When stories and histories get passed down, what details get left behind? How we tell stories — and what gets left out — sits at the heart of the ephemera trilogy, a visual piece written and performed by Kimi Maeda that forces us to think about what we carry with us and what we don’t.

Drawing upon Maeda’s Japanese-American identity and family history, this trilogy of short pieces is tied together by themes of memory, forgetting, how we tell stories and what it means when your home leaves you behind. The first two pieces, The Homecoming and The Crane Wife, take on these themes in a fantastical way, as Maeda weaves her personal history with Japanese folklore and otherworldly tales. The third piece, Bent, takes a far more documentarian approach, as Maeda shares the history of her art historian father, who spent part of his childhood in a World War II internment camp and now struggles with dementia, and Isamu Noguchi, the artist he most admired.

The ephemera trilogy is marked by a straightforward narrative style, as voiceover narration and interview clips of Maeda’s parents tell the story simply with little dramatic fanfare. That the tales are so compelling with so few dramatic flourishes is a testament to the power these stories hold, though the piece sometimes gets muddled by the massive themes it’s trying to convey.

What truly drives the piece, however, are Maeda’s artistic visuals, which transform her straightforward stories into masterful works of art. In the first act, Maeda brings her fantastical world to life by using shadow puppetry in a stunningly innovative way. A scroll of images stretches across the stage, and Maeda tells a story by selectively shining a light and camera onto one small part of the larger image, projecting it onto the back wall. Choreography and cinematography are intertwined as Maeda’s small movements spin this single wall of static images into an entire cinematic world.

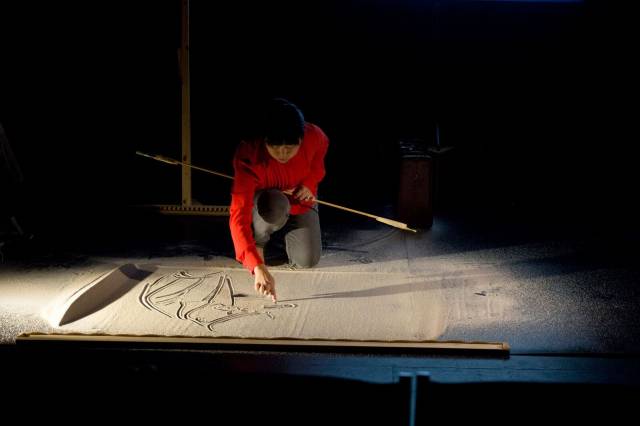

For the second act, Maeda tells her father’s story with the help of sand art, which is filmed from above and projected. Maeda’s live art making is as compelling as the story she’s telling, as the visual process evokes a Japanese zen garden not only in its form, but in the mesmerizing calm these live drawings produce. As the intricate images are brushed away moments after their creation, their transience, too, reminds us all too clearly of how quickly details are swept into the realm of memory.

By relying not only on sand art but on the fleeting form of theatre itself, the ephemera trilogy asserts its purpose in its actions as much as its words. Maeda presents surviving 1940s footage that reminds us of the dominant — white — narrative of Japanese-Americans during World War II, while presenting a more personal, vital perspective of the same history that will soon fade away. Through the ephemera trilogy, Maeda’s tales become clear, but so too do the enormity of the details and stories that get left behind. We’re all the more lucky, then, that this is one story that gets to be told.