BAM is embarking on a retrospective of one of cinema’s most elusive, idiosyncratic, and brilliant auteurs, Chris Marker, beginning with the U.S. theatrical premiere of one of Marker’s lesser seen works, Level Five. There’s a certain irony in calling one of Marker’s works “lesser seen,” since all of his films were famously hard to see in the decades of circulating film prints and even in the age of the internet, Marker is lesser seen than his contemporaries simply because of the impossible to categorize nature of his films and of the man himself. Marker was an enigma who made enigmatic films, formally innovative essay films that are all-encompassing through their digressiveness; whatever subject Marker might begin with was soon enfolded with musings on memory, the nature of the image, cultural change, love, war, and everything in between, usually with some cats included (Marker, who would never allow himself to be photographed, would offer a picture of a cat as a stand-in, because cats are never on the side of power).

BAM is embarking on a retrospective of one of cinema’s most elusive, idiosyncratic, and brilliant auteurs, Chris Marker, beginning with the U.S. theatrical premiere of one of Marker’s lesser seen works, Level Five. There’s a certain irony in calling one of Marker’s works “lesser seen,” since all of his films were famously hard to see in the decades of circulating film prints and even in the age of the internet, Marker is lesser seen than his contemporaries simply because of the impossible to categorize nature of his films and of the man himself. Marker was an enigma who made enigmatic films, formally innovative essay films that are all-encompassing through their digressiveness; whatever subject Marker might begin with was soon enfolded with musings on memory, the nature of the image, cultural change, love, war, and everything in between, usually with some cats included (Marker, who would never allow himself to be photographed, would offer a picture of a cat as a stand-in, because cats are never on the side of power).

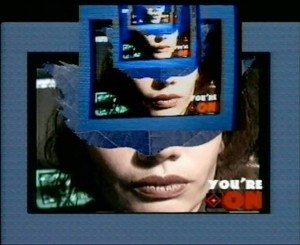

Level Five is considerably obtuse and difficult, even compared to other Marker films, feinting in one direction only to have the protagonist enjoy a scene with a toy parrot instead. The protagonist is a woman named Laura (Catherine Belkhodja), who toils away in a dark room trying to finish programming a video game about the Battle of Okinawa that her lover left behind when he died. Among her coterie of machines, Laura muses on life while wrestling with death, both in her personal, immediate mourning for her lover and on the world-historical level, as she learns more about the horrors of Okinawa. The film features footage that Marker shot while exploring the island in the 80s, interviews from Japanese survivors, American footage, along with some proto-CGI that was primitive at the time (the film is from 1995) and looks positively prehistoric now. The computer elements show just how prescient Marker was in his embrace of new media and digital technology for an artist born in the early 1920s (particularly prophetic – calling the computer a spirit that keeps all of our memories for us).

Marker delights in the possibilities of these new forms, though he pointedly denies that they offer any escape from our past; the video game keeps resisting commands to change the outcome of the battle and in every recreation, Okinawa arrives at the same tragic conclusion. Marker’s layers of obfuscation keep the audience at arm’s length from the true horror of the events, except at key moments when it cannot be kept at bay. About a third of the island’s civilian population died in the battle, many encouraged to by government authorities to commit suicide instead of falling into the hands of “yankee devils.” One interviewee recalls the moment, as a teenager, when his mother and sisters looked at him, expecting him to kill them for their own protection. Honor-bound, he complied, and lived with that memory for sixty years. On the American side of the conflict, Marker shows shattering footage shot by John Huston while in the army, censored by the U.S. for thirty years, of an Okinawa veteran whose memory is completely gone, who recoils in terror when hypnosis is used to unlock the memory of fighting at Okinawa.

Level Five is the work of a playful intelligence meditating on weighty themes. Its digressions and disguises can be frustrating, but reward the viewer for forgetting their preconceived notions and narratives and allowing Marker’s film to make its strange connections.