The Broadway League, which comprises theaters and producers in New York City, just released its happy stats for 2014. As ever, the organization trumpeted The Street’s overall robustness and how much money came rolling in to Broadway. It was a lot: a record $1.4 billion, with attendance setting a record, too: 13 million theater-loving souls. The latter was an increase of 13 percent over the year before, helped by there being more than 1,600 “playing weeks” in 2014. (Playing weeks are the number of weeks that a theater is hosting a running show rather than sitting empty.)

Reasons for the high numbers range from the League’s explanation that “producers are giving audiences a variety of plays and musicals to please many tastes” to the unfortunate truth that an average Broadway ticket now costs more than $100. The Los Angeles Times notes that Manhattan playgoers are forking over nearly $104 per ducat, which is up 5.5 percent from 2013 and 34 percent since 2010. Producer Stephen Hendel told the LA Times, “At some point, Broadway shows run the risk of pricing tickets beyond the capacity of many potential audiences.”

But are we seeing that already?

Yes, customers will run to attend something they really want to see – Hugh Jackman clean a fish, Bradley Cooper be an elephant – and pay whatever it takes to do so. And the holidays will bring tourists and families out of the woodwork to see the warhorses, so shows like “Phantom” will jump from making $600,000 a week to a million, and shows like “Wicked” will make enough money to support a family of six through three generations of college.

Lost in all the cork popping, however, is one troubling trend: new musicals are having a rough time of it. Not so long ago, straight plays struggled, while musicals seemed worth their production expense because if they clicked, they’d run a couple of years and pay back in spades – especially when national tours and movie rights added to their overall cachet. But the past couple of seasons have seen a reversal, with plays – which are, of course, cheaper than tuners – finding their niche and quickly recouping, while musicals founder.

No question, Broadway is cyclical, and five years could see fortunes change once again, but for the moment, producers have to be asking themselves, “what does it take to have a new hit musical nowadays?” After all, look at some of the recent wreckage:

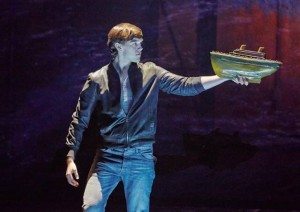

The Last Ship – A new musical with songs by Sting and a book by “Red” Tony winner John Logan and “next to normal” Pulitzer winner Brian Yorkey. Critics liked the score but found the overall mood downbeat, so the show was destined for a tough sell, despite Sting’s name on the credits page. For a month, Sting physically going into the production has hugely boosted ticket sales, but with him leaving the show Jan. 24, advance sales trickled once more, and “The Last Ship” will hit dry dock after only 105 regular performances. As Michael Riedel put it in his New York Post column, “For every `Wicked’ there are at least ten `Last Ships.’”

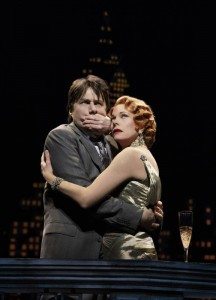

Side Show – Not a new musical, but a revised version of 1990s flop. With no stars and a decidedly non-commercial premise (conjoined twins on the vaudeville circuit), the Henry Krieger and Bill Russell tuner couldn’t translate its terrific reviews into an audience.

Soul Doctor – Well, no one expected this one to break big, but when you figure what percentage of Broadway theatergoers is composed of nostalgic Jews, this tale of charismatic, folk-singing Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach should have at least fostered its core audience. (That the real Carlebach is alleged to have been a child molester probably didn’t factor into the musical’s failure so much as the show’s lack of stars and mediocre reviews.) The tuner is getting another chance off Broadway as we speak.

Holla if Ya Hear Me – Broadway may tolerate ersatz whitebread rap (cf “In the Heights”), but the real thing, in an urban ghetto setting, closes faster than a speeding bullet.

First Date – Fun but nothing special, with charming and near-break-out leads (Zachary Levi and Krysta Rodriguez), this small-scale musical comedy will likely have good prospects for regional productions, but Broadway rejected it. Variety notes that the tuner may have struggled because it opened in late summer (instead of, say, the fall rush).

Rocky – Huge name recognition, huge ring, huge scale – huge losses.

The Bridges of Madison County – So what if Jason Robert Brown won a Tony for his lyrical score and critics loved everything about Kelli O’Hara except her accent? So what if women snuffled in their handkerchief’s when Laura Benanti’s ex-husband kicked the bucket? The show was a dull drag and audiences responded accordingly. However…

Bullets Over Broadway – Seeing this one in previews, I thought, “Hmm..funny book by Woody Allen, zany plot, big-scale production, a star-is-born turn from Nick Cordero and Susan Stroman at the helm. It’s a hit!” Reading the opening-night reviews, I thought, “Uh oh. It’s not.” It wasn’t.

Big Fish – Susan Stroman at the helm, Norbert Leo Butz at the prow, nobody climbing on board.

After Midnight – Every review was a rave, and audiences left this revue jumpin’ and jazzed. Yet this Cotton Club nostalgia trip didn’t come close to recouping its $7 million cost.

All of these examples come from the past two seasons alone. And the rest of 2014-15 doesn’t bode well for “Honeymoon in Vegas”, which, despite an out-of-town rave in the NY Times, has been hemorrhaging money in previews; and will likely see the fast ends of at least half the tuners coming in the spring (will it be: “Something Rotten!,” “The Heart of Robin Hood”, “It Shoulda Been You” or “Doctor Zhivago”? Place your bets now.).

All of these examples come from the past two seasons alone. And the rest of 2014-15 doesn’t bode well for “Honeymoon in Vegas”, which, despite an out-of-town rave in the NY Times, has been hemorrhaging money in previews; and will likely see the fast ends of at least half the tuners coming in the spring (will it be: “Something Rotten!,” “The Heart of Robin Hood”, “It Shoulda Been You” or “Doctor Zhivago”? Place your bets now.).

As the L.A. Times and posters on AllThatChat have pointed out, ticket prices may be most responsible for the chilly reception musicals are receiving on The Street. $200 to see “Wicked”? Sure. $150 to see the Tony-winning “A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder” (which struggled mightily until awards season)? You bet. But $120 to see something interesting with no stars and only-pretty-good reviews when you can stay home and watch “Game of Thrones” on Netflix? Problematic.

And I wouldn’t be surprised if the secondary market is hurting the most. A show that can’t sell out will, of course, offer its unsold ducats to TKTS, TDF and other discount services. When orchestra seats ran less than $100, half-pricers cost about as much as a nice dinner with a drink or two. Now that regular, plain-old orchestra seats cost $140 and up, you’re talking about $70 for a two-fer PLUS fees, handling charges, and all the other add-ons (parking, transportation, baby-sitters, M&Ms brought to your chair). Even beloved TDF is not immune, with Broadway tickets pushing towards the $40 mark (not counting the organization’s annual fee). Sure, $40 for a Broadway show is a steal these days – but perhaps not for subscribers who remember paying only $20 not so long ago.

Anyone can point to individual shows that are exceptions to the rule or explain why each and every Broadway production is different, so making general claims about an overall problem is tricky. And, as has oft been said, the only thing anyone knows about Broadway is that nobody knows anything. Still, when giant (“Spider-Man”), middle (“Madison County”) and small (“First Date”) all fall, investors have to be wondering if the only way to keep a musical afloat is to hang onto the coattails of a big star (Emma Stone, Alan Cumming, Adele Dazeem) and pray we don’t suffer another economic recession. And maybe figure out how to produce a lavish musical with a weekly nut of $29.95.*

*Not counting theater-restoration fees, natch.