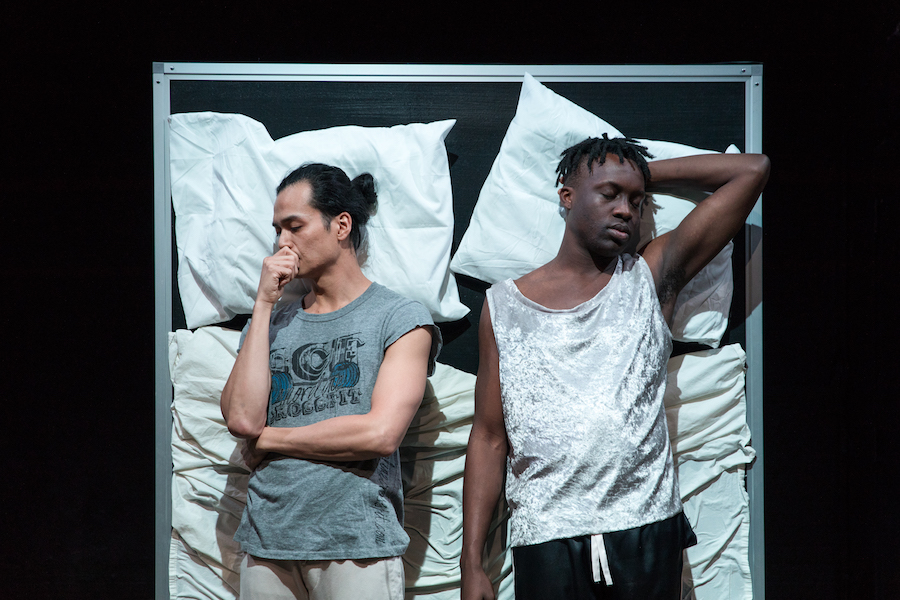

Kyoung H. Park’s PILLOWTALK centers on Buck (JP Moraga) and Sam (Basit Shittu), interracial newlyweds who are trying to find their space in a society where their existence is still a political matter. One night after work they find themselves negotiating how their sexual desires, personal needs, and emotions are framed around the notion that they live like outsiders, always trying to look in. Park’s sensitive dialogues and his sense of timing allow for Buck and Sam to go from engaging in explosive debates, to, literally, swooning, as the play allows for dance interludes to speak what the characters can’t bring themselves to express in words. Park makes peacemaking theatre, which he explains as being art made not in direct opposition to war, but a response to the violence legitimized by systems of oppression made acceptable by our culture. It’s through culture where Park believes artists can make a difference. The issues in PILLOWTALK certainly fit the description, and the conversations that should be sparked by the play will only confirm this. We spoke to the playwright about the themes in PILLOWTALK, his interest in addressing intersectionality, and creating dramatic archetypes for people of color.

The play is so sad that I had to watch Pretty Woman as a sort of antidote after reading it. Why was it important for you to write something so truthful and in being so, even hurtful?

I started writing the play the year marriage equality was passed, I was very involved with queer activism, with the gay Asian American community and the intersectionality was at the front of my mind. I wanted to write a play because until that moment I had never, as a gay person, considered marriage as a possibility in my life. When things changed so dramatically I wanted to figure out what was the human experience of something so personal to me, and so political in society. In trying to humanize the relationship between the characters in the play all these conversations appeared, I found I was exploring very hard topics to discuss. I didn’t mean for it to be so emotional, but I did want to honor and humanize the struggle. Being involved in community I knew marriage equality was a celebratory moment, but there were still many issues that needed to be addressed.

The idea of marriage as a fairy tale ending was far from true. With marriage equality it was also true that the needs of people of color were far from done. Our issues are always at risk like one of the characters points out in the play. Can you expand on this?

I read “Against Marriage,” an essay by Bruce Benderson which critiqued marriage equality based on how it’s changed the idea of queer activism. It was a very radical essay that I kept coming back to as I wrote the play.Benderson talks about how marriage equality as an issue creates a more centerist platform that marginalizes [cut to] people of color, trans people of color, minorities, people that don’t conform to the heteronormativity of marriage or structures that reinforce patriarchy. At a conference at the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies, called “After Marriage,” we had a long-table conversation about post-gay marriage politics and we realized that a lot of the issues that people of color face, like immigration, racism, work discrimination, mental health, were privatized. Once marriage equality passed these issues didn’t become part of the public discourse, they were privatized.

How do you balance the need of addressing the rightful rage of the characters, with something that won’t feel like it’s hitting the audience on the head with a hammer?

I started writing plays after 9/11 and I realized my tendency was to write really political plays and I’ve kept tackling political issues trying to make them dramatic without making them propaganda or agitprop. The subject matter of my plays is political, but I know political theatre has resistance from the audience and critics. When I write plays I’m mindful of those sensitivities, I want people to see the plays. The other thing is, this play was originally a reflection of the issues I was having with my partner, and when we workshopped it, the actors’ input became part of the characters. We talked about love and our thoughts on marriage; that nuance is now reflected in the characters. The play is about a relationship, so whether you’re straight or gay, black or white, these are conversations you might know.

The play made me think of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and considering you’re a founding member of The Sol Project, which seeks to create a new canon of plays by Latinx writers, I wonder if at any moment you thought about Buck and Sam years in the future being archetypes in the same way George and Martha from Woolf are?

We talked about this a lot in the room. I think my work has always come from a very personal source, but as an artist of color there’s always been an inherent responsibility to give voice and to shed light on experiences that are not represented onstage. Even in the narrative of gay stories being produced in theaters, the white gay male experience is predominant, so in this play I wanted to be very conscious of how gay and racial discourses need to intersect. The Asian identity has always been at the center of my work, so when I was invited to be part of The Sol Project it was the first time I was asked to join a Latinx space; I identify as Latino because I’m from Santiago, Chile, but because of my Asian face I wasn’t invited to these other spaces in New York. People of color are always pitted against each other, made to fight for that “other” slot. The play has also allowed me to come into African American spaces, because the plays delves so deeply into race-related issues, and when you add ballet into the conversation, it opens up yet another space, because bodies of color are rarely represented in this type of art form.

You started writing the play before the 2016 election, did writing it make you feel like you’d be able to exorcise your demons by putting them on the page, would “the worst” not happen if you wrote about it?

I don’t think many of us could anticipate what would happen, but even as we developed the piece in the Obama years, the fact that we were addressing issues of race made me feel like we were critiquing the idea that we lived in a post-racial world. When Black Lives Matter began, the Asian American community in particular, had to confront how racism exists within our own community. Writing the play, it felt myopic to celebrate marriage equality when all these tragedies were happening all over the country. In PILLOWTALK, we’re challenging the notion that democracy works if it only works for certain people.

As a playwright of color what do you think is lost when only white critics review your work?

As empowering as it is for us to be artists of color telling the stories of queer people of color, in reality even we as people of color have internalized white supremacy, white standards of beauty, or European centric ways of artmaking. Premiering this story, we are exposing ourselves to whiter audience. In the set design by Marie Yokoyama, we purposefully set the play within white frames. I see these frames as the frames of the male white gaze, the gay white gaze, and the gaze of white supremacy. I’m cognizant that we are still being viewed from this lens. We’re making this very visible to at least acknowledge that these systems of oppression aren’t abstract, they’re tangible and they’re present in the room with us. It’s about negotiating our relationship within that space.

For more information on PILLOWTALK click here.