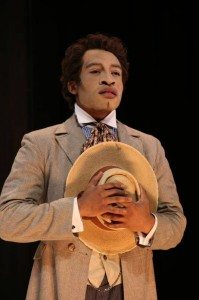

For his theatrical debut in New York City, Austin Smith is hitting the ground running in a big way. His lead role in An Octoroon at Theatre for a New Audience encompasses not one but three characters, including a portrayal of the playwright, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, as well as both the dashing hero and the comic villain of Jacobs-Jenkins's play-within-a-play adaptation of Dion Boucicault's 1859 melodrama, The Octoroon. In case that wasn't enough of a challenge for the recent graduate of Juilliard, his predecessor, who embodied the role during the sold-old debut of the show at Soho Rep in 2014, took home an Obie award for best actor. The talented young actor, however, seems to be taking it all in stride. And when I caught up with him on his day off, he assured me it was all in a day's work. If you're great at your job, perhaps.

This is a very historically laden play, what did you do to prepare? Did you do any research or read the original Octoroon?

For the show I initially did not read the original, because I wanted to approach it in the same way that I would as an audience member of the show if that makes sense, someone experiencing the world through Branden’s eyes. Especially because so much of the plot is in Branden’s version. And I don’t know, that wasn’t initially my way in. And I guess it’s because the part wants to be worked from the outside in. I felt like everything I needed was on the page, so I didn’t initially go to the original. Since then I have looked at it. I read Branden’s adaptation over and over and over again and really tried to familiarize myself with the style more than anything else in terms of the performance of it. I watched a lot of clips of Gone With the Wind. Things that would help me understand not only the style of performance, but to bring me back to that antebellum time; I felt that that was most important in terms of nailing the melodrama and I did some research in terms of the actual techniques or styles. Almost the gestural vocabulary of melodrama, which was helpful because Sarah [Benson, the director] was really interested in nailing down and working within the broad style of melodrama, so that was my first concern.

Beyond the challenge, obviously, of playing three different roles, you are also, as you said, balancing between melodramatic characters and hyper-realism in other moments. You mentioned drawing from old melodramas, but I'm wondering what it was like for you being an actor coming recently out of formal training to switch between such different styles of acting?

Initially it was difficult, because the parts of the play that we in the twenty-first century recognize as psychological realism, those parts feel like home, and those parts feel honest. But the melodrama seems hard, because you worry that this extreme emotion will read as phony or as outlandish or fake. You have to trust that the further you go with the melodrama the more that the other scenes will actually land and the play as a whole will work. But it was hard to trust that, cause it does feel almost like you're outside of your body in a way that you don't want to be as an actor. The more you do it and the more you acclimate your body to what it's having to express -- the larger-than-life emotions with these grand gestures -- over time in rehearsal you get used to it. But it was definitely a little jarring, especially because a lot of the stuff I had worked on leading up to this was more like naturalism.

Another question along the lines of contrast. The play is hilarious, but there's definitely a point where you have to stop laughing. As a lead actor, how do you feel about finding that line? What do you expect or hope for from the audience and how you feel about treating those heavier subject matters - such as slavery - with humor?

I think that more often than not irony and humor are our best weapons in combating things that we find to be unjust, or to deal with things that we don't otherwise know how to talk about or else it would be almost too painful. I think that many comedians would agree. A lot of people say that comedy is tragedy plus time or tragedy plus distance, so I think that's definitely at play.

I also think that the genius of the play is that Branden is so ahead of his time. I can't quite wrap my mind around his genius, but what is so astounding about the play is that in many ways the play in and of itself is so self-referential, and I think that what the audience experiences, or at least I hope what they experience, and what we're starting to feel that they're experiencing, is that you do laugh, a lot, and especially at the slaves, because there are scenes not just because they're slaves... you overhear any conversation between two coworkers where they're discussing their boss's penis and that would be hilarious. But in this situation it's two slaves. Over the course of the play the audience is laughing, and there are moments that are so strategically placed where I think the audience can't laugh. Like when at the end Dido [a slave] says, "I just don't know what I'm supposed to be doing better." I think the audience is in some ways blindsided, because those are the characters that they've been laughing at the whole time, and then when they can't laugh, it forces them to consider, "ooh, I've been laughing at this." And should I have been? And I don't think there's necessarily an answer to that, but the play allows people to have that moment of recognition to then question their own complex feelings about history and slavery and our messed up American identity.

[There are some scenes where] I experience the audience laughing at moments where I never would have expected them to laugh. But thankfully Amber Gray [who portrays Zoe], who did the show at Soho Rep, she was like, "It's okay, just get used to it." So I think the solution, what you try to do as an actor is kind of play the moment with as much truth or intention as possible and ultimately the audience is gonna have the response they're gonna have, and you just have to do your best. The play does walk a fine line, cause I never would have referred to it as a full on comedy, but I've even heard Branden refer to it that way. So it does toe that line, but it does it in a way that's so useful, and really, I think the play works.

And the laughing makes the moments when all of a sudden you're not laughing all the more poignant.

Definitely, yeah.

You mention the more controversial elements of the play, and just to mention a few that you're directly involved in - partial nudity, cursing, whiteface. As an actor stepping into your first big role I wonder what the biggest challenge was for you?

Oh wow. Well, had you asked me this a week ago before we started tech, it probably would have been seeing my face in whiteface in the mirror at the beginning of the play. The first time we did it in rehearsal, I was like, oh brother. And you know the more you do it, the more you accept that that's part of the show. But then we got into tech, and the photograph that is projected during act four I've personally seen many times, but the first time we teched that scene, and we walked back out on stage and I saw it in a version that was like ten times the size of my body, that was like... Oh god. So I think there are certain things, certain rituals that we employ in the play - obviously the blackface, some of the language, and the fact that you end up forming what is essentially a huge lynch mob - I think when I start to consider those things in their actual context I get chills a little bit. Those are things that I think the play forces me to confront, but also allows me to deal with simply in the doing of the play.

I think being in a play as a black American actor that deals with all of these things -- but then dealing with it in a way from the other side, because I play two white men in the play -- that has been challenging, especially the first time we ran some of the scenes and two of my castmates who look like me are bowing to me and calling me Master George. But what you do as an actor is your body starts to take over and you just accept that this is the role in the play. I have to remind myself that what the audience is seeing, that in the moment I'm doing my best to embody this white romantic lead and this white comic villain, the audience is seeing this black man in white face. So you have to trust that the layers on which the play is working are working for the audience.

Did you find in your work so far as an actor that this play in particular really challenged you?

Yeah, well oddly enough the last play that I worked on at school had very racial undertones - I did "Master Harold"...and the Boys by Athol Fugard that takes place at the beginning of apartheid in South Africa. But I don't find that I'm encountering it in the same way, because Master Harold is a totally realistic play, so my experience was, 'Wow, this is what it felt like to be a black person in South Africa in 1951.' In this play I feel like my job is more so to distance myself enough from my feelings so that I can adequately tell this story so that the audience has the experience that they're supposed to have. And in that way the play is very Brechtian, I think, because if I get too wrapped up in my feelings as an African American male in the twenty-first centrury in this play, I don't do it justice. I think I have to approach it really from the sense of being a performer.

So you really turn yourself over to his words?

Exactly, yeah. In order for the huge machine that is An Octoroon to work and to, I think, have the effect that it should, I kind of have to appear not to be overly affected by it. Of course I am -- the first time I read the final act of the play I was almost in tears -- but all of the things that I have to do in the play, especially all of the things I have to do in Act Four, I really have to give over to the performative nature of it as opposed to any kind of psychological or emotional realism. Which is something that makes it work for the audience, that slight bit of separation.

Chris Meyers, your predecessor, won an Obie for his role, as I'm sure you're painfully aware. What was it like stepping into such big shoes? Did you resolve to make a distinctive mark on the character going into it?

You're right, I'm more than aware, and what's crazy is I'm actually - Chris and I both went to the same school, and I through mutual friends know Chris. Chris and I actually did a reading together while he was still doing An Octoroon, and I remember telling him that I was going to try my best to come, and at that point he hadn't won the Obie. And I remember saying, "that's so great, blah blah blah." But never in a million years did I think I'd be playing that part. So it's just so crazy that it's happening. Chris sent me a really nice message when they announced casting, and I jokingly told him I'd take care of his baby.

I knew that, and I did and I think I still am doing my best to relinquish myself of any expectation, because we're different people, so ultimately we're not going to do the same thing. It's kind of a given in the theater that you'll step into a role that someone else has done. So in a way it's great that I'm getting that experience now. What was so great is that I wasn't necessarily alone. Granted, I'm playing the lead guy, but six of the eight people were not in the production at Soho Rep, so I think we all felt like we really had the liberty and the permission to discover it for ourselves. I don't think I was out to necessarily put any distinctive mark on the role, partly because I know Branden and honestly if I get up and say the text, it's Branden and it will work. I want to push myself to go as far as I can and just do my best to tell this story and let the chips fall where they may. And I'm so grateful to Sarah and the entire team who really made me feel, again, as though I had the right to explore this for myself and kind of rediscover this part. This kind of reincarnation. It is nerve wracking, because you know that there were people coming back who saw it before, or who heard great things and are coming for the first time. And you know that the artistic team at a Theater for a New Audience saw it at Soho Rep, but they've all been incredibly supportive, and I feel safe to do the work that this play requires. People who have come to the previews have had great things to say, which is wonderful.

I'm trying to honor the text first and foremost, which is my job as an actor. And hopefully I get the job done.

An Octoroon is on stage at Theatre for a New Audience through March 8.