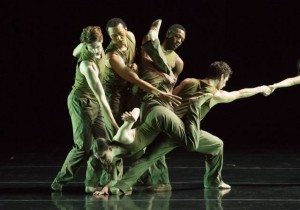

Jessica Lang Dance returns to the Joyce Theater June 14-19 with the New York premiere of her latest work: Thousand Yard Stare, set to Beethoven's late string quartets and created in honor of wounded veterans and those affected by war. The program also includes Sweet Silent Thought, inspired by Shakespeare’s sonnets to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the poet’s death and featuring original music by Jakub Ciupinski, as well as company classics such as Solo Bach (2008), Among the Stars (2010) and i.n.k (2011). A highly sought after choreographer with commissioned works worldwide, Jessica Lang is known for her visceral aesthetic and highly crafted choreographic work. Often influenced by visual art, her choreography utilizes strikingly powerful imagery that evokes emotional response and leaves lasting impressions.

Dedicated to dance education and giving back to the community, Jessica Lang is proud to announce the opening of the company’s new home in Long Island City, scheduled to open in September of 2016. In addition to housing the company, The Jessica Lang Dance Center will offer a little something for everyone in the community: youth programing, adult classes, as well as affordable and handicap accessible space rentals. As a proud Astoria resident, I was happy to be one of the first to welcome Jessica Lang and her company to Queens. We spoke about the artistic vision shared between Jessica and her husband, Kanji Segawa--JLDC Director and current member of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater--as well as what it means to become a staple in the artistic community of Queens.

When did you begin working on Thousand Yard Stare?

In May of 2015. [That] is when I did the research and then we created here at [Baryshnikov Arts Center] in three weeks. It was fast and intense. It was such an emotional experience—really raw. I wanted it to be an honest approach and respectful; and what I learned, I wish I could unlearn, but at the same time I would be living in some sort of bubble and that’s not good either. So it was a very enlightening experience—eye-opening for everyone [involved].

So it was a pretty quick process. How much of the process was research?

It was an entire month. (Sighs) You know, it doesn’t take that much to inspire. You can have just a little bit of information and make a 20-minute dance out of that. But it got to a point where I was truly affected to the point of constant crying. My parents were the one’s who said: "Pull back. Stop with the research. I think you have enough. You’re an artist. Just take what you know and sit on it for a minute. Then go into the studio, pick up your brush, and paint. You don’t need any more information."

One [veteran’s] story alone is enough to make many ballets. But I took in as much as I could. And then when it was too much emotionally, I stopped.

What out of all of these powerful stories had the most significant impact on you?

Speaking to one particular veteran… it felt a little unfair how he ended up in the service. It felt a little bit like he was unprotected by our government, and that frightened me. He was also standing up for his belief, but it wasn’t from a place [where] he necessarily wanted to. It was a choice: he either had to do this or do something else, and the “else” is not something he wanted to do. It was a trade, and he was put in the front; he was put in harm’s way. It’s hard to hear someone’s stories, especially when you’re an imaginative person—I don’t know what he’s seeing in his memory, but I’m seeing something he’s describing. What he was describing was just very, very raw. That person really made an impact on me.

Can you tell us a bit about the veterans' drawings that were incorporated into the costume design?

Many people were quiet and didn’t want to share. Respectfully, I would just say thank you and here’s [another] opportunity; if you don’t respond, it’s okay. For those who did [respond], I would send them my music and just ask them to draw whatever images came to mind: [It doesn’t have] to be from war, just listen to the music and sketch, it’s not a masterpiece. I let [costume designer Bradon McDonald] choose the images from a costume point of view, and he transferred those drawings into textile, and then we made it almost a camouflage. There’s one that’s really beautiful to me that has a heart, and it has an arrow and an arrow back, [to] a heart [that’s] less full. Then a heart that’s empty, and an arrow and an arrow back [to] a broken heart. And I know this veteran made several trips, and it affected his personal life when he was home. It’s carrying their stories more symbolically on stage.

Where did the title of the piece come from?

One of the gentlemen I spoke with, who is actually in the dance field [and a] technical person, was raised in an area of war; he was a civilian. He saw war and [saw] the American Army helping his country. I played the music for him and he said: "the first thing I think of is the thousand-yard stare, that image from [Life] Magazine." And I knew it as soon as I heard it—that’s our title. I don’t necessarily want everyone to go looking at the image because it is really frightening. It’s that person who’s lost in a memory or lost in shock; I think of it as a stare into the past.

What do you hope the viewers take away from the piece considering war as both timeless and timely?

I don’t like to define my work and I don’t like to say what you should take away, because I don’t know who’s watching and their experiences—if they are connected to the military—I don't know. But I hope it brings forward more consciousness and support toward veteran causes. And to understand that for some people it’s a choice and for some people it’s not a choice to go. Even though there’s not a draft, sometimes this is the only option. It depends on who you talk to. Some people really want to fight and some don’t.

My board member who approached me with the commission of this, he is a former Marine, and he wanted me to take this theme and try my hand at it. I was really hesitant because it’s a huge topic and can be seen as a political statement or a statement in any way. But I just stepped back and looked at it as a human being and [asking] what war can do to a human being—to all of us. I think [the piece] resonates deeply with everyone because you can’t help but see and imagine.

Let’s talk about Shakespeare’s sonnets. There’s a lot of them, and you’ve chosen to construct a work based on five of them: #30, #40, #64, #71 and #105. These are from a larger chunk of sonnets that communicate themes of time, love, and a sense of fading away. Why did you choose these five?

I listened to every single one. That was a really long period of research—it was exhausting (laughs). I did have people who it’s their job to analyze Shakespeare in general, but the sonnets specifically. So, I could see the meaning translated and their opinion as a scholar, [e.g.] this one didn’t actually follow a sonnet structure; this one is a gem; this is way too overused. There’s a couple that are used a lot in wedding ceremonies, and if the couple really knew what it meant… (laughs).

I created two pieces this year on this theme. One for Birmingham Royal Ballet called Wink that just premiered. It’s with the same composer, but it’s structurally very different. I always say that Van Gogh didn’t paint one sunflower and say, "nailed it!" It’s a little bit more of the visual art approach that you take a theme and try and paint different pieces with it. [Sweet Silent Thought] is smaller, more intimate, and a quartet. These five [sonnets] came to me because of the theme or their meaning, the beauty in which they are read by the actor I was listening to—the flow of the rhythm and the tone. It sounds musical to me.

And I know text can be frustrating because [we] try to listen to it for meaning [while] at the same time visually watching dance. If you know the sonnets, great. You’ll know that I’ve stayed very true to the meaning. But if you don’t, you’ll get it if you just watch.

What challenges did you run into working with such renowned literary work?

I was approached by [David Bintley], the director of the Birmingham Royal Ballet, a gentleman who is English and has a huge history in the UK. He was putting together a season this year for his company that was all focused on Shakespeare. They are doing The Moor's Pavane, Ashton, MacMillan, all of these famous ballets that are associated with Shakespeare. And he said: "I would love to commission you to do a new work—I’m not telling you it needs to be on the sonnets, but I’m telling you that the sonnets haven’t been explored in our repertoire. Would you like to take that on?" I immediately said “Sure!” and then immediately got nervous thinking, Oh my god…they hired an American?! (laughs) I was scared and so I put a lot of thought behind it.

One thing I was sensitive to, is that there is [existing] music for the sonnets, but mostly they are sung. And I didn’t want to hear the sonnets sung; that’s not how they were intended in my opinion. [Felix] Mendelssohn wrote the music for [Frederick Ashton's] The Dream inspired by a Midsummer Night’s Dream. There was nothing like that in history—a piece of music inspired by all sonnets. So I approached David about commissioning a contemporary composer who would feel the importance of maintaining history and making it relevant today—if it hasn’t been done, let’s do it so at least everything is interwoven cohesively.

These two pieces are both somewhat heavy (although I hesitate to use that word). It seems that these pieces will be counterbalanced nicely by the other three in the program, which I would describe as more fun and joyous. Can you tell us a bit about what to expect from the show as a whole?

Solo Bach is a really nice way to welcome the audience. It’s short; it’s sweet; it’s fast; it’s entertaining; it’s hyper-musical; and then it’s over. Then [we] move on to the more balletic story en pointe. We go somewhere more quiet…or romantic if you want to say that. [Among the Stars] is actually one of our more popular pieces on tour. It’s simple, and I think it’s the simplicity that people appreciate. Then we go into Thousand Yard Stare—this heavy, emotional experience—and then take a breath at intermission. We come back with Shakespeare, which is different in its heaviness. The movement is really contemporary and the music is driving. The second half [of the program] is all Jakub Ciupinski. You’ll see something we made this year and something we made at the beginning of the company, [closing with] i.n.k., which gives a nice point of reference of our own time and our own evolution.

I’m very excited about your new home in Long Island City, and I know you are too. Can you tell me a little bit about the Jessica Lang Dance Center?

It’s really exciting. We are hard at work to open in September. We are [building] a dance center that is very much for everyone. First and foremost, it will be the home of our company. So we will be there creating work, rehearsing—it’ll be something the community can come and observe and enjoy. We will just weave ourselves right into the fabric that is already so artistic in Queens and in Long Island City. We want to open our art form to everyone, so we have a youth program that is designed for imagination and creativity through dance, visual art and live music. Every class has live music, with the exception of Hip Hop and Dance Broadway. We are only right now going to [age] 12, because in our area that’s the highest of the kids that live there. We have to start somewhere, and we have plans to grow with the community and see where the demand is. Then we will get into a teen program. My husband, Kanji Segawa, is the Director of the center. He is doing all of the programming and building the faculty. He is a dancer with Alvin Ailey… and he’s not leaving. He’s still doing that.

Does he get that question a lot?

Yes! (laughs) He’s not leaving the company.

We’ve been working together for 17 years and we have such a shared vision. This is an opportunity for both of us to grow as individuals and how we can contribute to the world, the society, but also to our society in the dance field—how we can provide space for other artists looking for it. I’m here to say that there’s not enough quality dance space in New York, so I’m happy to build something that will offer more companies like ours (who need to rent space and are running from studio to studio) quality space so that they can also rehearse. Mark Morris—he’s a mentor to me and someone I admire so much of what he has built. I observe that and that’s the model I want to embody—that single vision choreographer who gives back to the community. What he has done for the Brooklyn community is remarkable and we [are making] every effort to bring that same sense to Queens.

Jessica Lang Dance performs June 14-19 at the Joyce.