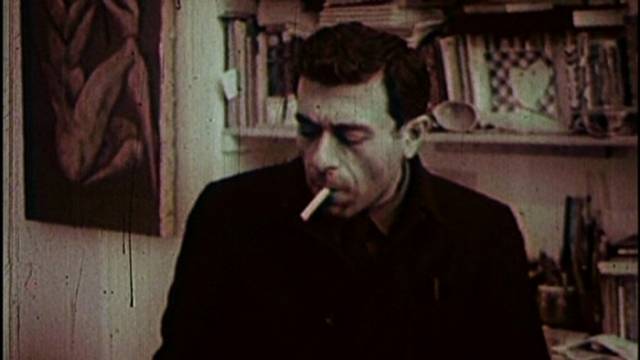

Few modern artists are shrouded in as much mystery as the Iranian Bahman Mohassess. Born in Rasht in 1931, he would go on to become one of his country's most prolific creators, having done paintings (he's sometimes regarded as the "Persian Picasso"), sculptures and theater (he translated and staged the works of Luigi Pirandello and Jean Genet among others). Living in a country where repression became the status quo, he went into exile on a couple of occasions, eventually leaving for once and for all in the year 2006, after the death of his brother. He moved to Italy where he lived in practical anonymity.

Enter filmmaker Mitra Farahani, the acclaimed director of Just a Woman which won the Teddy at the Berlinale in 2002, who found Mohassess and proceeded to make a documentary about his life, leading all the way to the last two months of his life (he died in 2010). In Fifi Howls from Happiness, Farahani captures a man who is contradictory, complex and endlessly fascinating. His remarks on art, life and politics are incendiary and will make you hope he had been around longer to talk more and to make more art. Fifi Howls From Happiness premiered at the 2013 Berlinale and is now making its theatrical debut in the United States. To mark the occasion, Farahani was kind enough to answer some questions we had about her film and subject.

How did you first become interested in Bahman Mohassess?

The story of Bahman Mohassess was known to most Iranians who at least have heard about art and literature. It’s not his symbolic importance, acknowledgement or fame that was lacking but his physical presence. He would always be referred to rather as a myth or a living legend than an actually existing person. Mohassess’ works function in such a way that his fishes and still lives are looking out there to the world, a cynical and crude look. Thus the “creator” of such “creatures” should embody such a look to the world himself. I wanted to find the disappeared body behind this very peculiar look.

Can you elaborate on the process of finding him after he’d been in exile for so long?

Sorry, I won’t explain it as I didn’t it in the film. But we can have a coffee and I’ll tell you.

Bahman declares that “democracy is just as rotten as dictatorship”, did you discover any political movement he actually admired? Did he talk about an ideal system?

He used to say, as an aphorism : “The Iranian is not partisan, he is biologically monarchic. The Italian is not Christian, he is biologically Catholic”. He was not in favour of this or that specific system, but he often condemned people for getting the political regime they deserved.

The Bahman we see in the film has a smart, complex quote for everything. Did he come up with these on the spot or would the two of you discuss what the shoot for the day would be like to help him prepare his speeches?

This question gives me a good laugh! How could one believe that Mohassess would even repeat anything twice, or “prepare” anything? Men of History are those whose spirit and speech impose themselves naturally. It’s their entire life that could be summed up in a series of aphorisms.

The film is mostly confined to the one room where he spent his last days, and he even talks of it as being his “world”. How receptive was he of having a camera capture his space?

Sometimes it would disturb him, not because the camera would unveil his space or world but because it would denature the human relationship taking place there.

Bahman proudly talks about how he destroyed his own works. As an artist did you feel identified with this? Who do you think “owns” the art once it’s out in the world?

Yes, I quite relate to his attitude towards the possible destruction of one’s own works and especially in terms of safeguarding my own right to do whatever suits me with my own creation. On a more global perspective, if all anniversaries entail a certain funeral, I guess creation and destruction can’t go separate. But at the same time, I believe that as soon as someone collects, buys or appropriates a work, in any manner, and overtly takes moral responsibility for it, the work is his/hers. Indeed Mohassess only destroyed works still belonging to himself, not those belonging to others.

He also says that the beauty of homosexuality was in its prohibition. How easy/hard was it for you as a filmmaker to include these bouts of internalized homophobia in your film? Do you think his views would have changed if he'd lived longer?

I guess in what you would call a “democracy”, one should be able to speak his mind regarding sexual and social beliefs that he experienced, without being accused of homophobia. Obviously he wouldn’t have changed opinion since he meant what he said. This remark, to me, feels exactly the same than some Iranian conservative who actually asked me: “Why did you feel it was necessary to include his quotes on being homosexual? People don’t need to know that.”

The film is so complex that it can be seen as a “cautionary tale” (this is what repression does to you) and also as an exemplary feat of heroism (Bahman remained true to himself until the very end). How did you find the perfect tone for your film?

What happens when you enter this two-month shooting, with its characters and self-imposing intrigue, each of the persons involved (Mohassess, Rokni, Ramin, myself) feels the situation according to themselves. Sincerity was anyway so crucial to this situation that each character had to play his most “sincere” part. My own part eventually became the most difficult, since it didn’t end with this shooting. I had to pursue this sincerity during the whole editing process of the film which took a year and a half.

Can you talk about using The Leopard to expand on the themes in the film? Where there are any other films you would've used if this one hadn't been available for example?

It came through Mohassess own spontaneous inclusion of the The Leopard – which was a good surprise. But another film that he showed to us was a feature film on Leonardo da Vinci’s life. I could have included some insights of it, since he identified so much with the utopia of Renaissance (and held a reproduction self-portrait of Leonardo in his wallet).

Can you discuss scenes you left out and the overall process of editing?

I started reducing the first cut out of a four hour version! The final film lasting one hour and a half, I can recall the others two hours and half, for you, in a longer occasion. Seriously, I had to leave out a lot of aphorisms and remarkable memories of his. It’s almost like a “ghost film” existed beside the real one. The editing process was definitely a tough experience, in order to find the right “collage” out of this nonstandard character.

What do you want people to take from the film?

The same than what remained for me from him, when he asked “how come you don’t know Jan Palach?” pointing at my ignorance of this or that historical fact or event. Be less ignorant towards history.

Fifi Howls From Happiness opens at the cinemas in Lincoln Plaza in New York City on August 8.