This winter, Stage Left Studio is hosting an encore engagement of Margaret Morrison's critically acclaimed love story Home in Her Heart. Set in 1939, the play tells the story of American performers living in Nazi-threatened London. Claire Hicks, an African-American pianist, and white tap dancing male impersonator Jimmie LeRoy are ordered to return to America and must face the harsh reality of a segregated U.S. and a possible end to their relationship.

This fascinating tale is written by Margaret Morrison and directed by Cheryl King. Together, they have created a work that explores historical, yet timeless issues of race, gender, homosexuality. Margaret Morrison, playwright, actor, rhythm tap soloist, and dance scholar, agreed to spend some time discussing with us what it was like both writing and physicalizing the story and the complex character Jimmie LeRoy.

What has drawn you to tap dance?

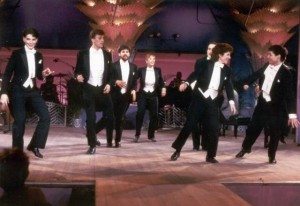

I always liked tap as a kid. In the early 1980s, I was pursuing a career and training in modern dance and I met my teacher (who would become my mentor and director) Brenda Bufalino, who formed the American Tap Dance Orchestra. I was one of her advanced students, so when she formed the company in ’86 I was one of her core dancers. It was a burgeoning time for tap dance. We call the 70’s and 80’s the Tap Dance Renaissance when tap came back full force. It’s almost like tap embraced me. I always loved it, but it’s like tap kind of reached out and offered me a home and I had all these possibilities through it and I found it endlessly fascinating. I became fascinated with tap as a practitioner: the rhythm, the music, and the ability to express myself in so many different ways because you get to be a musician, a dancer, you must be technically precise but there’s all this freedom of individual expression. It’s a very improvisational form, but we would also do choreographed group works that are very complex and musical. All this really intrigues me about tap dance.

I sort of lost interest, at that point, in pursuing my modern dance career, and the acting that I do goes back to something I had done when I was younger — in high school. I went back to acting much later. I think I was in my 30’s or 40’s by the time I went back to acting class because I really wanted to re-gain… I wanted to be able to perform on stage a different way… I wanted to say more on stage.

Yeah, I understand that. And I thought your acting was great!

Thank you! It’s my newer skill set. I am a dancer and choreographer first, then a playwright, and then an actor. And then a singer after that! The singing just kind of limps along… (laughs)

What do you find most interesting in tap dance history?

Tap dance history has all this multi-varied history of black and white American culture. And I found myself meeting all these black and white elders who were really digging the form. Tap has an interracial heritage as an African American dance form. Tap played a key role (as jazz music has) in how African American culture flourished in America and how it dispersed to every corner of American culture. As I began writing plays, I became interested what does happen when a white woman and a black woman get on stage together and you actually address the power issues that go on in our culture? I didn’t want to ignore them, I wanted to explore them. That is part of the impetus of the play. My love of tap and my love of jazz culture (because tap is a part of jazz culture) were part of what intrigued me and drove me to write the play.

I was a professional dancer in the 80’s and 90’s and dance was my form of expression — but, tap dance has, or at least at that point, was considered more of a masculine form. What always seemed odd to me was that there were all the female tap dancers now and there are all these female tap dancers of the past, but the standard of excellence was always being gauged by maleness... This is how the history books were written. So I started studying women tap dancers and that got me into women jazz musicians and as I was studying that, I was also studying male impersonators. I developed this character of Jimmie LeRoy and of course since I want to get myself on stage, I wrote write a part that I would love to play.

It’s definitely a complex character. And, it’s a fascinating character. Is the character what got you into playwriting?

Well, as a dancer I get to express myself nonverbally, and I certainly get to express myself musically as a tap dancer, but I really felt like I wanted my performance pieces to say more, so I started writing. Then, as I started writing text to go with my tap dancing I started writing plays and characters. First it was just going to be me, Margaret — that was the original concept when I began writing — then I started writing these characters who could explore these issues with much greater complexity. I’ve always been an independent performing artist and am very lucky I got to dance with several companies, I got to tour the world, and I still work for the American Tap Dance Foundation, but at a certain point in your career you want to do your own work. You want to have your own voice. And you can’t just wait for someone to knock on your door. You must produce your own concerts; you must create your own work to get your voice out there. I was really driven to create my own work because I wanted to see these types of stories on stage. I wanted people to see these types of women on stage. I wanted to portray these types of women and address these types of issues. I felt very driven to write it, and you know, once you start it, ya gotta finish it!

What about your character do you most connect with, and what you do struggle to connect with?

I am fascinated with what I would term female masculinity. These women identify as females. They do not identify as transgendered. They live their lives as females, but they have an extremely masculine energy. They are the “butch” women. I am deeply fascinated with butch culture, female masculinity…

I started studying male impersonators, who have a long and important history in American performance (very popular in the 1900’s to 20’s). They weren’t always necessarily lesbians. It was a very popular performance form and people loved it. It would be this tour de force when the actress could be the dramatic female role, and then she would come out in the next scene and would be in a pants role. Nowadays there are drag kings who are very tied in with queer culture, lesbian culture, but back in the day it wasn’t necessarily part of sexual identity.

Since I’m interested in female masculinity, I wanted to take that on. Jimmie LeRoy is both a lesbian and butch in her life. She the more masculine acting one of the pair and she also dresses as a man on stage. She prefers to wear trousers on the street, and she dresses in a skirt when she must — when it is required of her.

What was it like taking on this role?

It’s hard to act like a man. I had to get some coaching for it (laughs). And my director worked on that with me as well. I had to retrain my way of standing, I had to retrain how I held my shoulders, I studied masculine women, and I got some coaching from some friends of mine, which was kind of funny and wonderful. Really, really quite wonderful, because that’s not actually how I go through life. I’m actually am a relatively feminine-identified woman. I don’t wear lots of make-up and I don’t wear high heels and skirts because I find them inconvenient, but I am kind of more feminine identified in my day-to-day life.

And there are other things about the character too. The character…she’s a mess! She’s demanding, and she’s controlling, and she knows she shouldn’t be and has to keep on being put in her place. And, she keeps trying to control circumstances she can’t control. Jimmie LeRoy is so complicated because she is saying 'this is not my war'. This war doesn’t concern me. Well, in fact, at this time in 1939, this was everyone’s war. And as an American Jew, this was her war. She tries to stick her head in the sand, but she cannot. And, Claire, the African American character, is there to say, you cannot stick your head in the sand. You have to face reality. Or, at least, you can’t tell me to stick my head in the sand, because I’m black and I cannot walk away from Jim Crow. What I like about Jimmie LeRoy is that she has unexamined white privilege. And, I think that’s a really important issue: unexamined privilege. Racism isn’t just a problem for those who happen to be black; racism is a problem for all of us. And, I wrote this into the play, I as a white person have to take responsibility for the way the system privileges me, and disadvantages somebody else. We’re all part of the same system. Jimmie LeRoy keeps saying this is not my problem, how can you let Jim Crow rule your life? And, she’s wrong! I like playing a character that is wrong. But, she is also a dreamer, has hope, and is a good sport. So, that’s lovely, and she does learn by the end of the play, which is very gratifying.

This is such a physically rich character. On such a small stage and so close to the audience, what was it like taking this character on physically?

In my dance world, if we were told to take a movement to the right, I would move ten feet where everyone else has moved three. I’m just that kind of mover. I’m a pretty expressive person physically. It’s interesting because I don’t find that space too small. We had to adapt, but then, one does. When I am on a full stage — on a twenty by twenty stage — I’m on every inch of that stage. Here, I had like ten feet across. When I’m in the nightclub space and the curtain is drawn, and I’m in front of the curtain it’s really only three feet deep. Sometimes I had to turn profile, because I would be kicking the curtain behind me. An additional aspect of the physicality is when I come out in that nightclub scene and I address the audience, the physical audience becomes my theatrical audience. I like that also, because as a tap dancer, you do face out. It’s very presentational and you have a relationship with the audience. So…you learn to move fully but not crash into things.

I think also, as an actor, it’s a sense of fun. I came out of acting training with my teacher Carol Fox Prescott, which is also how I met Cheryl King, my director. We were both students in the same acting class. She was very much into techniques to keep the body engaged, physically engaged. Cheryl and I worked a lot on that because there is a lot that goes on in the play where there are nonverbal responses. The two characters are always interrupting each other. There’s a lot that goes on where the statement doesn’t end up being finished, so the meaning is physical. I’m a choreographer; there’s a dance going on between these women. They are pushing and pulling each other. They are trying to be self-determining, and they’re also trying to work together. It’s a touch-and-go as to whether it’s going to work. The relationship may just pull apart. There is a dance going on between them, and I physicalize that.

Now, I understand that you wrote a sequel to Home in Her Heart.

What happened was: I wrote Home in Her Heart and we had a workshop production in 2012 and 2013. I was so enamored with these characters; I started thinking of other stories. One of them turned into a twenty-five minute play, called The Loves of Miss Jimmie LeRoy. It takes place a couple years after this play with Jimmie LeRoy and her ex-lover from the past, Marjorie (who is mentioned in Home In Her Heart). Then, I was still doing the workshop production of Home in Her Heart and I was frustrated with it. I felt this isn’t right. There are things about the characters that to me aren’t tight enough, that aren’t human, that don’t make sense. Also, the original Home in Her Heart workshop production had a sad ending. That grated against me because there are lots of sad, lesbian love stories (laughs). There’s lots of literature — there’s a whole library of gay stories that are really depressing. It’s now 2015 and I actually believe, even though I have no historic evidence because these women are so under the radar, but I fully believe that a relationship like this could have existed…it would have been hard, but women fall in love with women; black people fall in love with white people in the most difficult, impossible circumstances. Somehow, something would have been worked out. Or, at least the external circumstances would be awful, but that doesn’t mean that the internal love would not have been there. So, I went back to the drawing board and I rewrote the play and rewrote the play. But, as I rewrote the play… now the play that you saw is, I think tighter and has a more positive ending, but because of that the sequel no longer holds water.

So, now I have to go back and rewrite the sequel (laughs). Because it refers to things in the first version that are not there anymore. But, basically it’s a sequel about Jimmie LeRoy, and she gets together with an ex-lover and they go over ways in which they had seriously wounded each other in the past, and ways in which they need each other in the present. You know, especially for gay men and lesbians, your ex-lovers are your family -- your community, because maybe your family of birth has rejected you or you can’t go to them for help or you have to be in the closet with them. So it’s really your community of friends that is your family, your chosen family, and very often your community of friends might be your ex-lovers also…that is certainly true in my personal life. That is what the sequel is about. Jimmie LeRoy and the ex-lover get together and they review and rehurt each other in ways that they had really damaged each other before. But, ultimately, they both need the help of each other and they both come through for each other because that kind of love… that kind of family…those bonds cannot be broken.

Home in Her Heart plays through March 10 at Stage Left Studio.