In the stage directions for Big Love (at Signature Theatre) playwright Charles Mee remarks that the setting of the play is “more an installation than a set.” It may be right to view the entire play with that note in mind — to imagine the script as a kind of a blueprint for an elaborate performance-art piece in a museum or gallery. Mee and director Tina Landau have incorporated all sorts of bells and whistles to make their art pop. Austin Switser’s projections are extensive and nicely incorporated into the production. “Found” artifacts, including such familiar musical numbers as Leslie Gore’s "You Don’t Own Me” and Michael Jackson’s “Bad,” are pasted wittily into the collage. Mee’s primary recycled text, though, is an ancient one. Big Love is based on Aeschylus’ tragedy The Danaids, written circa 470 BC.

In the stage directions for Big Love (at Signature Theatre) playwright Charles Mee remarks that the setting of the play is “more an installation than a set.” It may be right to view the entire play with that note in mind — to imagine the script as a kind of a blueprint for an elaborate performance-art piece in a museum or gallery. Mee and director Tina Landau have incorporated all sorts of bells and whistles to make their art pop. Austin Switser’s projections are extensive and nicely incorporated into the production. “Found” artifacts, including such familiar musical numbers as Leslie Gore’s "You Don’t Own Me” and Michael Jackson’s “Bad,” are pasted wittily into the collage. Mee’s primary recycled text, though, is an ancient one. Big Love is based on Aeschylus’ tragedy The Danaids, written circa 470 BC.

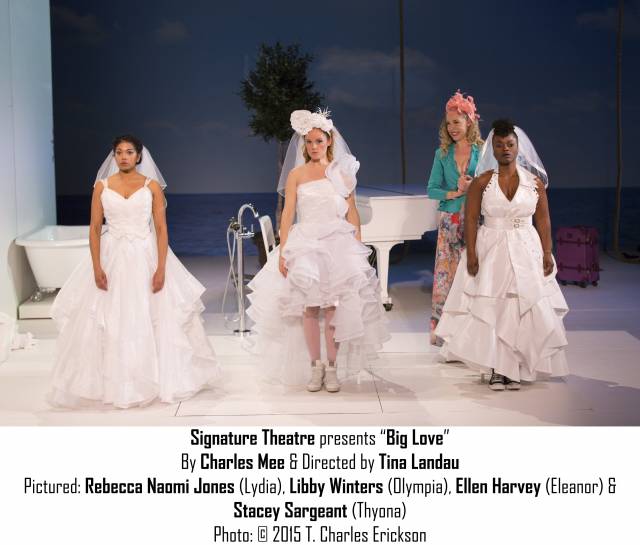

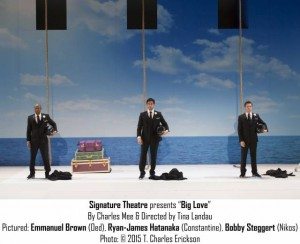

The play concerns fifty sisters who sail from Greece to Italy to escape their fate: a planned group marriage to an equally large number of male cousins. Mee focuses on three of these women. Thyona (Stacey Sargeant) is an angry radical feminist who views the upcoming mass marriage as synonymous with rape. Not so adamantly opposed to the nuptials are Olympia (Libby Winters) and Lydia (Rebecca Naomi Jones). In fact, after the disgruntled grooms are dropped by helicopter near the villa where the brides are hiding, Lydia begins to develop tender feelings for her intended spouse, Nikos (Bobby Steggert).

The designers here—Brett J. Banakis (scenic design), Anita Yavich (costumes), Scott Zielinski (lighting), and Kevin O’Donnell (sound)—have teamed with Mee, Landau, and Switser to prepare an exciting sensory feast for the audience. Certain passages dazzle. The arrival of the helicopter, for instance, is a gloriously theatrical sequence. And the big finale — a violent, tragicomic production number at a wedding reception — is choreographed mayhem, beautifully executed.

I imagine that finding just the right approach for a play like Big Love could be a particularly tricky balancing act for actors. Landau underscores the self-conscious theatricality of Mee’s world throughout — as in moments when actors slam their bodies hard against the back wall of the stage, onto which is projected a distant seascape complete with undulating waves. It would be too easy, however, to say that actors here should aim always for a cartoonish, over-the-top playing style. Mee may embrace expressionistic slapstick, but he is also a social commentator and a poet. Audiences need to grasp his ideas, and performers need to take his language seriously.

I imagine that finding just the right approach for a play like Big Love could be a particularly tricky balancing act for actors. Landau underscores the self-conscious theatricality of Mee’s world throughout — as in moments when actors slam their bodies hard against the back wall of the stage, onto which is projected a distant seascape complete with undulating waves. It would be too easy, however, to say that actors here should aim always for a cartoonish, over-the-top playing style. Mee may embrace expressionistic slapstick, but he is also a social commentator and a poet. Audiences need to grasp his ideas, and performers need to take his language seriously.

Generally, the actors here have successfully avoided being “too big.” If they’ve erred, it’s on the side of reticence: Portions of the play seem a bit too subdued.

Some especially effective actors include the likable Jones; the agile and earnest Steggert; the scowlingly commanding Sargeant; Ellen Harvey as a life-affirming Italophile named Eleanor; and Preston Sadleir as Giuliano, a torch-singing young Italian with a passion for Barbie and Ken dolls.