Banksy Does New York, from director Chris Moukarbel, is not a film about Banksy. If you are looking for the answers to all of your burning questions about his (or her) private life, favorite meal, or biggest fear, keep looking. What this film is, is a searing look at art culture, the wealth gap, and social media through the lens of Banksy’s self-proclaimed “residency” in New York.

In October of 2013, Bansky landed in Manhattan with the objective of revealing a new piece of street art every day for a month. The location of each piece was announced through a vague image of the work on Banksy’s Instagram each morning, thus sparking a month-long, city-wide scavenger hunt. Banksy Does New York examines the effect of the “Banksy phenomenon” on New Yorkers.

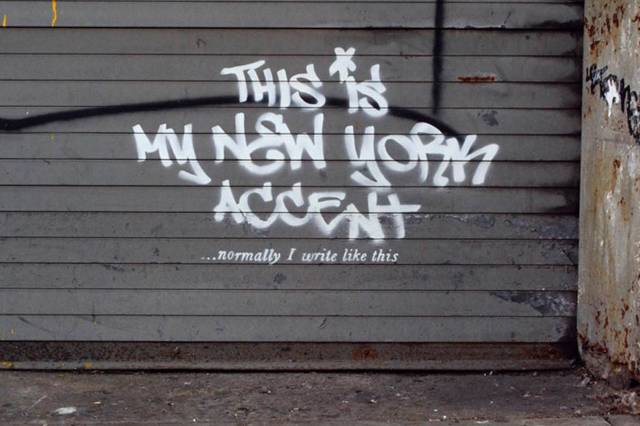

Many nay-sayers will claim that the scavenger hunt was a social media stunt, and that may be true, but its result was a month of heightened social awareness in all five boroughs. The film explores three levels on which the Banksy residency operated: individual, social, and online. Banksy’s work is anchored firmly at the crux of fine art and graffiti; it is art for the masses, pop art in the public sphere. With the help of many years of a carefully cultivated image, Banksy has positioned him/herself in the ideal spot for spreading messages.

Individual experience is portrayed in the film predominately through two dog walkers/Banksy hunters who recorded their travels throughout the 30 days. They are a good representation of the “everyman,” and adorably refer to Banksy as “Ban-sky.” These two are clearly in it for the game and little else. Through social media, they tracked the pieces each day in the hopes of getting there before they were ruined or stolen. Lightening fast online Banksy-tracking added another layer of interaction, making the residency almost collaborative. A repurposing of Banksy through the public eye (a similar concept to Coca-Cola’s “Share a Coke” campaign). The constant Instagramming provided documentation of the pieces as they were discovered and then destroyed.

This destruction of the works is the negative end of the individual experience. It is the unwelcoming New York that some might have expected. It is Mayor Bloomburg irate, cops challenged, graffiti artists spot-jockying, art critics eyerolling, and East New Yorkers charging $5 to Manhattan-ites for a picture of their local Banksy work. But the controversy almost seems intentional. As the film cycles through each October day, each individual reaction highlights something unique in the residency, something to do with social issues, be it an aggression towards the systematic oppression (or whiting out, as in 5 Pointz or the MTA) of street art in NYC, the privatization of art in general (as in the attempted resale of Banksy work in South Hampton), or those very gentrifiers who paid a rare visit to Queens.

Banksy Does New York does an excellent job of exploring these issues through the three-realm structure. The film uses the residency almost as a tool, or perhaps highlights that Banksy wishes to be a tool, for opening discussion. And open it, it does. Although the film offers no concrete resolutions, one leaves the theater with an altered perspective on art and its position in the world, on our walls, and on the street.