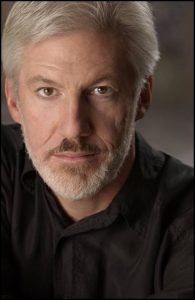

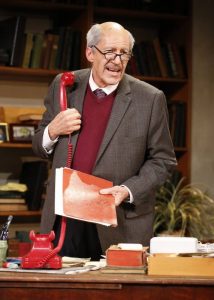

Tom Dugan is a playwright and actor who is currently starring in Wiesenthal at Theatre Row at the Acorn Theatre. The play tells the story of Simon Wiesenthal, who brought 1,100 Nazi war criminals to justice. In our interview, Mr. Dugan talks about Simon Wiesenthal, how we must present history to the next generation, and his next project.

Tell us a bit about Simon Wiesenthal. We know he brought 1,100 Nazi war criminals to justice…

Simon Wiesenthal was born in 1908, and studied architecture in Poland. By the time WWII and all the trouble in Europe came around, he was well into his thirties. He had lived a full life, and had learned a thing or about how to survive in the world. By the time the Holocaust came, he lost all his relatives in concentration camps. After WWII ended, he saw that a great mistake was about to be made—with every great war, they look at the war crimes, and then society would say “It was war—people do ugly things in war. Let’s forget it and move forth.” Wiesenthal wanted to prompt a teeny little growth spurt in mankind—a progress in man’s self-awareness, which is that humanity has, within it, the human savage, and we must own it and recognize it. That’s the only way that we can decide what is appropriate and acceptable in war, and what isn’t. So you get the war crimes tribunals, you get The Hague, you get all these mechanisms that are put into place after war. But you can take all that stuff to Wiesenthal’s work. He forced humanity to confront war crimes, and educated people about them with the help of Rabbi Marvin Hier (who founded the Wiesenthal center), which is heroic.

How did you come to know his story, and what about Wiesenthal’s story motivated you to adapt it for the stage?

My father was a decorated WWII veteran. He received a Bronze Battle Star and a Purple Heart, and he carried shrapnel in his hip. He also liberated some of the Buchenwald concentration camps. One day, I said to him, “You must really hate Germans.” He replied, “No. I don’t judge people by their backgrounds. I judge them by how they behave.” I was eight, so I didn’t quite get this—in the schoolyards, you hate the bully. When Wiesenthal passed away in 2005, I read his obituary. It described his rejection of collective guilt, which really piqued my curiosity and led me to read more about Wiesenthal’s life. Interesting side bar -- I’m not Jewish, I’m Catholic. And years later, I married a Jewish woman and how we have two Jewish boys. My father’s experience, his place in Jewish history, and my current life in the Jewish world, makes me very comfortable with telling this story.

What’s an example of some of Wiesenthal’s techniques in finding the Nazi war criminals?

There is a photo from the 1970s in Brazil of a funeral for one of the higher ups in the Nazi regime. All of his cronies came out to the funeral to honor him, and in the photo half a dozen men are doing the Hail Hitler salute as the coffin is lowered into the ground. Wiesenthal doesn’t recognize any of the people—so he names someone he really wants to find, and announces that the Nazi in the middle of the photograph, is that guy. It becomes front page news, and everyone’s looking for this guy, but it turns out it was complete baloney—all Wiesenthal did was point to one face and say this was him—so the guy in the picture has to come forward, say he isn’t him, and then he’s arrested.

There has been some controversy about Wiesenthal exaggerating his role in the Nazi-hunting that took place after the Holocaust.

Well in the 1950s, when he started his work, he was a novice with publicity, and so he didn’t think the stories were sexy enough to tell, so he shaved off the rough edges, and simplified the story so that it was palatable enough for the media to run it. He learned not to do that pretty quickly, because people would point at him and call him a liar. Holocaust deniers and extreme anti-Semites point to some of the exaggerations he made to debunk his work and call him a fraud. Also, people got mad that he said he knew for sure that Josef Mengele was alive in Brazil when in reality, he had died ten years before. So a lot of people said, “You were wrong!” But you know what? Thank God he was looking! He kept the trail hot for years. He threw out a large net, and he was criticized for it.

What do you hope people will learn from his story?

It’s the practicalities—that love is work. The play is NOT a stance memoir—it’s a spy thriller. The audience is very much a part of the show. In the play, he’s talking to a group of students in the Vienna Documentation Center. While he’s telling his story, he’s hunting down the highest ranking Nazi officials who are still living. The play takes place in 2003 when he’s hunting for Alois Brunner. During the play, the audience follows him in piecing the evidence, and wonder how he’s going to find this guy, hoping that when the phone rings next, they get closer to catching this guy. It’s quite exciting in the way he tricks people on the phone to get information, and the guy is an entertaining individual with a great sense of humor, so the audience spends half the time laughing.

What sort of research do you do for your plays, particularly Wiesenthal?

For Wiesenthal, I read three dozen books, all the documentaries I could find, and spoke to dozens of Holocaust survivors. What struck me about these conversations was that they were talking about some of the most horrible stories you could imagine, and they spoke very matter-of-factly. It left me as an actor to avoid all the melodrama that is the trap for an actor playing such a dramatic life, and I’m happy to say that I’ve had a hundred Holocaust survivors see the show. They all give it the thumbs up. The potential harm is that if the story is told badly, it will turn off the next generation to learn the lessons that have been learned. This story has to be told in a way young people want to hear. My favorite review that I’ve ever received came from a 15-year-old kid. I’ll do a talkback after the show, and this 15-year-old kid raised his hand, and gave a comment: “Wow I thought this was gonna suck.” He thought it was gonna suck! He probably thought, “Holocaust play, this is gonna be a good time." And it turns out it is!

Do you have any historical characters in mind you’d like to portray in the future?

Oh, yeah. I haven’t been writing anything for myself to perform in. I just wrote and premiered The Ghosts of Mary Lincoln in Georgia, and that play is planning a tour in the spring, and we’re very excited about that. And then I’m in the process of writing a one-woman show about Jackie Kennedy, which I’ll be writing it here in Manhattan.

Wiesenthal is now playing at the Acorn Theater at Theater Row, 410 West 42nd Street, New York, NY. For more information and tickets, visit https://www.wiesenthaltheplay.com/