Most documentaries on politics and science don’t open with scenes from a magic show, but Merchants of Doubt uses intermittent interviews with a magician as an ingenious framing device to show how a new breed of PR mercenary is using the same tricks he does to bamboozle the American public. Merchants of Doubt centers on the wide variety of industries whose profits are collected at odds with the scientifically verified public interest and the tactics they use to discredit that science.

Most documentaries on politics and science don’t open with scenes from a magic show, but Merchants of Doubt uses intermittent interviews with a magician as an ingenious framing device to show how a new breed of PR mercenary is using the same tricks he does to bamboozle the American public. Merchants of Doubt centers on the wide variety of industries whose profits are collected at odds with the scientifically verified public interest and the tactics they use to discredit that science.

The founding principle of this new profession is that while it maybe illegal to use PR and advertising to flat out deny science, it’s perfectly legal to use any means at your disposal to cast doubt on that science, whether it’s ad hominem attacks on scientists, paying your own scientists of dubious credentials, or setting up entire think tanks to pump out propaganda for your cause and against science.

The timeline of the doubt industry is fascinating, because it originated in the 1950s, as the tobacco industry began to face evidence that its product was killing people. Despite what they claimed for decades afterwards, industry insiders knew and accepted that verdict in the 1950s, when they withdrew their ads claiming medical benefits of smoking and began instead to obfuscate the claims made by anti-smoking activists. Now, of course, pretty much everyone, smoker or not, knows that smoking is verifiably bad for you, but it took almost fifty years for that consensus to emerge, during which time hundreds of millions died preventable deaths and tobacco companies continued to earn billions of dollars in profits.

Other industries saw how effective the tobacco industry’s efforts were and hired the same people to dupe the public on their behalf. Most notably, the oil industry set out to deny that their product was causing climate change and putting our entire planet at risk. Despite using the same playbook and many times the same professionals as the tobacco industry, many people refuse to believe that this is all another PR diversion, instead indulging in paranoid fantasies that liberals created global warming as a hoax.

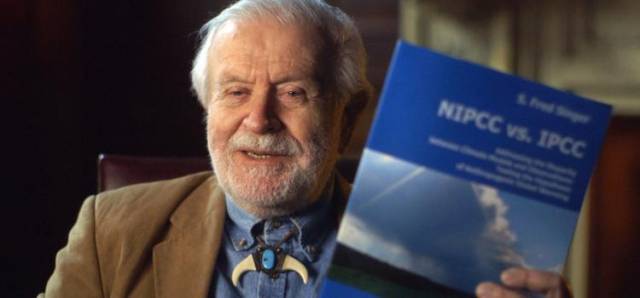

Merchants of Doubt exposes many fascinating aspects of the intersection of politics and science. First, how the willingness of the American public to look only at the most superficial aspects of claims before deciding their validity has enabled this shift. Many accept junk science because it’s cloaked in the presentation styles of real science, such as a Cato Institute pamphlet that mimicked a similar report from NASA down to the color scheme and page layout. Furthermore, many prefer to listen to more telegenic PR people than actual scientists because actual scientists are usually by their nature not very good at public presentation.

Another aspect is tribalization. For many conservatives, climate change denial is part and parcel with the rest of their beliefs, as former South Carolina congressman Bob Inglis discovered when he took a look at the data and decided that maybe climate change was real. He found few if any conservatives willing to look past party dogma, because it interfered with their conservative identity on a basic level, science be damned. While most of the “scientists” that deny climate change are barely accredited, the filmmakers wondered why two prominent scientists were willing to support the cause. They discovered that these physicists were relics of the Cold War and were fervent believers that any government regulations of industry, such as environmental protections, were steps on the road to communism.

Merchants of Doubt is a well-made, entertaining, and thoroughly necessary documentary. The engineering of doubt has already polluted the public mind and prevented our scientific community from using their findings to promote our health and well-being. Hopefully, through showing people the mechanisms used, Merchants of Doubt can help prevent this in the future, but as the film shows, people mostly listen to only what they want to believe.