The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, a book by the neurologist Oliver Sacks about his patients case histories, contains stories so remarkable that they far surpass the fantasies of fiction. The Valley of Astonishment, written and directed by Peter Brook and Marie-Hélène Estienne, is in part inspired by Dr. Sacks' work; presented by Theatre for a New Audience at the beautiful new Polonsky Shakespeare Center, it is a dizzying exploration into to the possibilities of the human mind, woven lyrically around Farid Attar's poem "The Conference of the Birds" and the live music of Raphael Chambouvet and Toshi Tsuchitori.

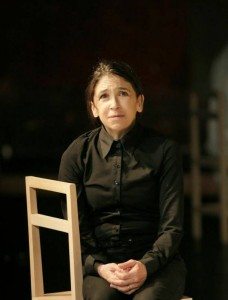

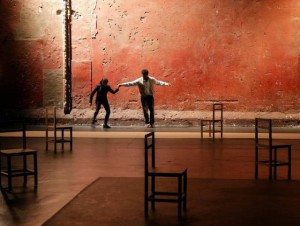

In the same sweeping breath, the play's three actors, perched on plain wooden chairs, tell the story of the a mythical animal, the Phoenix, and how it lives and dies in a regenerative cycle; then one, the transfixing and fearless Kathryn Hunter, becomes Mrs. Samy Costas, launching into a story that, if fiction, is mesmerizing in its humanity and believability. Loosely set around the Center for Neurological Research, as the play unfolds two patient and kind scientists guide Costas and a few other "subjects" through descriptions of certain events in their lives, helping them to map the brilliance of their unusual brains into colorful reenactments on the blank canvas of the stage.

The play dwells in a succulent ambiguity akin to what Dr. Sacks' book suggests: that life can indeed be stranger than fiction. Of the cases that unfold, most involve people with synesthesia, which causes two or more of the senses to become mixed. In one vivid moment, a young man, played tenderly by Jared McNeill, shows us how he would paint the colors he saw when he listened to jazz music on large sheets stretched across the floor of his garage. Samy in turn tells us that one key to her miraculous memory lies in creating elaborate pictorial associations with words and numbers. To her, the number 78 presents in her brain as a tall, mustachioed man (7) flirting with a fat lady (8). There is certainly humor in these fantastic revelations, as well as sorrow. The young man never reveals the unusual inspiration behind his paintings for fear of being labeled a freak; Samy is besieged and overwhelmed by the weight of her endless memory.

The play dwells in a succulent ambiguity akin to what Dr. Sacks' book suggests: that life can indeed be stranger than fiction. Of the cases that unfold, most involve people with synesthesia, which causes two or more of the senses to become mixed. In one vivid moment, a young man, played tenderly by Jared McNeill, shows us how he would paint the colors he saw when he listened to jazz music on large sheets stretched across the floor of his garage. Samy in turn tells us that one key to her miraculous memory lies in creating elaborate pictorial associations with words and numbers. To her, the number 78 presents in her brain as a tall, mustachioed man (7) flirting with a fat lady (8). There is certainly humor in these fantastic revelations, as well as sorrow. The young man never reveals the unusual inspiration behind his paintings for fear of being labeled a freak; Samy is besieged and overwhelmed by the weight of her endless memory.

Approaching these stories through the lens of science, we enter a curious territory of observation and diagnosis. Valley highlights this, reminding us that we have an intense desire as human beings to see things in groups, define things through their opposites, label them so we can put them in categories. This play recognizes that desire, and dwells in the potential happiness that can bring. We understand Mrs. Costas' initial joy when she is "discovered" as a phenomenon, and other subjects who share their stories seem so thrilled to be given a label and finally understand themselves as part of a larger whole, a group to which they belong. But where the play displays its genius is in pushing us far beyond this settling moment of comfort and belonging, and also exploring the danger of labels, the danger of seeing things as ordinary or extraordinary, normal or deviant.

The play doesn't concern itself with clear distinctions between fact or fiction, fantasy or reality, pleasure or pain, joy or sadness, because in The Valley of Astonishment, in the human experience, all of these things are possible. Aside from a modern style of dress, the occasional modern pop cultural reference (Uma Thurman comes up somewhere), and mentions of New York City addresses, the play, with its sparsely decorated stage, has a remarkable timelessness and universality, and the trio of actors, Hunter, McNeilll, and Marcello Magni, become scientists, subjects, editors, magicians, without changing much of their original speaking patterns or affects. They masterfully embody the variety of roles they take on, but ultimately they are actors, storytellers, who serve to remind us that in the theatre, deviance is not only accepted, but embraced, and, above all else, no mater how astonishing, we all must help to tell each other's stories.

The play doesn't concern itself with clear distinctions between fact or fiction, fantasy or reality, pleasure or pain, joy or sadness, because in The Valley of Astonishment, in the human experience, all of these things are possible. Aside from a modern style of dress, the occasional modern pop cultural reference (Uma Thurman comes up somewhere), and mentions of New York City addresses, the play, with its sparsely decorated stage, has a remarkable timelessness and universality, and the trio of actors, Hunter, McNeilll, and Marcello Magni, become scientists, subjects, editors, magicians, without changing much of their original speaking patterns or affects. They masterfully embody the variety of roles they take on, but ultimately they are actors, storytellers, who serve to remind us that in the theatre, deviance is not only accepted, but embraced, and, above all else, no mater how astonishing, we all must help to tell each other's stories.

The Valley of Astonishment continues its run at the Polonsky Shakespeare Center through October 5. More more information and tickets, visit https://www.tfana.org/

At the Polonsky Shakespeare Center through October 5.