American theatre still has a long way to go when it comes to the preservation and dissemination of stage productions. While the Performing Arts Library at Lincoln Center has been archiving productions for decades, the tapes are meant to be merely for historical purposes and have no artistic value of their own (not to mention, they can only be watched once by researchers, so planning must be done carefully). Across the pond companies like the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company have mastered the art of creating hybrids of sorts using multiple cameras and a setup that marries the elements of stage productions with cinematic capture, i.e. audiences who attend screenings or watch on television can see close-ups and alternate angles that they wouldn’t get sitting in the theater.

Even though the Brits have become more efficient when it comes to getting theatre to as many audience members as possible, in as many mediums as they can, Americans seem reluctant to take up the practice, until recently there were very few Broadway shows that were available to see outside the theater. In recent years the success of She Loves Me captured by BroadwayHD, and Newsies, which saw original cast members put on an encore performance years after the show ended (it’s also now available on Netflix) has made the digital future of theatre seem brighter.

It’s strange to think that four decades ago, visionary producer Ely Landau was already trying to make the great theatre classics available for people outside New York (and perhaps even New Yorkers who couldn’t afford to go to the theater), rather than coming up with plays on film, he decided to create a subscription based service (similar to the ones theatre companies still have) which would offer audiences an opportunity to watch a feature length version of a classic play, starring some of the world’s biggest stars. For two seasons, from 1973-1975, Landau was able to gather up to half a million subscribers who would attend a screening in which ushers dressed up, and they were provided with luxuriously bound programs titled Cinebills.

In total, Landau’s landmark American Film Theatre series was comprised of fourteen films, one of which never was screened, but made it to the DVD set that came out in the mid-aughts. For decades, the films in the series have gone largely ignored when it comes to retrospectives and festivals, but the revamped Quad Cinema is about to change that with their incredible Screen Play: The American Film Theatre program, which will see 11 films in the American Film Theatre series back on the big screen for the first time in years.

Before taking on the American Film Theatre project, Landau had already successfully developed the Peabody Award winning Play of the Week series, which aired on WNTA-TV and offered audience members the opportunity to see stars like Lois Smith in The Master Builder, or Lillian Gish in a Truman Capote play. Landau’s ambitions were never thwarted by the limited budget, and stage and film stars willingly worked for much lower salaries than they were used to, in order to be in the Landau productions.

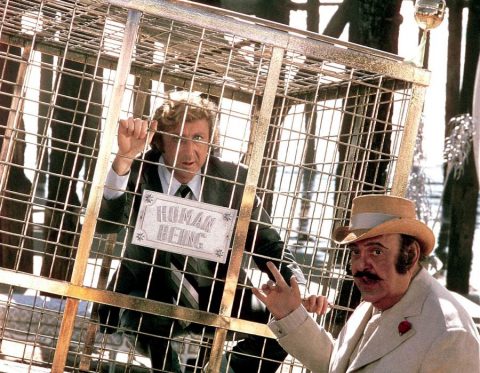

There’s the legendary Katharine Hepburn playing the matriarch in Edward Albee’s A Delicate Balance, a Tony Richardson film which also included Paul Scofield and Lee Remick in the cast. For Eugene Ionesco’s Rhinoceros, director Tom O’Horgan reunited Zero Mostel and Gene Wilder after the success of The Producers to have them play best friends who are baffled by the realization that people in their town are turning into the title animals. For The Maids, Landau paired director Christopher Miles with actors Susannah York and Glenda Jackson who play the title servants in Genet’s play about power and seduction.

Even when there’s an element of efficient, rather than artful, workmanship in most of the films in the series, most of them have elements that more than stand up for themselves in terms of justifying their cinematic existence. The productions aren’t bare bones, but they’re not extremely luxurious either, they respect the text, even if sometimes they veer slightly from them to compress plot points. Landau was able to commission films that achieve the task of preserving what makes the plays so wonderful and important (even works that seem to be “lesser” with the advantage of time) while allowing established and up and coming directors to showcase their talents. In a nutshell, they were win-win projects.

Another element of note is the inclusion of Butley and In Celebration, among the films in the series, given they both offer sensitive portrayals of queer characters, at a time when representation of non-heterosexual characters was still mostly sensational. Butley, which was directed by Harold Pinter and certainly highlights his idea of male anxiety, is anchored by a mesmerizing performance by Alan Bates who plays a professor who loses everything in one day. Landau’s talents as a producer should also be commended for his keen eye for choosing who directed what, the fact he has Lindsay Anderson direct David Storey’s In Celebration, was the perfect marriage of two socially conscious sensibilities that might’ve otherwise never occurred.

But perhaps the towering achievement in the series was John Frankenheimer’s monumental take on The Iceman Cometh starring Robert Ryan, Fredric March and Lee Marvin as the iconic Theodore “Hickey” Hickman. Frankenheimer’s larger than life interpretation of Eugene O’Neill’s play highlights everything that was great about cinema during the 1970s; it was a time when new artists were both in awe and ready to break away from the first masters of the form. With Hollywood legends March and Ryan turning in their very last screen performances, and Marvin establishing a new intensity that would define masculinity for the last quarter of the twentieth century, it seems that Frankenheimer’s Iceman was able to do the unimaginable and recreate the lightning in a bottle sensation that live theatre provides. It’s an epic film that we know will never change, but it’s so alive that we feel we can reach out and touch the characters.

For more information on Screen Play: The American Film Theatre click here.