It’s tempting to want to distance yourself from the main character of Max Posner’s new play, The Treasurer. Referred to only as the Son, he’s a hardworking geologist, a loving husband, and a supportive father who has assembled the trappings of a normal, happy life. But, he assures the audience in his opening monologue, he’s going to hell. Why? Because he doesn’t love his mother, Ida Armstrong, a recent widow whose lifelong tendency to spend beyond her means he’s suddenly found himself in charge of reigning in.

As the darkly comic, exacting work unfolds, showcasing David Cromer’s slick directing talents and Posner’s preternatural penchant for blending the absurd with the hyperreal, it becomes harder not to feel for both Son and mother and recognize the undeniable ways that time, distance, and complex, ancient traumas — Ida left the Son, then 13, and his father for a more exciting, lavish life with a journalist turned politician — affect our ability to communicate, connect and give love.

If it seems precocious that a twenty-something writer should tackle the pathological angst of the twilight years, consider also that the play is, in large part, autobiographical — about his father’s relationship with his grandmother. I had the opportunity to dig into the work with Posner, an undeniably rising star of the New York City theatre scene who has drawn comparisons to Chekov and Williams and is still disarmingly excited that his plays are being produced at all.

You write that you spent many years on the play, and it’s clear that there’s an autobiographical component. Can you take me back to the beginning? What made you decide to tackle this topic?

I guess I always had this sense that my grandmother was a theatrical character. I loved how she used language. She called everything delicious, whether or not it was edible. So just from the time I was a child I was always very drawn to the size of her performance in her life. I was in a playwriting program at Juilliard and I was trying to write a different play — I don't even really know what play — and then one day I found myself stuck, and I just kind of ended up writing the opening to this play, which is my father speaking. Or an attempt to give voice to some of his inner thoughts. And I knew that there was this chasm between these two people and I was really interested in trying to put that chasm onstage in a way that felt detailed and accurate.

I think that, for me, it's exciting because, while there is certainly a large disagreement about reality between these two people, about what is real and what is not real, I also feel like the primary conflict is kind of within each character. I'm always excited by plays where the ultimate war is not actually going to be completed between two people and really actually is staged internally. So the play at a certain point just seemed unavoidable to me.

When were you able to step back and say: "OK, this play is finished. I'm ready to show this to a wider audience."

I hope I feel that way tomorrow (laughs). I think that I did keep this play really private for a long time, and so the main relationship was really just between me and it. And I felt like I knew that if I was thinking about anyone really watching it, or seeing it, or hearing it that I wouldn't be able to finish it because it felt like the play's energy was derived from this kind of privacy. I love when I go to a play and it feels like a private event. It feels like we go somewhere that we mostly go to alone, we just happen to do it with 128 people. I wasn't sure that I would ever do it because especially at the time when I started this play, and still, in my head, it's hard to imagine plays being produced after I write them (laughs). That's new.

I got to do a workshop of this play for three weeks with the Sundance Institute Theatre Program, and that's when David Cromer came on board. And actually three of the actors in this production were there, and it was strangely in Morocco — they take artists to beautiful exotic locations to work on plays — so we were there for three weeks and I had a full draft of the play, but it was longer and it wasn't quite finished. During those three weeks, working on the play with Peter [Friedman, who plays the Son] and Deanna [Dunagan, who plays Ida Armstrong] and Marinda [Anderson, who plays Allen and others] and David actually turned the play into what it is now, and so that was the moment where I feel like it went from a hypothetical thing that was probably never happening to this other thing. It was helpful that we were working on the other side of the globe so, just in terms of the privacy of it, it just felt very bizarre. We weren't in the same time zone as anyone we knew.

So how does it feel now the play isn't private anymore — to know that hundreds of people are watching it every week?

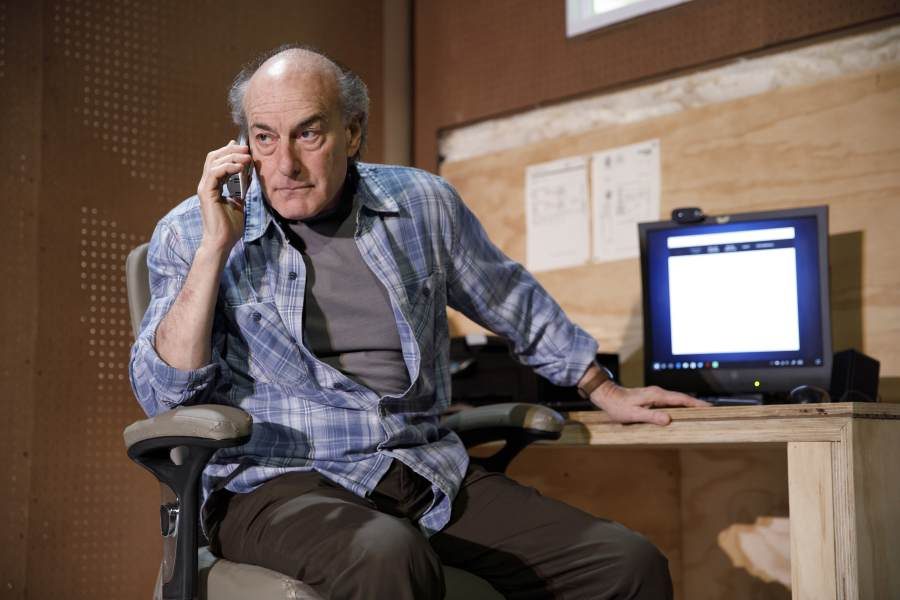

Well, I guess it's complicated. There are moments where I feel like I've broken some boundary because the people in the play exist in some way. Even though, of course, as my therapist keeps reminding me, it's a play, you know? It's not life. It is a thing on stage. But I do think the effort of the play is to try to get at something that's kind of invisible but real. I like to sit in the very very back, and I'm slowly pulling away from watching it. Last night I actually watched it, but on the monitor, on the third floor. I was all alone on the third floor in the Playwrights Horizons office. [Artistic Director] Tim Sanford let me into his office and I just sort of listened to the play and I watched this fuzzy, pixelated version on the monitor, and that felt about right.

When I feel like a monster, like I've exploited the private, family secrets for the benefit of... I don't know, an audience or something, the thing that makes me happy is that it does seem like after the play I end up hearing about a lot of people's mothers and grandmothers, and so I do think that there's a lot of shame involved in the problem of this play. I think that, in its own tiny way, I hope that it gives people permission to talk about it and to hopefully absolve themselves of some of that.

In the beginning of the play, the father character says that he's supportive of his son, or at least sort of indifferent about the fact that his son has chosen to write such an intimate play about his life. Is that true?

It is. It's very true.

What role did you play as the production started to make its way to Playwrights and find itself in the space?

I really admire David Cromer and his mind, so I was incredibly involved with the process just in sort of how the scenes work and how I feel like the play moves, but I wasn't terribly hands on — I really let David figure out how he felt like the play should live after I felt like we had a very shared understanding of what it wanted to feel like. I think that David's production emphasizes the distance between these people, in the way in which a large portion of the play happens on the telephone.

There's a way to do the play where you ignore that fact, because the script itself doesn't really say that they should be holding telephones or that they should be doing anything — it doesn't actually say what you're looking at until you're in the restaurant scene, and then suddenly there are pages and pages of excruciating detail about what you're looking at. But I really like that David's production is actually trying to get at the way that these people are miles and miles away from each other and also the intimacies that can be formed over those distances. I do think that it means that, while you are kind of watching these people alone on phones or obscured slightly, when they finally are in the presence of another person I think that you really feel the difference. That's a lot of what the play is about. Particularly for her [Ida Armstrong's] character. I was really interested in her relationships with these strangers and his [the Son's] relationship with the audience and the way that those two things continue to evolve and then hit each other.

Wow, the phones are such a critical aspect of this staging.

I'm excited to have a play that could have been done in a lot of different ways, and I'm really proud of the way that David has done it. I will also say that these actors have really built these parts with me. Peter and Deanna are such incisive and exacting performers that as soon as I working with them on it, it became clear to me how complete their struggle really wanted to be, and their voices started to become the play.

There are the mother and the Son, who are more clear-cut characters, and then there are two actors who play a wide range of roles. Can you talk about your motivation behind that a bit?

I guess I knew that the play was not going to just be two characters and I also knew that it didn't want to just be four characters, but I did really feel like the thing that is stable and in focus is this one relationship or non-relationship between these two people. So I don't think of the two more choral parts as though they're not playing people, 'cause they are, but they're playing people who are more impermanent in this world. It was really important to me that they were cats very specifically as one of the characters that felt crucial, that had a scene that I felt, we really want it to land in its very detailed reality. For Marinda's character that's Ronette who works at Talbots and sells Ida a pair of purple corduroy pants, so I knew that was the actor we were looking for. That scene is when we first really see this woman in the world. Having a connection or trying to have a connection or trying to have a best friendship with a person. We understand her, both the exciting nature of her past and her antique liberalism.

I think it's a bit tragic and important that a lot of the important interactions she has are with people who are on the clock. They have to talk to her, and they're working. It's not that they don't want to, it's just that it's their job. And she doesn't seem to have many other options for having a conversation. It's exciting to me that his [the Son's] experience of her is just the amount of money that's being drained, but our understanding of each of those dollar amounts is complicated because we realize that every single one of those is her only chance to have a conversation. And then same with Pun [Bandhu]'s character. I don't want to give away too much about the play, but I definitely knew that the final character that he plays was going to be in the play.

I was allergic to the idea of a play where people are changing costumes and doing funny voices. It's so not actually what I'm interested in. But as I was writing the play it felt like that was the form of it, and it felt like they are responsible for the entire world, in a way. Those parts are actually incredibly hard because even though they don't have the emotional journey that tracks throughout the entire play, they're sort of responsible for how the walls of the world live and hold up and how it moves and changes in a lot of ways.