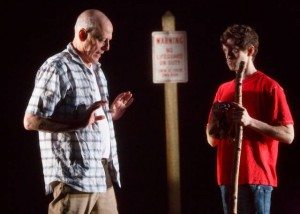

Playwright Dan LeFranc’s Rancho Viejo explores life’s big questions through the residents of a small town in Southern California. With direction by David Aukin, the production at Playwrights Horizons is a three-act, joyously absurd search for the meanings of existence. Whether any is found is for the audience to decide. Below, Mr. LeFranc discusses world building, the American mythology, and and why ambitious art is more important than ever.

Where do the characters of Rancho Viejo come from?

The play spun out of one of the first plays I wrote, Bruise Easy. I’d seen Daniel [Aukin]’s production of Melissa James Gibson’s play This at Playwrights Horizons. I was a huge fan of Daniel’s. He became interested in Bruise Easy. He was like, “I’m not sure this play totally works, but I’m interested to find out what we can do with this thing, and see if you’re interested in possibly developing it.” I was like, absolutely, because I think Daniel’s one of the greatest living directors. So we got some actors together and read Bruise Easy at New Dramatists. It’s a two-hander with twenty somethings and a chorus of neighborhood children. Daniel was like, “I don’t know that that chorus is really gonna play onstage, maybe there’s another approach to having a jarring, unexpected risk in the play.” I thought it worked fine. But I was like, “Alright, I’ll give something else a try,” so on a lark I cut all the kids from the play. What would be really disruptive and weird to have happen in the middle of this play? I decided maybe five scenes in, we’ll suddenly be inside a living room, there will be four characters in their 50s, 60s, 70s, hanging out and talking. We’re in a different place suddenly. So we read that stuff with our actors. Daniel turned to me afterwards and was like, “That stuff is awesome, but I think it’s a different play,” and I agreed. Then I just started writing scenes. I wrote probably 1,200 pages of this thing before I started to craft it. Even out of those pages there are a few scenes and ideas that remain in the play that you saw. A lot of it was world-building. I created a lot of characters, the ones that owned the play are the ones that stuck.

You’ve said that your early undergrad work took place in these Beckett-like voids.

Like all artists, you learn by imitation. Before you can figure out your voice and what you do, you’re just sort of groping around, trying to figure out, how do I fit in? I deeply admire Beckett, Thornton Wilder, Suzan-Lori Parks. Daniel Aukin left around a copy of The New York Review of Books, and in it was a review of the fourth volume of Beckett’s letters. I was reading while watching the play backstage. I was thinking that there’s a lot of Beckett in this play. I have little in common with Beckett. Part of his aesthetic is somewhere in what I do. To say I’m doing Beckett, Chekhov, Molière, feels totally false. But as a young artist, you’re like, maybe I am Beckett, James Joyce, Suzan-Lori Parks, and you take on their modes, try them on for size. Then you kind of figure out, maybe I can wear Beckett’s pants but I can’t wear his hat. (laughs) Out of that comes your own thing, for me at least. I still feel like I’m searching for it. Different plays bring out different parts of one’s personality....It doesn’t surprise me that I wrote this play but maybe it surprises other people.

How do you collaborate with a cast?

They’re inside of it...I have to listen to them. In Rancho Viejo I have a group of actors who are able to clearly explain what they’re feeling doesn’t work and I’ve been able to address those things. Sometimes it’s watching someone struggle with a moment, they’re not telling you it’s wrong but they’re helping point at the problem spot. There are some writers who I think are much more stubborn about their scripts. They’re like, “this is the text, and this is what we’re doing.” I am the opposite of that. Rancho Viejo changed drastically, we reworked tons of scenes. We have this really arcane idea of the sole author who’s masterminding the whole thing. I’m in charge of the text, but my job is also to listen to other people’s ideas and incorporate what I think fits in this world.

In 2007 you said that in your dream world “all the proscenium arches and black boxes would be torn up and replaced with environmental spaces,” that the truest theatrical experience, in your opinion, “is one where the actor/audience relationship is more porous.” Has your aesthetic changed?

That’s a very idealistic statement that I still feel somewhere inside of me. That’s a grad school-y thing to say. Since then I’ve moved to New York and been a working playwright and TV writer, had to contend with the realities of what the spaces are, what the funding is, what audiences expect...I would say I’ve adapted my aesthetic. Rancho Viejo is like, if we have to have a proscenium, let’s push it to its limits. The play questions what we put in a proscenium. What kinds of stories are we telling? Why are telling them? What makes them relevant? The characters are like, “We’re not important, why are we in this play? Why art at all?” The play is in a way a response to theater, and what stories we decide to tell face to face. I think occasionally we have something amazing in the American Theater but very often it’s pretty anodyne. You don’t need to tear down the proscenium to bring actors and audience closer to each other, you can still do that within the structures we already have built. It is my mission. Otherwise, why am I doing this? It’s not to make money. You’re only gonna reach so many people. All I have control over is my own work, I try to be as ambitious as I can be in every project. There are a lot of forces working against ambitious art in the United States, and I think those forces are also about to get a lot stronger, which means it’s even more important to push the boundaries beyond what the system is comfortable accepting.

You once said “works of powerful, imaginative, and visceral force are often dismissed in favor of the comfortable and familiar.” It’s 2016. How can theater lead those uncomfortable conversations and chart unfamiliar territory?

We can’t allow the status quo to be the status quo. I think artists need to lead the way, and so do producing entities, critics, and audiences. We’re at a crossroads...who’s going to define the American mythology moving forward? I think it’s more important than ever that artists are clear-eyed and ambitious, willing to take the necessary risks to tell the truth, however difficult and uncomfortable that might be. It may not be rewarded by audiences, producing entities, critics, that doesn’t mean it’s not valuable. I hope we don’t fall back on safe choices in our art.

"Rancho Viejo," now in previews, opens December 6 at Playwrights Horizons.