that. It’s a real and beautiful thing for a lot of people. I’m not saying that’s not right. I just think there’s also the simple legalities of it, particularly when, the most part, if something was to go wrong you are legally bound to your parents. As grown people who are in committed, long relationships, you’re doing yourself and your partner and potentially your parents a massive disservice by not acknowledging that as a separate thing. If you don’t want to stand in front of everyone that’s one thing, but the legal side of it – it’s almost like dying without a will. You’re just subjecting a lot of people to clean up after you if you don’t take care of things like that. When marriage becomes a conversation, usually it’s the anxiety of being ready to do that, but then it starts to flip into “well, okay, we live in the same house, we share bank accounts” – there’s things that start coming up where you can’t ignore the importance and the relevance.