Tom Sachs’ studio and workshop in New York City is populated with golden plastic turtles, bagfuls of Yodas, vinyl records, and artists hard at work building spaceships (there's a cat named Monkey too!) It’s a land of wonder for those who prefer their amazement served with a side of melancholy, as many of the materials Sachs works with have become obsolete or old fashioned. Many of the objects used in his film A Space Program (directed by Van Neistat) sit on the shelves in the studio, tempting those who see them to want to reach out and touch. The film, chronicles the Mars landing Sachs’ team executed at the Park Avenue Armory in 2012, while paying tribute to the technique of bricolage. Building everything from fully functional cooling systems, to insulated spacesuits, the film is testament to Sachs and Neistat’s love of everything analogue. When I meet them to discuss the film, Neistat refers to themselves as “the last of the analogues”, Sachs adds that there’s nothing bad about that compared to the digital generation, “it’s just different” he explains.

“We are the last generation with a visceral, biographical relation to that world” continues Neistat, referring to a world in which the tangible was almighty, and things like tapes, records, notebooks and pens ruled our society. While Sachs believes that “there is a loss of soul, magic and specialness” in how things are done today, their film can’t help but fill analogue lovers with joy and hope. I also spoke with Sachs and Neistat about the other themes in the fim, their obsession with materials, and we pondered on what aliens might like from us.

Tom, A Space Program goes as back as 2007, how long does it usually take for you between the idea of a project and its ultimate execution?

Tom Sachs: It’s all a process, Van and I have been dicking around with this since way before 2007, we were always making spaceships, models and systems, and movies about them. There’s no typical way really, it’s not planned, what’s important for us to acknowledge when we’re working is that it’s all part of a system, our space program is real, everything is executed to such detail that it becomes real. When Van and I did our own McDonald’s in 2000, it was real too, we cooked our own fries, we had burgers, security system and everything a regular McDonald’s has, and then we did movies about the aspects of all the processes there. It’s not a plan, it’s more an authentic expression of our lives and our activities, as a result the movies happen in an organic way.

Van Neistat: But you refine a lot, for the moon program we had 24 monitors, and for Mars there were like 50 monitors. There’s really no formula though.

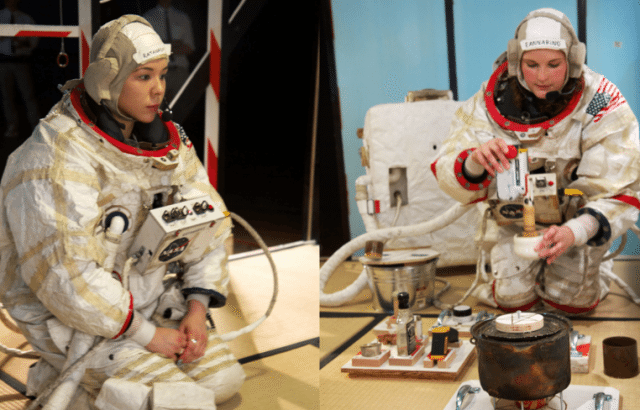

Tom Sachs: Right, the space program was done at The Park Avenue Armory for instance, and then there will be another version of it with just the tea ceremony at the Noguchi Museum in Long Island City, Space Program 2.5 if you will. In September we’re going to Europa, the moon of Jupiter, and that will be in San Francisco at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. It’s all an evolution.

Watching A Space Program reminded me of watching Ray Harryhausen movies when I was a kid, and Gumby even, I remember loving the thumbprints on the clay. Now CGI looks “real”, but it looks so real that you know it’s fake. Did you guys have a Harryhausen fixation growing up?

Tom Sachs: Those movies were terrible but I remember sitting through them because the animation sequences were so beautifully done, and I also loved David and Goliath, this evil Christian movie that was so beautifully crafted. I’ve always thought we should take one of those as a project and edit it. As a kid I watched a lot of crap because of the way it looked, I didn’t really like the politics, the Nazis for example, we love their aesthetic, not their politics. Speaking of Ray Harryhausen, we’ve always been attracted to things that show how they’re made, before Van and I started working together he was an editor of SuperScience Scholastic, and was a dedicated student of Mr. Wizard...

Van Neistat: Yeah, do you remember Mr. Wizard’s World? This guy Don Herbert, who’d actually been a bomber pilot in WWII, after the war he got a job in television in a show where he explained science principles to kids, with experiments that you could do with stuff from around your house. He would take Drano, mix it with water, take little balls of aluminum foil, drop them in there, and they will release the oxygen from the hydrogen in the water. You can fill a balloon up and make a little hydrogen bomb.

Tom Sachs: They showed that on TV?

Van Neistat: It was in one of the books, but he was the first person to have a computer and he tore apart to show how it worked. He was a huge influence, also Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, he’d do little films about things were made, like go to a factory and show a trumpet being made, or crayons. I’ve always had a mechanical brain, so it was very cool to see all of these things being made, for me those shows spoke to me in some way.

When you’re being so transparent about the process, do you become more self-aware as to the fact that you might be inspiring people to follow your path?

Van Neistat: I’m astonished that people don’t know these things. If they open the hood of a car, they don’t know how all of these little machines work, and I wonder how can they drive it?

Tom Sachs: I think what’s important to note is that whether we’re doing a sculpture or a movie, we do these things for ourselves, A Space Program is made for people like us who have never seen that, but I don’t want to talk down or up, I want to talk across.

Tom, many of your works will most likely disappear someday because they’re tangible, does making films about them in a way become a method to preserve them forever?

Tom Sachs: The movies we’ve been making since 2000 have demonstrated the aspects of the sculpture that exist in time, A Space Program is how we interact with these objects and use them for space travel, but if we go into a gallery or museum and see them, they’re just inert objects. When you make a movie about them they’re alive. When you go to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, everything in there was made for a guy like me for a rich white guy, like a Pharaoh, except the things in the African department which were made by someone like me for other people like me. By the user for the user, not in service or part of a ritual activity, it’s the metaphor of hammer, if it’s on a pedestal it’s a sculpture, if you swing it, it’s a tool.

A Space Program is in service of answering the big questions: are we alone? Where do we come from? But it’s also a tool for our making and understanding of analog culture, that these things are made by people. Van and I tried to make perfect things once, and we became frustrated that we weren’t able to do things like Apple computers, but we were impressed that Apple couldn’t make anything as flawed and human, and filled with fingerprints as a Ray Harryhausen special effect. We’ve been lucky to be able to show the flaws in our process. We had an argument about this because there’s a visible pixel in every shot in the film.

Van Neistat: At the very bottom there’s a red pixel that’s blown out in my camera.

Tom Sachs: And we kept it, our color corrector got rid of it, and we had to go back and put it in.

Van Neistat: When I started working here I didn’t know much about art, I was about 26 years old and I got what everything was, everything talked to me. There’s little signs at the Met that say “do not touch works of art”, and I believe in that, they shouldn’t be touched by unauthorized people because they’re supposed to last for a long time, but the things Tom makes, part of what informs how they look is that they must work at least once. In the movies we show how they work, so this film was a culmination of our works because it was a sophisticated piece. I think of it as one big system, you needed an hour just to show how it worked, you didn’t even need to add a story, just show how things worked.

I liked the moment in the film where astrobiologist Kevin P. Hand, talks about “the search for life beyond earth”, and says “if we don’t discover life in our solar system in the next 30 years, I may have to return to organized religion”...

Van Neistat: He wrote that! He’s a real astrobiologist, he’s a real NASA guy and he actually said that! He came in and told us he knew what he wanted to say, and we were like “yes please”.

I like that both in this statement, and in the film itself there is a constant battle of sorts between the spiritual and the scientific, and I wondered if this struggle was an essential part of your worldview as well?

Van Neistat: Tom, you say that your religion is science.

Tom Sachs: It’s not a struggle, but you nailed it, hail Sagan! Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proofs.

Van Neistat: I like religions, they’re neat, and there’s lots of crazy cool shit you get from them, I think that for the most part, all religions, including science, have the same story, but they’re told in different languages. A quantum physicist says in the beginning there was the Big Bang, the Bible says in the beginning there was light, they’re the same things, told in different ways for different brains and cultures. The big Buddhists right now are hanging out with the quantum guys, they have these thousands of years of teachings that say exactly the same thing they’re saying. To me that is mindblowing. When you look at something that’s really, really far away, it has the tendency to look like something that you look at that’s very, very, very close. A picture of synapses in the brain, looks exactly like pictures from the Hubble telescope.

Say life on other planets discovers us instead, what do you think will they admire from our civilization?

Van Neistat: Music!

Tom Sachs: But it depends if they’re stronger or weaker than us.

Van Neistat: If they come here it means they’re stronger and smarter.

Tom Sachs: The greatest things we’ve created on Earth is the art of the African diaspora, they’d look at Fela Kuti, James Brown and Michael Jackson and Outkast and be impressed.

Van Neistat: Did you hear that story about how they discovered Einstein was right and gravity is a wave? When they heard the wave it’s a middle C, that’s mind blowing! Boooom, that’s gravity! Music help fetuses, it helps plants grow better, it’s like a weird truth.

Tom Sachs: It’s the one drug I’ve used successfully to change my mood.

A Space Program will open theatrically in New York at the Metrograph Theater on March 18, 2016. See Tom Sachs: Tea Ceremony at the Noguchi Museum starting March 23, and Tom Sachs: Boombox Retrospective, 1999-2016 at the Brooklyn Museum starting April 21.