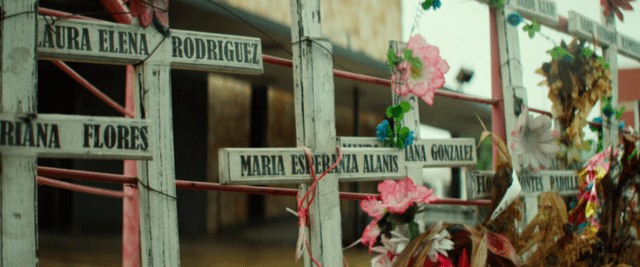

Over 23,000 individuals have gone missing since 2007 as a result of drug-related violence in the Mexico-US border, and while the statistics are impressive in themselves, they’re even more powerful when we see the faces that go along with them. In Kingdom of Shadows, director Bernardo Ruiz has taken on the mission of humanizing the victims by telling the story of three people at the center of the drug war: Sister Consuelo Morales, a nun who devotes herself to helping the victims’ families find justice and solace, Don Henry Ford Jr. a former marijuana smuggler, and Oscar Hagelsieb a senior Homeland Security officer who once worked undercover.

Over 23,000 individuals have gone missing since 2007 as a result of drug-related violence in the Mexico-US border, and while the statistics are impressive in themselves, they’re even more powerful when we see the faces that go along with them. In Kingdom of Shadows, director Bernardo Ruiz has taken on the mission of humanizing the victims by telling the story of three people at the center of the drug war: Sister Consuelo Morales, a nun who devotes herself to helping the victims’ families find justice and solace, Don Henry Ford Jr. a former marijuana smuggler, and Oscar Hagelsieb a senior Homeland Security officer who once worked undercover.

Through their compelling tales we are exposed to a world the likes of which we never imagined, a place beyond the law where human lives are used as currency. Ruiz’s provocative film challenges viewers to ask themselves the tough questions: What is our responsibility in this? Have we done enough? We spoke to the filmmaker

To be honest, sitting through Kingdom of Shadows, was incredibly hard for me. I kept pausing my screener, taking breaks...but I kept watching because it’s a very necessary film. If it was that hard for me as an audience member, I wondered if did you ever go through moments during the shoot or editing process where you felt like you needed to take a breather, go for a walk or something?

I really appreciate this question, and I think what you’re touching on is the importance of telling this story of the narco-world. There are so many projects out there that take this conflict and turn it into entertainment, Netflix has Narcos, there’s that Benicio del Toro film Sicario, of course there are also telenovelas and other projects designed as entertainment, and they tend to be very sensational. Part of what I want an audience to feel in the film is precisely what you’re talking about, the utterly destructive nature of this conflict and how it’s devoured so many lives and harmed people on all sides of this conflict, whether you’re a smuggler, a federal agent or a mother looking for her child. The feeling that you had is important. There were many moments when I had to take a break with my team, but at the same time it’s a privilege to step out of it, there are people in the film, like the mothers, who don’t have the luxury of stepping away.

Those films you mentioned also have in common the fact that they’re told from the perspective of the investigators. We rarely get to hear the victims’ side, and more likely than not, this has to do with how many of them are missing.

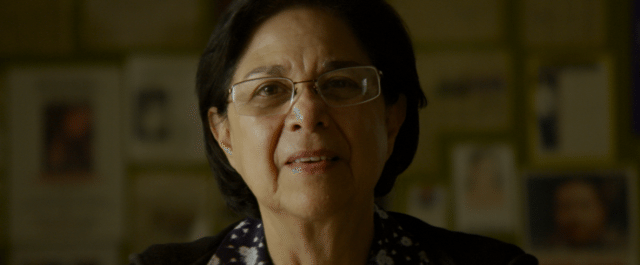

That’s a thoughtful reflection and it was also one of our goals, we wanted to show how complex this is and we wanted to incorporate different perspectives. The film challenges some stereotypes people have about the US/Mexico border and who’s involved in the trade. We have a person who looks like a John Wayne figure who is in fact a former smuggler who worked for the Juarez cartel, a man who looks like a gang member, or a cholo to many people is in fact a high ranking federal agent working for Homeland Security, and we have Consuelo, the nun fighting for human rights, who looks like a meek woman but in reality is a very powerful figure who fights for families who lost their loved ones.

Religion is not the point of the film, but I couldn’t help but admire Sister Consuelo’s faith especially when so many people would think of the drug world as proof of god not existing. I wondered if the Church had made any pronouncements or was trying to help her cause in any way.

I wanted to show how her work is really rooted in her faith and I’m glad you picked up on that. That’s why I bookend the film with her, it starts with her praying, and finishes with her meditating on what she does. There’s a long tradition in Mexico of nuns and priests oriented towards social justice, the closest comparison in the US would be to someone like Dorothy Day who started as a Catholic worker and was kind of a militant and activist, but also a nun rooted in faith. At the end of the day it’s people like Consuelo who are really pushing for meaningful social justice.

We see how the three central characters in the story are all battling with internal demons of sorts, Oscar for instance, has to protect the US from illegal immigration when his own parents were immigrants. Were you interested in providing audience members with an inkling of hope?

In my previous film, Reportero, which was about journalists fighting crime and political corruption in Tijuana and Northern Mexico, in some ways that was a more optimistic film, maybe because I was newer to the issue, and partly because I kept following the journalists and admired how they kept doing their job beyond the risk. Kingdom of Shadows, in some ways is a bleaker picture, because we see reality, but if there is a ray of hope it’s with human rights activists like Sister Consuelo. I choose to close the film with the family members of missing people because to me, more than any words, just looking at their faces and seeing a combination of profound sadness married with their push for justice is the hope. These families could’ve easily given up, but instead they have agency, they have not given up.

What do you think should be the responsibility of film and art, when are so often told by Hollywood that movies are escapism?

What do you think should be the responsibility of film and art, when are so often told by Hollywood that movies are escapism?

Media can be a lot like food, you should have a variety of options. We have a need for entertainment and there’s nothing wrong with that, but I’m hopeful because there’s a growing appetite for documentaries, they’re getting better promotion, people are talking about them more. I feel this has to do with people’s need to be informed, as journalism has changed, documentary filmmaking has taken on telling stories in a more cinematic way. To me, there’s a whole part of the film universe that’s expanding, and there are audiences who want to see films like this. The fact that we’re opening in four US cities and will also be on digital platforms speaks a lot, a few years ago a film like this wouldn’t have received such a robust distribution. My responsibility and role are to tell difficult stories in a cinematic way.

You mentioned how entertainment products that touch on similar subject matters tend to be sensational, and in fact I feel they often rely on shock value. While we see some terrible things in your film, it never feels like you’re looking to exploit these elements, how did you draw the line about what you could show people or not?

I work closely with my editor Carla Gutierrez, but I think we are so bombarded by exploitative images of violence that unfortunately they lose impact. There’s a lot of rubbernecking or films that highlight the gore. I certainly viewed a lot of that material, I saw horrific scenes, but I don’t see a value in showing that. Partly of what I wanted to communicate in the film was a sense of dread and tension, through most of the film you don’t know something terrible is going to happen. It’s like a slow boil, and I wanted to recreate that sense of “not knowing” which can be even more terrible.

Mexican and Latin American culture have historically been very matriarchal, despite the machismo and chauvinism, we see grandmothers raising their grandchildren, single mothers raising kids because their father abandoned them...and with so many young men joining the drug cartels, or being murdered by drug traffickers, it’s mostly women who are left at home, looking for and after their children, husbands, friends. Even though this is obviously not the way you’d want to start a feminist movement, did you get a sense that this absence of men is helping empower women in society?

Fascinatingly enough the mothers of the disappeared, Virginia Buenrostro for instance, who is a mother you see talking to Sister Consuelo about the possible murder of her daughter, is one of many women who have become politically emboldened and empowered through this horrible process. In part because of this horrific tragedy of losing children, they are pushed into leadership roles. Virginia has become politicized, she’s now a public speaker and that’s fascinating. I think you’re right in how we see this interesting thing happen, and it’s something we’ve seen before in conflicts in Chile, Argentina, in El Salvador, where women took political roles in this fight. As the conflict unfolds it’s women who push for social justice. It’s not a coincidence that in the film Sister Consuelo says “it’s mostly mothers” in this movement.

Kingdom of Shadows opens in theaters on November 20.