John Huston was a true Hollywood legend – a maverick writer who by sheer force of talent and personality made the then unheard-of transition to directing in the early 1940s, only to continue writing and directing films for the next five decades. Huston’s life was just as colorful and adventurous as his films; before settling down in Hollywood, Huston was a boxer, a cavalry rider in Mexico, a reporter, an actor, and a painter in Paris. Huston brought all of those experiences to life on the screen, leaving behind a body of work as diverse and fully realized as any in film. Huston also was a talented interpreter of fiction, both modern and classic, tackling film versions of such difficult novels as Moby Dick, Wise Blood, The Red Badge of Courage, Fat City, and Under the Volcano. Lincoln Center is honoring Huston with an upcoming retrospective and to prepare you, we’ve made a list of Huston's best films.

John Huston was a true Hollywood legend – a maverick writer who by sheer force of talent and personality made the then unheard-of transition to directing in the early 1940s, only to continue writing and directing films for the next five decades. Huston’s life was just as colorful and adventurous as his films; before settling down in Hollywood, Huston was a boxer, a cavalry rider in Mexico, a reporter, an actor, and a painter in Paris. Huston brought all of those experiences to life on the screen, leaving behind a body of work as diverse and fully realized as any in film. Huston also was a talented interpreter of fiction, both modern and classic, tackling film versions of such difficult novels as Moby Dick, Wise Blood, The Red Badge of Courage, Fat City, and Under the Volcano. Lincoln Center is honoring Huston with an upcoming retrospective and to prepare you, we’ve made a list of Huston's best films.

Huston’s adaptation of Flannery O’Connor’s pitch-black Wise Blood updates the story to a modern setting but loses none of the novel’s disturbing perspective on American faith. Seeing the events on the screen foregrounds the comedic aspects of the story but Huston never loses sight of the fact that Hazel Motes’ (Brad Dourif) struggles with religion are a matter of life and death for him, that he is playing out in a public and deranged way. Dourif stars along with the great Harry Dean Stanton as Asa Hawks and Amy Wright as Sabbath Lily to complete O’Connor’s gallery of American gargoyles. With Wise Blood, Huston proved yet again that he could get to the heart of difficult novels like no other director.

Before Rocky, before Raging Bull, there was Fat City, Huston’s adaptation of Leonard Gardner’s under-read boxing novel that doesn’t make boxing look life-changing or operatic, but just another painful way to make a buck and try to get by. Starring Stacy Keach and a very young Jeff Bridges as two boxers at opposite ends of their careers. Fat City takes place in Stockton, CA, portrayed as a dusty, dead-end town with little to offer but migrant farm work and desperation. Huston takes his life-long fascination with losers playing out the string and gives the yearning of these has-beens and never-was’s a gentle poignancy.

Of all of Huston’s films, The African Queen is probably his most quintessential Hollywood entertainment. Starring two of the world’s greatest movie stars, Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn, as a rough riverboat captain and a straight-laced missionary in Africa during World War I. The contrasting styles of both actors bring out their best as they travel down the river finding action and romance. This was Bogart’s fourth collaboration with Huston as a director (Huston also wrote the screenplay of Bogart’s breakout High Sierra) and the film that finally netted Bogart a Best Actor Oscar.

Under the Volcano stars Albert Finney in a career defining performance as an alcoholic former British consul, battling his demons through drinking on a long Day of the Dead in Cuernacava, Mexico, 1938. Finney's character, Geoffrey Firmin, is a committed alcoholic, who must drink steadily just to attain a moment of lucidity, and who thinks nothing of waking up in the middle of the street, as he does in one scene that’s downplayed with a hilariously English sense of decorum. Geoffrey is mourning the loss of his wife, whom he misses dearly but whose letters he can’t bring himself to read, leaving him totally unprepared when she actually does return. Despite his affliction, she still loves him and they talk optimistically of a new start, but with a mournful knowledge that this is no longer really possibly. Huston’s location shooting finds beautiful visuals to accompany the story from Malcolm Lowry’s novel, eschewing most of the political subtext to focus entirely on one man’s vivid dissolution.

The Asphalt Jungle’s most famous line is probably, “After all, crime is just a left-handed form of human endeavor.” Huston endowed his criminals with a humanity and pathos many other directors denied theirs. It’s a thrilling caper flick that never sensationalizes its subject, and doesn’t use the heist as the climax, but rather the beginning of a series of small accidents and all too human failings that undo the gang of criminals. Another one of Huston’s films about men who succeed in a goal, only to fall apart after reaching the goal.

Usually film noir calls to mind poorly lit alleys and dingy apartments, but in Key Largo, Huston takes the noir aesthetic to the sandy, palm-lined southern tip of Florida without missing a beat. Huston imbues his setting with a sweaty menace even before the hurricane blows in, forcing strangers to take shelter together with lethal consequences. Bogart plays a war hero, disillusioned by the America he’s come back to, drifting into Key Largo both to see the family of a fallen soldier and because it’s the end of the line. Edward G. Robinson is an exiled gangster, back on American soil for the first time in years and willing to leave behind as many bodies as necessary. Lauren Bacall plays the widow of Bogart’s army friend, trying to protect the new life she’s built and believing in Bogart more than he does himself. Key Largo is a relentless suspense film that asks at what point must an ordinary man stand up and fight, not for himself, but for the good of the world.

Like Under the Volcano, The Night of the Iguana features a boozy gringo at the end of his rope in Mexico, but the problems of the two men take a much different tenor. The Night of the Iguana stars Richard Burton as the defrocked Rev. T. Lawrence Shannon. Chased out of his church and America for an underage dalliance (related in an unforgettably surrealistic flashback), Shannon is leading bus tours of Mexican religious sites to American housewives. After he again flirts with temptation and begins to lose control of the group, he hijacks the tour and takes them to Ava Gardner’s hotel, where he undergoes a long, dark night of the soul with the sympathetic traveler Deborah Kerr. Burton’s performance is a wonderful mix of hammy overacting and genuine anguish. Huston uses the beauty of Puerto Vallarta to bring Tennessee Williams’ play to life, voicing through Shannon the struggle to find and nurture belief in an uncaring world.

This tale of fun-loving colonialists is even less P.C. now then when it was released in 1975, but it’s also a perfect embodiment of the larger-than-life adventure film that Hollywood doesn’t make anymore, with real locations and real action. Adapted from a Rudyard Kipling story, The Man Who Would Be King stars Sean Connery and Michael Caine, in one of the greatest all time screen pairings, as two former British Army officers who decide to risk life and limb to travel to a remote mountain kingdom, “where no white man has set foot since Alexander,” and claim the throne. After a stunningly shot mountain journey, the two use their tactics and firearms to take power, after which some lucky coincidences (hint: Freemasons!) result in Connery being proclaimed not just king, but God, a hubris that costs him dearly. Huston waited years to make this film, and I’m glad he did, because it seems impossible that any pair could have the natural rapport that Caine and Connery have in this film. Their goals are despicable, but their rakish manner, their complete lack of fear in the face of incredible danger, and their total honesty with each other makes them winning protagonists in this story of high adventure.

The Maltese Falcon was Huston’s first film as director, but he was ready, having honed his craft as a writer for years and sketching out every shot in order to make the most of his chance at directing. The result is arguably the first and inarguably one of the greatest noir films, starring Humphrey Bogart as Dashiell Hammett’s private eye, Sam Spade. Spade is a hard man, but one with a code; someone killed his partner and he wants to do something about it. The lighting and camera set-ups are simply stunning for a first-time director. This is one of those films that’s harder to appreciate in retrospect because it set the tone for so many later noir films, starting with Bogart’s wonderfully dark and nuanced Sam Spade, which cleared the way for a new kind of protagonist for the 1940s.

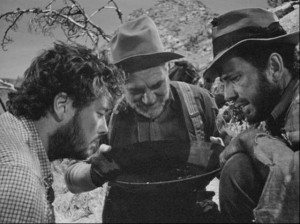

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

In The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Huston uses adventure and discovery as a test of mens’ souls and finds them wanting, concocting a grand drama out of our most negative emotions: fear, greed, jealousy. This is one of Huston’s darkest and greatest films, for which he won the Best Director Oscar, starring Bogart in an ego-less performance as the conniving Fred C. Dobbs and co-starring Huston’s father Walter. The story revolves around a group of men traveling to Mexico (one of the first Hollywood location shoots and the beginning of Huston’s cinematic love affair with the country) looking for gold. They’re hard up before they go and even harder up afterwards, as betrayal and deceit tears the group apart. The film plays out like a sun-baked and mud-caked Shakespearean tragedy, culminating in as much despair as King Lear or Othello.