Whether writer Mac Rogers and director Jordana Williams are writing about aliens, robots or Frankenstein, there is always an extreme effort to create a sense of realism and relatability despite involving circumstances most people will never experience in their lives. Their new play Asymmetric, now performing at 59E59, is no exception.

The show is a spy thriller taking place in the CIA where Josh, a burned-out agent is brought in to ferret out a mole in his former operation. The only problem is, the mole is his ex-wife and ex-partner, Sunny. Along with agents Zach and Ford, they dig up painful pasts and morally ambiguous futures. I spoke to Mac and Jordana via phone.

Asymmetric is a spy thriller, but it's also a love story -- do you think one is more emphasized than the other?

Mac Rogers: The initial way that this play was written was for a serial installment format for Saturday Night Saloon, at the Vampire Cowboy theater company and the requirement was that you had to mash two genres together. I happened to be in the middle of trying to outline a play that just wasn't working out at all -- it was about a marriage falling apart and it wasn't making for a very good play, so when this opportunity came along, I was like, 'What if I took the few salvageable bits from the play I'm outlining but make both characters spies? That sounds a lot more fun to me.' So because of that specific requirement that it be a genre mash-up I tried to keep the elements equally balanced. I wanted both those things to be clear and not favor one over the other, but if it ever came down to it, I'd try to favor the love story because ultimately that is what the audience carries away with them.

Jordana Williams: The big emotional things that happen in our lives also happen while we're living our lives and managing our careers and being all the different things that we are. These guys were colleagues and they were married and lately they haven't been either so they have to figure out how to do both again, but on some level both of those kind of patterns and attractions are there. Life tends to be a jumble of all our different parts all together and it's fun to sort them out and see where one takes precedence over the other.

So a lot of the plays you've collaborated on together have had some element of absurdism (Frankenstein Upstairs, Viral, Hail Satan); what made you decide to work on a more serious, all-too-real story about the CIA?

JW: Well what we try to do is take a genre that's extreme in some way and make it feel real. We try to take these truly extreme circumstances but treat them as if they're being lived by real people. Even if they aren't the kind of things you would ever expect to encounter in your actual life, we try to make sure that the way the character respond to them feels truthful and feels relatable, we try to find a way for the audience to be like 'Yeah I guess if the world were colonized by 9-foot bug-like aliens, I might feel like this and that.'

MR: Certainly every spy story to one extent or the other is going to be kind of a metaphorical study of how highly qualified workaholics relate to one another. They work long hours, they're highly versed in a lexicon that not many people are familiar with, they have a certain amount of difficulty balancing their professional and personal life. That's the lives of many adults in first-world economies that don't work in quite intriguing fields, but that deal with a lot of the same concerns. I think a lot of people see a key element of themselves in spy stories, which is part of the fun of writing them and watching them.

A lot of the scenes revolve around the serious and controversial issues of today such as drones. There is also a lot of talk of patriotism in the play, especially with the character Ford, who saw these morally ambiguous problems as very black and white. Was there a political message you wanted to send with this play?

JW: One of the hallmarks of a Mac Rogers play is that he's not going to put a character out there who doesn't have a morally consistent view of the universe so you won't necessarily know what Mac thinks, but every character who comes out on that stage has a passionate position that is based on something that makes internal sense. I think it's a confusing thing to figure out how to be a patriot or even if it's right to be a patriot and I think I would so much rather grapple with the idea that people who are different from me might actually have a point about some things than make fun of a viewpoint that's different than mine. We're not trying to preach anything, but I think each of these four characters has a position that they believe in and that they are willing to fight for.

MR: One thing that a lot of people had to grapple with was that there's not a tremendous amount of daylight between Democrats and Republicans on foreign policy issues. You can't say that the current administration doesn't use drones as much as the Bush administration because today they use them much more. When rewriting the play we needed to set it in a much more ambiguous universe, a much less morally clear-cut universe, which in turn then affected the characters, but I made a conscious decision to say that Ford isn't going to change much, because Ford doesn't change from era to era. He is absolutely sure he's right, he's sure he's doing the right thing and it doesn't matter how the world is changing around him, he's a constant. I'm just going to strengthen who Ford is and not show more shades to him because I think Ford is a guy who shaves down any subtleties that he has.

Besides political influences, were there any books or movies that impacted the play?

MR: Well in the original story, I very consciously decided to very much focus on the John le Carré tradition - very specifically Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. I was fascinated at the idea of the washed-up spy who's been pushed out of the intelligence community being brought back in to track down a mole who is working in the intelligence agency that he helped to build and raise to a certain level of success. What interested me about Tinker Tailor Solider Spy was that in a lot of le Carré's early works, he really didn't have women as a major presence, women wouldn't really turn up much in the actual events of the story but rather loom large in the shadows. George Smiley's wife is a more of an off-screen figure who haunts a lot of his private thoughts and a lot of his relationships with his fellow spies. I thought that it would be a lot more interesting if George's Smiley's wife was also a spy and a major player in the story and then I was like, even better, what if the wife was the mole - that's a really interesting story and it pushes the conflict front and center. I'm sure in terms of the writing there's tons of traces of stuff from any number of spy thrillers, Mission Impossible, Alias. Especially when you're writing officials talking in jargon there's no escaping the influence of Aaron Sorkin.

JW: The characters on The West Wing in particular - the way their professional lives and their personal lives are all sort of muddied up. People who work that many hours a day and whose personalities and lives are so defined by their jobs, their coworkers become their closest people, and so that mixture has influenced how I approached directing some of the scenes.

Why is this story important to tell to audiences today and what audience are you trying to reach?

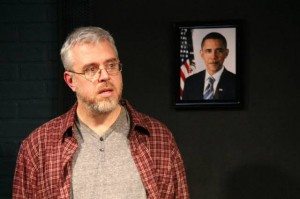

MR: There's a huge non-stop argument among progressives and liberals that's been going on for years about Obama. How do we feel about what we've achieved with a certain amount of progressive power? Obama happens to be the symbol for that, and we use his face in the play as a symbol for that, but the question is when a somewhat more progressive force comes to power, what can it achieve, what can it not achieve, what are the compromises? I think it's a long simmering conversation between liberals. It's not even good enough to be liberal now, you have to be a radical - you see a lot of change by structures being torn down with wide-spread protest, you see that with the Occupy Wall Street movement, you see it in Ferguson. There's a real debate over whether liberalism and progressivism is good enough, and that to me is a big part of the play that I wanted to tackle from a bunch of different points of view - that to me is the current relevance.

JW: For me it's about, having been really excited a few years ago and then having gotten really fatigued with politics. I used to read an enormous number of political blogs and I just don't have the stomach for it anymore, and I find that I was to engage less and less -- and that feels like not the right answer, but I don't know what the right answer is. I just hope it gets people talking and thinking about their level of engagement and whether they feel like that's the best they can be doing right now.

Is there anything we can expect to see in the future from you guys together?

MR: There are a lot of possibilities. There's a couple of projects. We're looking at opportunities to remount a few of our better received, especially the Honeycomb Trilogy. We're at different stage of now exploring different ways of bringing those back but in December there's a play I've spoken to Jordana about, it'll be a major collaborative approach. So there's definitely some irons in the fire but nothing we've pulled the trigger on yet.

Performances of Asymmetric continue at 59E59 through December 6. For more information and tickets visit https://www.59e59.org/