Letters from Baghdad opens with a title cards that tell us how the tragedy of the present-day Middle East began a century ago, and how “one woman was at the center of it all.” This woman, Gertrude Bell, was a brilliant adventure-woman whose expertise was instrumental in the establishment of the state of Iraq. As usual, a woman has been denied the historical credit she is owed, this time for how the Middle East was divvied up after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. But would it be wrong to ask if maybe we should let men keep taking credit for this one?

Luckily, directors Sabine Krayenbühl and Zeva Oelbaum have made a documentary with enough detail on both its subject and its setting that such fears are mostly allayed. Letters from Baghdad certainly corrects an unfair erasure from popular history, but beyond this main thrust, it is more subtle. Bell’s own analysis of Iraqi politics is sophisticated enough to edify the modern viewer, and the documentary’s position on her gender is complex. You’ll walk away from this documentary smarter, not reeling in falsely inflated triumphant zeal.

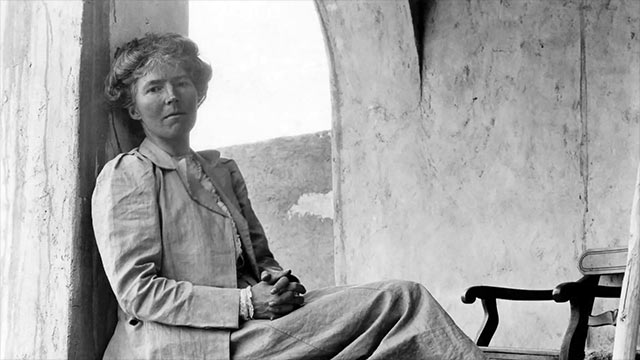

The movie covers her birth to a wealthy, lord-of-industry family, her education at Oxford, early whimsical travels in the Middle East, and her growing involvement with the creation of the state of Iraq. It is all told entirely from the voices of primary sources with actors actually playing the characters as though they are talking to the camera, except for Tilda Swinton who voices but does not portray Bell herself.

As the story unfolds, we see she was a woman who had to settle for infamy over recognition or respect. Early in her travels, she delighted at having become “a person” in the Middle East, by virtue of becoming an object of the Ottoman Empire’s suspicion. But as she grew in power and prestige, the reception remained the same. She either garnered distrust as a mysterious woman in power or praise in the manner of a circus sideshow.

Persistent adversity seems to have eventually cultivated a distaste for her own sex. She joked about needing a wife to keep house, and she gained a reputation for being rude to women she regarded as the uneducated. But when you hear Lawrence (“of Arabia”) go from evaluating her attractiveness (“not beautiful, except with a veil on”) to expounding on how he silenced her by “squash[ing] her with a display of erudition”, it takes a cooler head than mine to not forgive her her tone-deaf quips and occasional cruelties.

Terse as she could be, though, she had bottomless affection for her father. I assume there are no surviving copies of his letters, because we never hear his responses. This inadvertently creates the disturbing effect of Bell continually lavishing loving praise on a mute recipient. It comes off as an accidentally apt metaphor for a life of restless, thankless adventure: love letters to a father, cried out into a void. So much effort with so little reward.