In advance of the April 18 premiere of Indecent at Broadway’s Cort Theater, Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Paula Vogel spoke to the New York Times about her long-overdue debut on the Great White Way. “You feel the ghosts in a really great way,” she remarked, “and they’re the kind of ghosts that are saying, ‘Welcome home.’”

It’s a fitting quote, because Indecent, written by Vogel and co-created with director Rebecca Taichman, is a play about restless ghosts of the theater-past, ghosts which spoke to Vogel across generations, and which she is in a unique position of vindicating in this engaging, heartfelt work.

Indecent, which first premiered in 2015 at Yale Repertory, is a metatheatrical reworking of Sholem Asch's 1906 play God of Vengeance — a controversial yet critical part of the Yiddish theatrical canon — that received acclaim both internationally and its first American run in Greenwich Village, finally making it to Broadway’s Apollo Theater in 1923. Despite the removal of a key love scene between two women, Rivkele, a young Jewish girl, and Manke, a slightly older prostitute in Rivkele’s father's employ, the play was deemed too scandalous for uptown crowds; after all, the play still featured Broadway’s first lesbian kiss. Within weeks, the production was shut down, the producer and cast jailed for obscenity.

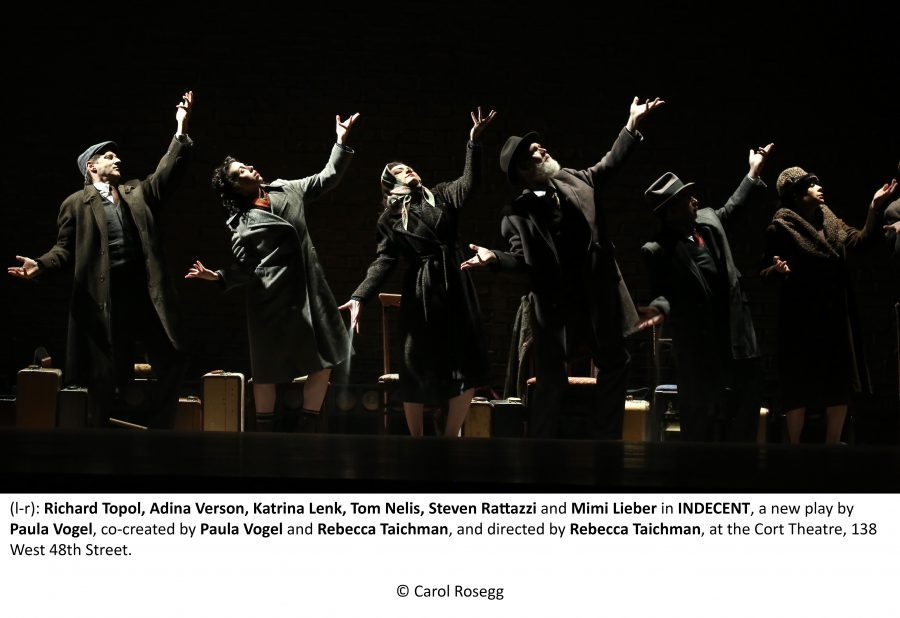

Rising from dust of history, Lemml (played by Richard Topol), the genial stagemanager and, as we learn in an early vignette, the play’s first and most fervent champion, calls his troupe to order and leads them through a whirlwind series of vignettes that recreate the life of the play as it spanned the globe in the first half of the 20th century.

In many ways, Indecent is perfectly suited for Broadway. Though the set design is minimal, subtitles projected against the brick backdrop help anchor us in place, time and language. As three onstage musicians —Gutkin, Halva and Matt Darriau — provide a raucous, klezmer-centric score, David Dorfman’s mesmerizing choreography propels the action, the actors expanding to the larger space easily. The troupe moves as a seamless mechanism, fitting perfectly together like gears of a clock, to conjure both the beauty and pain of time.

Though not strictly a musical, punchy, full-troupe song and dance numbers lightheartedly poke at the play's larger, more serious themes. (A Berlin cabaret number winks at liberal gender expression. Later, as transplants to a sometimes hostile new world, the actors yank off their payot with a shrug, singing, "What Can You Do? It's America.")

And yet, the play is still more cerebral than most that make it to Broadway, and you have to pay close attention to keep up, as it races through time, uninterrupted by an intermission. As (among other characters) Manke and Rivkele, Katrina Lenk and Adina Verson conjure the love that proved so controversial and which drew Vogel to the work. As young through middle-aged Sholem Asche, Max Gordon Moore captures the spirit of an artist whose work escapes his ownership to become something much larger.

Vogel and Taichman’s ambitious play within a play creeps unstoppably towards the horrors of the Holocaust as it wrestles with such heavy themes as censorship, homophobia, antisemitism and xenophobia, parsing the ways we forge our identity in an ever-changing world. It’s a remarkable feat, then, that the play isn’t mired in gloom. On the contrary, Vogel, Taichman, composers Gutkin and Halva, choreographer Dorfman and their stellar cast have crafted an exuberant, exciting show, one which exudes warmth and is, above all, a testament to the transportive, life-affirming power of theater.