Some degree of reckless ambition is needed in a director to create something truly original, but it’s endearing to see that ambition tempered with humor, compassion, and personal humility. Early in Miguel Gomes’ Arabian Nights (which can be considered either a trilogy or simply one six-hour movie), after a series of portentous titles marking the film as an attempt to use the structure of the ancient story cycle to show the austerity-dampened climate of modern, post-recession Portugal, we see Gomes himself literally running away in fear from his film crew and his epic task. Luckily, he seems to have been lured back to the set to create this beguiling triptych, which never shies from its subject of financially diminished Portugal, but tackles what could be a dour subject with warmth, humor, empathy, inventiveness, passion, and a sense of wonder.

Some degree of reckless ambition is needed in a director to create something truly original, but it’s endearing to see that ambition tempered with humor, compassion, and personal humility. Early in Miguel Gomes’ Arabian Nights (which can be considered either a trilogy or simply one six-hour movie), after a series of portentous titles marking the film as an attempt to use the structure of the ancient story cycle to show the austerity-dampened climate of modern, post-recession Portugal, we see Gomes himself literally running away in fear from his film crew and his epic task. Luckily, he seems to have been lured back to the set to create this beguiling triptych, which never shies from its subject of financially diminished Portugal, but tackles what could be a dour subject with warmth, humor, empathy, inventiveness, passion, and a sense of wonder.

Gomes does not adapt any of the specific tales of the Arabian Nights; he takes only its framing device (Scheherazade telling stories to her husband, the King, to forestall her execution), its chaotic energy, and and its mix of subjects. The film is a marvel of tonal control; Gomes somehow manages to merge ancient and modern sensibilities without feeling false to the world he’s created – a world where bankers interact with wizards, or where a bird-trapper might apathetically free a wind genie from his net and turn down a 20 euro reward. While the anthology format makes it easy to enjoy one without seeing the others, the utterly unique mixture of fable and docudrama marks each volume as a component of the whole.

Volume One: The Restless One begins by detailing the working conditions of several trades: dock workers who have just been laid off, a wasp remover searching for new techniques, and Gomes himself with his film crew. The tone is set quickly as this transitions into perhaps the silliest of the tales, “The Men with the Hard-Ons,” which dramatizes a meeting of IMF men with members of the Portuguese government to hammer out details of the austerity arrangement. Their punitive resolve is weakened when they meet a wizard who spontaneously offers them an aerosol potion to restore their erections, leaving the men overjoyed at first. Other segments in the first volume involve a New Years swim featuring heart-rending stories of the newly unemployed and a teen romance that ends in arson. That crime is reported to a judge by a talking rooster who is on the chopping block for crowing at all times of the night, in an effort, he explains to the judge, to warn others of the fires. In certain segments, the poetic imagery of stunning seascapes loosely tethered to the audio track combined with a sense of intellectual playfulness recalls late Godard, but Gomes is less obtuse and more humane, even as he pursues his themes unfettered by any sense of narrative obligation.

Volume Two: The Desolate One opens with a trek through rugged terrain in the tale of the outlaw “Simao without Bowels.” Despite being by all accounts a selfish asshole, Simao manages to become a folk hero by eluding the even less popular police. The next tale is perhaps the strongest of Arabian Nights, a nested series of stories told to a judge in an open-air amphitheater. What begins as a straightforward trial takes a bewildering amount of turns as more and more members of the crowd speak up with complicating details. A dream-logic that confounds cause and effect takes hold as the story expands to include everything from ancient bandits speaking through demon masks to a Chinese businessman in Portugal for the lax visa restrictions. The last segment will probably be the favorite of viewers more desirous of the political docudrama elements as it takes a panoramic view of the residents of a large apartment building. The adorable dog Dixie links the residents as he is shunted from family to another due to widespread financial problems leading to death and dissolution. Even while dealing with the saddest themes of the film, the tone remains, if not upbeat, then defiant, determined like Dixie to keep finding joy and striving to live in reduced circumstances.

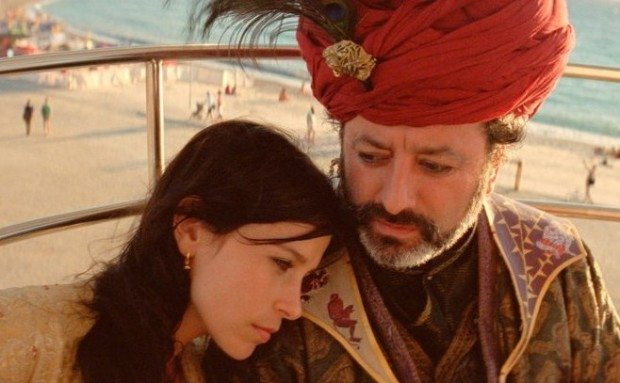

Volume Three: The Enchanted One opens with Scheherazade herself, reflecting on the irony that though she spends each night telling wildly diverse stories, she herself has led a mostly confined life and scarcely seen the wonders she describes. Probably the most sensual and romantic interlude, she walks the shores of ancient Baghdad and meets characters such as the prodigiously virile Paddleman and a compassionate thief named Elvis. After this sun-drenched opening, Volume Three might be the driest of the volumes, as almost all of the remainder concerns men capturing songbirds and entering them in singing competitions, a pursuit which is portrayed with a documentary-like level of detail. Gomes seems to transition away with a story about a Chinese immigrant, but then returns to the songbirds, deliberately frustrating expectations of an explanatory denouement.

Arabian Nights is such a freewheeling and epic compendium of styles and subjects that it is difficult to compare it to any other film. It’s easier to compare it to the tradition of massive, endlessly digressive novels, whether by postmodern authors like Pynchon or Wallace, or by authors inventing the form as they went along, like Sterne or Cervantes. Like those writers, Gomes’ imagination is not limited by anything other than the attention of his audience, which never wavers despite the size and strangeness of the endeavor. Even with this experimental aspect, Gomes never forgets that his film is a testament to the spirit and resilience of the Portuguese people and a howl of protest against the policies that forced the recession upon them. Arabian Nights is a new form of political cinema, but more than that, a bold new form of cinema.