Alia Kache’s Caricature of She is a painfully accurate depiction of “femininity” as an absurd, out-dated, and tiresome notion. This notion brainwashes many women into striving for “perfection” at the cost of their individuality and natural beauty. And because “perfection” is a false ideal and endless goal, women who buy into and perpetuate this notion are inevitably unempowered. The Barbie doll, the fembot, the female comic book character are all ultimately subservient to patriarchal authority.

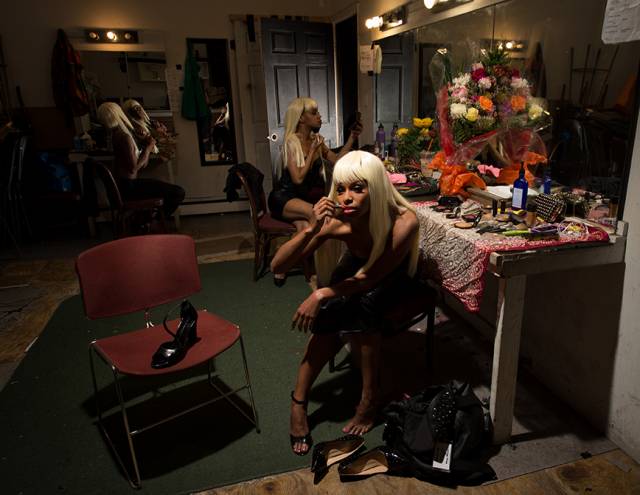

The 50-minute dance, performed at the New York International Fringe Festival, opens begins with five women in a single file line walking and gesturing throughout the stage in unison. They wear the same three-inch high heels, the same tight, knee-length dress, and the same long blond hair. A large mirror-type prop on casters is rolled around the stage as the dancers find new formations and execute highly postural movement: arms swoop around hair, spines ungulate, hips shift and roll, chests pop outward and inward. Individuality does not exist in this world—instead, women are eroticized, passive, “ideal” women who look and move the same. We can infer that if they were to speak, they would sound the same and choose the same words. But according to audio recordings that play over electronic music, speaking is not important anyway.

Kache uses audio from two 2012 YouTube videos that remind us that this caricature is still highly pervasive in our society. According to Coach Corey Wade, “expert” on gender and relationships, women are for the purpose of men. I clench my jaw at his voice that explains why feminine women are hot and why men lose interest in “masculine” women—women who are not submissive, passive, and vulnerable. He places an enormous amount of importance on physical appearance. “Men are visual creatures” who want a woman who “acts like a sex symbol…a vulnerable, sexy princess.” Another audio segment is from a video titled “Perfect 10 Face,” based on Diana Polska’s book “All Women are Beautiful.” We listen to women’s voices explaining at length how to change an imperfect face into a “perfect” one—in other words, all women can be beautiful if undergoing plastic surgery.

Kache presents a juxtaposition of becoming a “perfect 10” and being yourself, both of which are complicated realms of existence. Being yourself is easy for those exhausted by constant demands—the first dancer simply takes off her wig, the tight dress, and the high heels. But breaking away from a group can be a lonely road; liberation prompts ridicule and criticism: “you are not following the rules,” one gestures to another. Breaking away also means finding out who you are without the group. Wearing simple nude leotards, their movement becomes much more dynamic and expressive, poetic and athletic, finally unrestricted by tight dresses and high heels. Having made the decision to define beauty for themselves, the women are faced with name-calling and dirty looks, continually pressured by full-length mirrors, and still taunted by descriptors, such as “sexy” and “baby.” When the fourth dancer sheds her layers as well, we begin to wonder if the fifth will follow too. But truth be told, not all women will make it to the other side. In the end, a single dancer remains in her opening attire, facing the mirror up stage. She shakes her hips and rolls her body, looks over her shoulder, and smiles seductively at the audience.