1. Oklahoma!

1. Oklahoma!

Something quite extraordinary took place over the summer at Bard College, where visionary director Daniel Fish took a 70 year old musical (the very first “groundbreaking” Broadway musical in fact) and turned it not only into something of the “now”, but also of the future. For as long as there have been musicals, Oklahoma! has been a staple of high school, non-professional and Broadway productions, but it’s become so familiar to audiences that it’s lost most of its power. How is it then, that Fish turned it into an indictment on contemporary xenophobia? Or a feminist call to action which not only gave female characters agency, but freed them from sexual taboos? Powered by astonishing performances by Damon Daunno and Amber Grey as Curly and Laurey, respectively, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s score has rarely sounded this urgent and provocative. When Allison Strong as Ado Annie sang “I Cain’t Say No”, it was as much about confusion and free-spiritedness. Every single character in Oklahoma! contained multitudes, and that Fish achieved this without taking away anything of what makes the show feel like comfort food was a revelation.

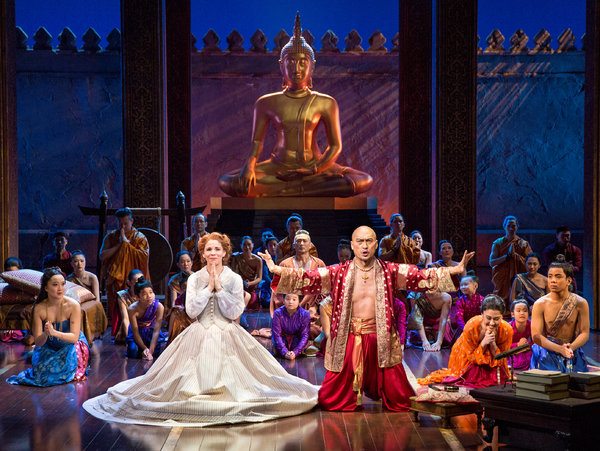

2. The King and I

2. The King and I

Sometimes too much of a good thing is precisely one what needs, and for all the majesty (a life-sized steamboat making its way across the fog onstage, columns and drapes as far as the eye can see!) and technical precision of Lincoln Center Theater’s production of the beloved Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, there was such a big heart at its center, that one wonders if the smiles and tears of audience members watching Kelli O’Hara as Anna Leonowens were being used as some sort of fuel to propel the staging. It was also quite an unexpected delight to see Bartlett Sher inject some sex into a 19th-century-set plot, with the mere thrust of a hip, and the suave placement of a hand on O’Hara’s waist during “Shall We Dance?”, Ken Watanabe’s King of Siam, triggered more erotic fantasies than anything out of the trashiest pulp could.

A house was certainly not a home in Mac Rogers’ ambitious sci-fi trilogy, which instead pondered on what happens to buildings once we no longer inhabit them, perhaps even, during a future where human presence itself would be rare. The building in question is the former house of a family that goes from being a traditional abode, to becoming a makeshift courtroom in a future where giant cockroach-like aliens have invaded the planet. Going from a domestic drama a powerful legal thriller, the trilogy was even more impressive when done over an 8-hour marathon, which for better or for worse, made the world seem like a completely different place upon leaving the theater.

It seems that a recurring theme in the plays and musicals of 2015, was reminding us what the theatre has to offer us that film and television can’t. For all the marvels of 3D, surround system and the ability to stream entertainment at our convenience, theatre still gives audience members a truly complete sensorial experience. In Stephen Daldry’s revival of David Hare’s Skylight, it was the smell of a bolognese sauce prepared by Kyra (Carey Mulligan) for her former lover Tom (Bill Nighy) that filled the air at the Golden Theater with a sense of melancholy that pierced the soul. As the two ex-lovers remember what drew them together, and eventually apart, we were pulled into a world where idealism and heartbreak live side by side. Mulligan, who evoked Kyra’s entire history simply by “being”, gave the performance of the year.

Bold, strangely beautiful, and often quite messy, Kander and Ebb’s last musical to hit Broadway underwent as many changes as its heroine had secrets (the decade-plus-long production history is worthy of a drama of its own). Chita Rivera starred as Claire Zachanassian, the world’s richest woman, whose homecoming, to the town that once sent her into exile, is not without its purpose. In order to reclaim her soul, her revenge will be to have the townspeople kill the man who broke her heart (played first by the late Roger Rees, and eventually by a haunting Tom Nelis), but at the center of the musical lies a philosophical question more striking than most musical theatre is allowed to ask: is she dead already? Unsentimental, chilling, dryly humorous and often majestic, The Visit was an expressionistic musical in the best Brechtian tradition. If cinema enfant terrible Lars Von Trier was ever tempted to adapt a Broadway musical into film, this would be his choice.

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins has earned a reputation for making theatre that slaps you out of your comfort zone, and while Gloria does contain a “twist”, more immediately visceral than almost anything else onstage in 2015, it also contains a zen-like mindfulness that pervades and transcends the brutality. Set within several workplaces (from actual offices, to a quiet Starbucks) the play looked at bureaucracy, professional ladder-climbing and the meaning of “success” through people who on the surface seem to lack any sensitivity. Never one to look down on them, or patronize, Jacobs-Jenkins instead allowed his characters to try and find their own salvation. More than a criticism of the detachment that comes with modern age, it was a plea to make real communication a priority.

Lois Smith commands the stage with grace and subtlety as Marjorie, an elderly widow trying to cope with loneliness with the help of a hologram shaped after her late husband. Marjorie is no angel though, and her hologram is a version of her husband at the prime of his beauty (played by Noah Bean) which makes for an interesting take on the things we keep, the memories we treasure. Elegant, precise and purposely pragmatic, Jordan Harrison’s beautiful prose allows for interpretations meant to evoke reactions from people coming from all walks of life. To some it will seem an eerie premonition of where the future might take us, while others will find comfort in the angelic quality of the holograms. Regardless of the first impression, Marjorie Prime, is a play to take away with you.

Nothing can prepare you for what waits on the other side of the wall in Rajiv Joseph’s Guards at the Taj. Set in 1648 India, it follows two Imperial guards (played wonderfully by Omar Metwally and Arian Moayed) over the course of the fateful night before the unveiling of the Taj Mahal, when they’re asked to perform a task that will change their lives forever. Brutal, but never exploitative, the play explored the concept of violence “with a purpose” and served as a mirror to our death-obsessed culture. What we saw might not have been what we wanted to, but Joseph offered an alternate reflection, one where beauty and the imagination co-exist in endless harmony.

Anna Ziegler’s intimate love triangle, dealt with memory in ways that often made it seem as if she was writing about you specifically. Set over one eventful Christmas eve, the play began with Sarah (Miriam Silverman) and her boyfriend Sam (Matt Dellapina) cozying on the couch, when they are interrupted by knocks at the door. Sarah, in retrospect, wonders if she should have bothered opening, one of the many questions that keep haunting her by the time we meet her. And it’s the “time” in question that Ms. Ziegler manipulates with absolute mastery, uninterested in traditional rules about establishing settings, she instead weaves a noir-ish labyrinth similar to the doubts and wishful thinking that often plague our mind. As the unexpected visitor, Nick Westrate, gave a manic performance reminiscent of the best work by Dean or Brando, it’s as if his heart will stop beating when he ceases moving.

Arthur Miller’s centennial was marked by celebrations in all shapes and forms, from the first Yiddish revival of Death of a Salesman to play in New York in almost five decades, to Signature Theatre’s exemplary production of Incident at Vichy. But no other Miller revival proved as effective as Ivo van Hove’s minimalist approach to A View from the Bridge, which saw Mark Strong deliver one of the finest performances of the decade as the tragic Eddie Carbone, a man whose downfall lies in his fierce belief in his convictions. Stripped of changing sets and period costumes, the play is set in what seems to be a boxing ring, or a fish tank, where all we are left with are Miller’s words, the deep humanism of the actors and van Hove’s nod to how the play’s ideas - essentially anti-migratory feelings in America - are sadly more relevant than ever.