Watching Arthur Miller's Incident at Vichy, directed by Michael Wilson and presented by the Signature Theatre as part of a celebration of the playwright's centennial, I wondered if it was the play's prescience - and the ease at which one unavoidably grafts the problems of our modern day onto an older work - that packed the house and pushed the production into an extended run. But walking out of the theater, forced into contemplative silence with the rest of the theatergoers, I realized that rather it is the unchanging universal truths that Miller exposed when he penned the play in 1964, which, like an uninterrupted hour of picking at an unhealed scab of the human condition, give the play its stomach-turning power.

In Vichy, France during the height of World War II, a group of men find themselves suddenly detained in a makeshift police station. As they’re called in to speak with the German and French officers one by one, the men slowly begin to pool their knowledge in an effort to determine why they've been arrested and what fate might await them. Proving himself worthy of his Pulitzer, Miller uses this rather simple conceit as a jumping off point for a lofty, feverish debate between several ideologies on matters ranging from politics to the essence of humanity and personhood.

Miller creates as broad a cross section of citizens as he can in an effort to demonstrate their varying viewpoints: an artist, a psychologist, a waiter, a railroad engineer, an actor, a young boy, a gypsy, an Austrian Royal. Each approaches their capture in a different way, some casting blame at their captors, others casting blame at the reasons they were captured, others firmly in denial about the gravity of their situation.

Why did I choose today to go outside? Why didn’t my mother let us leave the country when we had the chance, muses the panicky, pestering artist, played with jittery agitation by Jonny Orsini. The waiter (David Abeles) is in denial — he serves the commander breakfast, how could he be taken? -- as is the actor, played masterfully by Derek Smith, who knows how to project courage but little about living it. “I go under the assumption that if I obey the law I will live in peace,” he tells the rest.

The men grow increasingly fearful by the swirl of information whispered, rumored, or withheld altogether, and terror ekes out like battery acid; the socialist leaning engineer (Alex Morf) admits that he's seen people being transported in locked railcars, the waiter tells of rumored furnaces in Poland, and could the officers possibly be inspecting for circumcision?

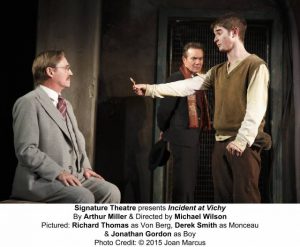

The play holds stormily at its heart the famous quote by Edmund Burke, "The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing." Von Berg, played by Richard Thomas, is an Austrian aristocrat, desperate to distance himself from the horrors of the Nazis, yet undoubtedly safe from their wrath, unlike the rest of the men with whom he shares a cell. On the other side of the interrogation table, a Major (James Carpinello) reasons his way through his abhorrent task with bone-chilling bureaucratic aplomb: I’m simply following orders, someone else will just take my place if I refuse.

The play holds stormily at its heart the famous quote by Edmund Burke, "The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing." Von Berg, played by Richard Thomas, is an Austrian aristocrat, desperate to distance himself from the horrors of the Nazis, yet undoubtedly safe from their wrath, unlike the rest of the men with whom he shares a cell. On the other side of the interrogation table, a Major (James Carpinello) reasons his way through his abhorrent task with bone-chilling bureaucratic aplomb: I’m simply following orders, someone else will just take my place if I refuse.

Some of the play’s most powerful moments lie in the stony silence, when the men sit immersed in the torturous paradox of their situation, wondering if a surer death awaits them if they try to escape or if they resign themselves and walk through the doors of the interrogation room, from which none of the men seem to be exiting.

In the span of the play’s one act, Miller doesn't quite have the time to develop the characters subtly, and relies on easy jokes and caricatured revelation. And perhaps the play might have been better served in a more intimate theater space, where the urgency of the action would have been felt all the more. Instead, the actors are left to traipse back and forth across the stage, and some of the performances even border dangerously on camp, such as the staccato, old Hollywood delivery by Darren Pettie as the psychologist.

But ultimately, though the play might seem at times a little dusty and stiff for contemporary audiences, in an age of Twitter activism and unity via Facebook, it's important to refresh ourselves on the unspeakable atrocities that can happen and will continue to happen if the privileged don’t truly act on behalf of the persecuted. In Incident At Vichy, Miller wants each and every theatergoer to ask oneself: how much are you willing to sacrifice to stop something you know is wrong, and will you make that sacrifice before it's too late?