Interstellar takes place in a future where planet Earth has turned into a wasteland and people are on the brink of extinction, as one of the characters succinctly puts it, “the last people to starve will be the first to suffocate”. But somewhere in this Dorothea Lange diorama there is someone who can make a difference and save the planet, or at least its inhabitants. Enter widower Coop (Matthew McConaughey), a former pilot who has given up on his dreams because there is no use for engineers in a planet desperately craving farmers. By some design of nature, Coop ends up discovering a secret NASA base, where the last scientists on Earth are working on a plan that might just be their last resource: they will send explorers to find a new habitable planet beyond the confines of the Milky Way. Luckily for Coop, the program is run by his former professor, Brand (Michael Caine) who immediately gives him the job as pilot, unluckily, he has to leave his two children behind, promising them he will return, which might very well be wishful thinking.

Interstellar takes place in a future where planet Earth has turned into a wasteland and people are on the brink of extinction, as one of the characters succinctly puts it, “the last people to starve will be the first to suffocate”. But somewhere in this Dorothea Lange diorama there is someone who can make a difference and save the planet, or at least its inhabitants. Enter widower Coop (Matthew McConaughey), a former pilot who has given up on his dreams because there is no use for engineers in a planet desperately craving farmers. By some design of nature, Coop ends up discovering a secret NASA base, where the last scientists on Earth are working on a plan that might just be their last resource: they will send explorers to find a new habitable planet beyond the confines of the Milky Way. Luckily for Coop, the program is run by his former professor, Brand (Michael Caine) who immediately gives him the job as pilot, unluckily, he has to leave his two children behind, promising them he will return, which might very well be wishful thinking.

That is pretty much all one needs to know about Interstellar, given that the plot is quite convoluted and often nonsensical, even for a Christopher Nolan film. The real wonder here being that for once, it doesn’t matter! Interstellar is the first of his films since Memento where he doesn’t allow genre conventions and grandiose, if inefficient, world-making to swallow him whole. In fact, he goes ahead and acknowledges these plot holes and inconsistencies with various winks scattered throughout the screenplay (which he co-wrote with his brother Jonathan). For most of the decade, Nolan has been delivering epic fantasy and sci-fi extravaganzas that feel like going to a party to which you weren’t invited. The Batman films and Inception were cryptic, too opaque for their own good, and made people believe like they were concealing grand truths because of the way in which they were packaged.

The truth is that the only truth is that it was Nolan all along who was unsure of what he was trying to say, and in Interstellar he’s basically going the Socratic way by affirming that all he knows is he knows nothing. This seemingly simple revelation allows him to become more playful, to worry less about the importance of his ideas, and more about the emotional impact he can have in audiences. Turns out he wasn’t really trying to be Stanley Kubrick, but ‘70s Steven Spielberg, a warm-hearted director with an eye for spectacle. There are plot elements in this film straight out of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and throughout, we see his obtuse formalism give path to something more inviting.

It certainly helps that the film was lensed by Hoyte van Hoytema (Her and Let the Right One In), and who, unlike Nolan’s usual collaborator Wally Pfister, has an eye for finding humanity within the labyrinths of “genre”. Most of the outer space scenes in this film, feel like they were done by the same team behind 2001: A Space Odyssey; there are balletic sequences and astonishingly gorgeous space landscapes that remind us why Kubrick’s film remains timeless: he knew that since it was unlikely any of us would actually go into space, he could forgo realism in search of something oneiric. Nolan too turns the unknown into his canvas.

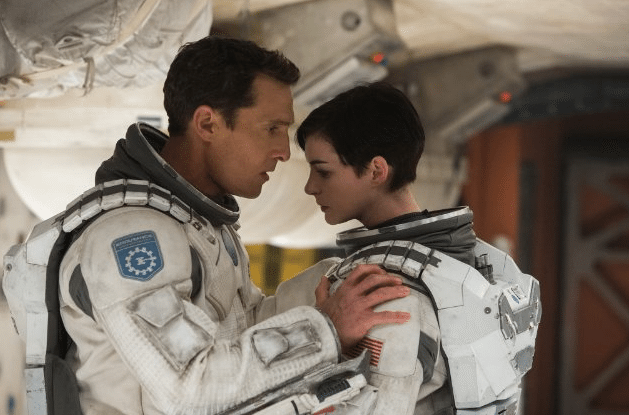

At the center of the film there is also a fascinating dialogue about whether we should put more importance on faith or science. As agnostic as Nolan wishes to remain, he finally reveals himself to be a devotee of romanticism, he doesn’t emphasize any specific religion, but makes a film that’s all about the importance of love. “Love isn’t something we invented” explains Coop’s fellow space traveler Amelia (an extraordinary Anne Hathaway), it could be “an artifact of a higher dimension, love is the one thing we’re capable of perceiving that trespasses dimensions of space and time”, she finishes. Where in other Nolan films this kind of line would seem parodic, it works in Interstellar because this isn’t a space epic but an intergalactic melodrama that riffs on classics like To Kill a Mockingbird.

Interstellar is by far Christopher Nolan’s less restrictive work, it shifts tonally and visually (the back-and-forth format change from IMAX to 35mm can be distracting) and it doesn’t always work; yet, ironically it feels like the debut of a filmmaker we thought we knew. From Hans Zimmer’s organ-infused score, to the many nods to faith and fate, it’s a film about achieving spiritual bliss through creation, about seeing what we thought we knew with different eyes, about renewing the world by renewing ourselves. Nolan has finally invited us to service, and for once he's not making us worship him but next to him.