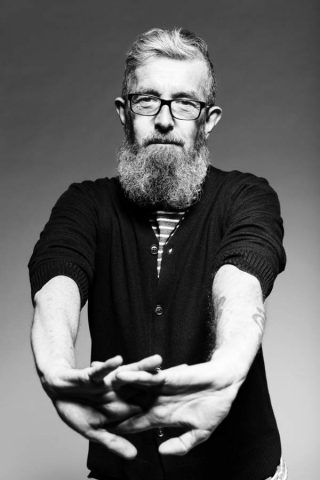

Though director and educator Les Waters hails from across the pond, he’s made quite a splash in the American theatre scene in the past several decades, bouncing from the west coast — where he served as head of the M.F.A. directing program at UC San Diego and the associate artistic director of Berkeley Repertory Theatre — to the south, where he’s spent half a decade as the artistic director of the Actors Theatre in Louisville, Kentucky.

During his tenure in Louisville, Waters has reasserted the importance of the Actors Theatre’s annual Humana Festival of New American Plays, championing (and stepping in as director for) some of the preeminent playwrights working today. This season, not far on the heels of Lucas Hnath's The Christians, which Waters brought from Humana to Playwrights Horizons in 2015, he returns to Playwrights with another Humana-born project, Sarah Ruhl's For Peter Pan on Her 70th Birthday.

His fifth collaboration with Ruhl, For Peter Pan is a cerebral yet sentimental piece that flirts with whimsy as it reckons with the reality of growing old. Kathleen Chalfant leads a stellar cast as Annie, the eldest of five siblings who reunite at their father’s death bed to drink whiskey, playfully spar about the current climate and find solace in fond memories of their tight-knit Irish-Catholic upbringing — especially Annie’s once-upon-a-time star turn as Peter Pan.

Soon, Waters will return to Louisville, where he'll work on an Actors Theatre production of Little Bunny Foo Foo, written by Anne Washburn and featuring music by Dave Malloy. But before he leaves Gotham — if we’re lucky, he'll return again soon — we had the chance to chat with the director about his creative relationship with Ruhl, what it’s like to live with a play over multiple productions, and the time-warping power of theatre.

So tell me a bit about how you got involved with the project.

So tell me a bit about how you got involved with the project.

It's the fifth project that Sarah and I have worked together on, and it was a commission. When I became the artistic director of the Actors Theatre in Louisville — I took over in 2012 — one of the first things I did was I asked Sarah if she would like a commission, and she graciously said yes. She talked about writing a piece about people who lived in a small town and worked had performed in Peter Pan, and that was the initial idea. I wasn't heavily involved in the commission, but she would tell me how it was progressing and told me along the way that she was interviewing members of her family and that her mother had actually reformed in Peter Pan.

We premiered it at the Humana Festival in 2015, then did it again at Berkeley Rep, where I used to work, last year, and this is the third version of it with most of the same people. Danny Jenkins is new to the production, although he did a workshop of it before, and it's got a new set design, but it's basically the same team working on the show.

What is your collaboration process with Sarah like?

We don't have an intense back and forth; we have a pretty free and easy relationship. I'm not a particularly hands on director while someone's writing a piece. We do talk about the material -- we talk about the material particularly during workshops -- but I have complete trust in Sarah, and I adore working with her, so that was the basis of the collaboration.

What has drawn you back to Playwrights Horizons?

I think because Playwrights has been extraordinarily generous, and opened its arms to the festival and said, 'We've enjoyed these shows, please bring them to New York.' The last one was Lucas Hnath's The Christians, which was also a commission at Actors Theatre. So it's been an act of generosity on their part and a pleasure to do them.

What do you notice is different about this performance than the previous incarnations of the play?

I think the family home is more physical in this production; it's there on stage all the time and transforms in part three.

Is that something you've been trying to draw from the play for a while?

I think it's something that revealed itself in the process.

It must be interesting to work with a play in so many different spaces...

Yeah, it is. It's a luxury. Many new plays have one production, and that's it. So the opportunity to kind of get back in there and dig in again is really useful and very enjoyable, especially if you're working with the same group of people.

Did you find yourself wanting to make changes?

I think mostly it comes together in the same way, but you find depths to the material that you hadn't seen before. And I think the actors lead the way into that. Although there are moments in this production that we thought it would be interesting to do this time that we never did before, but I think the real exploration of the work is done by the team of actors.

It's so critical for the script that the ensemble presents as a family, and that seems so effortless. How did you help create that bond?

Oh, I credit the actors with that. I think I did my job, but I think that there’s a level of skill and a level of trust between these particular performers — and they delight in performing with each other.

I mean, the grand tradition of the Great American Family Drama is, over Thanksgiving or some holiday, the family will meet up and tear each other apart, and secrets are revealed. So this is an anti-family drama in a way. You know, they have an argument about politics, but this is a family that actually functions rather well and loves each other, so it needs a level of trust in the playing — because its action is different than most family dramas.

The characters are also very complex. They each have to shift between adult and child, real and pretend. How did you draw out the balance?

I think the shifts between being an adult and a child are most evident in part three when they're dreaming or acting out a version of Peter Pan, and that was a real exploration during this iteration of the play — something we've never really explored before, which is part of the delight of doing it for the third time — where they would switch rapidly backwards and forwards between being an 8 year old and a 64 year old, and it has to be done at breakneck speed, and they're not even aware that they're doing it. I have to say, that was a late discovery in the playing of it, and I think it has enriched the production enormously. The rest is the usual status battles that happen between siblings that happen according to where you are in the lineup, whether you're the oldest or the middle child.

The play seems to posit that, in many ways, the theater is Neverland. It’s a place where you never have to grow up. Do you agree?

Well, I do really. I think the theater is a metaphor. I mean, language is a metaphor. Whether you're doing it or watching it — and if you're watching it you're doing, it in a way. You're sitting there and participating in this act of imagination. And an 80-year-old person could walk onstage and say "I'm the 6 year old king of Romania," and the moment they say it, you believe it, although you're looking at somebody very old.

People onstage die and then they resurrect and they appear at the curtain call. I think theater plays tricks with time all of the time. In the course of two hours, you can go through somebody's life — but it's only two hours. You can watch a piece of theater that you don't like and think, “Oh my god, that's ninety minutes I'll never get back" or “That felt like ten hours." I recently watched Tony Kushner's Angels in America: The Millennium Approaches at Actors Theatre, which is three hours long and it felt like an hour and 20. So it's a very loaded, metaphorical place to inhabit.

What do you see next for the play? Another performance in another space?

I have no idea. No idea. I have to say, I would be very happy to do it again. It gives me a pleasure to work on it. It's a great gift to have been able to work on it.