“If I could write a screenplay about my life,” says Choi Eun-hee, the 89 year old South Korean actress, “I would only include the glamorous shots.” Lucky for Choi, she’s the star of Rob Cannan’s and Ross Adam’s engrossingly glossy doc, The Lovers and The Despot. Lucky for us, Choi is also our escape from the doc’s sometimes overly-slick storytelling.

“If I could write a screenplay about my life,” says Choi Eun-hee, the 89 year old South Korean actress, “I would only include the glamorous shots.” Lucky for Choi, she’s the star of Rob Cannan’s and Ross Adam’s engrossingly glossy doc, The Lovers and The Despot. Lucky for us, Choi is also our escape from the doc’s sometimes overly-slick storytelling.

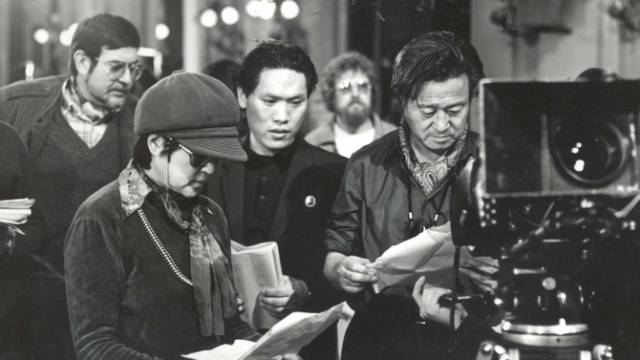

The story itself is incredible: in the 1950s, Choi and her late husband, prolific South Korean filmmaker Shin Sang-ok, fell in love on a movie set, got married and adopted two kids. Then a younger actress popped up. Shin cheated. Choi was heartbroken. Their marriage faltered. But things reached a new level of bad in the 1970s, when North Korean agents kidnapped Choi and Shin. They remained separated for five years – that’s how long Kim Jong-il, heir of the country’s then supreme leader, Kim Il-sung, and his father’s imminent successor, took to reunite the couple after orchestrating their original abductions. He then made them an offer they couldn't refuse: to produce movies, more movies and even more movies for Kim until North Korea became an envied empire of cinema. That empire didn't come to be, but Shin’s and Choi’s movies did – a whopping 17 of them, in fact. All the while, Shin and Choi plotted their escape. Knowing many would doubt their story back home and perhaps around the world, they also made secret tape recordings of Kim to prove he had ensnared them.

Cannan and Adam use fascinating sound-bites from those tapes and a number of other effective narrative-devices – reenactments, a suspenseful score from composer Nathan Halpern, interviews and film footage, among them – to give The Lovers and The Despot a sense of suspense and – perhaps to Choi’s liking – glamour that sometimes feels forced.

But thankfully, Choi has been in enough movies to know the drill. Donning rose-tinged glasses that mostly hide her movie-star eyes, Choi always seems in on the fact that Cannan and Adam are making entertainment out of her real-life melodrama. Sometimes she is jiving with it – like when Choi regales us with the tale of her action-packed abduction from Hong Kong or of her and Shin’s escape attempt in Austria, worthy of a slow-motion sequence. Other times, Choi shows that not every event was thrilling, especially the ones you might expect to be, like when she and Shin see each other for the first time after five years apart. “If it were a movie, it would have been a tearful moment,” Choi says of their conservative reunion. She also shares moments of downright ugliness, perhaps none uglier than when Kim invites Choi to the screening of a film, at the end of which, a traitor is shot in the back. Choi took the hint, she says.

Choi’s vignettes reveal themselves like a Matryoshka doll – appropriately bringing verisimilitude, artfulness and flair to The Lovers and The Despot, as well as the sad longing for life to be more like a great, romantic film than a nightmare of repression, captivity and fear.