Genocide. Few would argue that its prevention is not a moral imperative, yet it is so sickening and unknowable, that many would rather ignore it than face it head on. Genocide and this inherent tension form the subject of a devastating new documentary, Watchers of the Sky. The heart of the film is the story of Raphael Lemkin, who coined the word genocide and spent his entire life attempting to use the law to preclude it from ever happening again. A legal prodigy and Polish Jew born in 1900, Lemkin and his family suffered upheavals during the first World War, but what really commanded his attention and outrage was the plight of the Armenians, over one million of which were systematically exterminated by the Turkish government in a massive crime that received little attention in war-torn Europe. From his legal standpoint, Lemkin began to ask his peers, “Why is the killing of a million a lesser crime than the killing of an individual?”

Genocide. Few would argue that its prevention is not a moral imperative, yet it is so sickening and unknowable, that many would rather ignore it than face it head on. Genocide and this inherent tension form the subject of a devastating new documentary, Watchers of the Sky. The heart of the film is the story of Raphael Lemkin, who coined the word genocide and spent his entire life attempting to use the law to preclude it from ever happening again. A legal prodigy and Polish Jew born in 1900, Lemkin and his family suffered upheavals during the first World War, but what really commanded his attention and outrage was the plight of the Armenians, over one million of which were systematically exterminated by the Turkish government in a massive crime that received little attention in war-torn Europe. From his legal standpoint, Lemkin began to ask his peers, “Why is the killing of a million a lesser crime than the killing of an individual?”

Lemkin devoted himself to building a legal framework to prevent such a crime, but was impeded by a consensus that whatever a sovereign state does within its own borders is de facto legal. The film shows fragments of Lemkin’s notebooks, accentuated with minimalist, yet evocative animations, to beautifully portray the evolution of his thinking. Unfortunately for Lemkin and the rest of the world, his subject was soon to recur again. Lemkin was able to see the signs all too clearly and emigrated to America, but was unable to convince his family to leave before World War II and the final solution killed everyone in Lemkin’s family along with six million other European Jews.

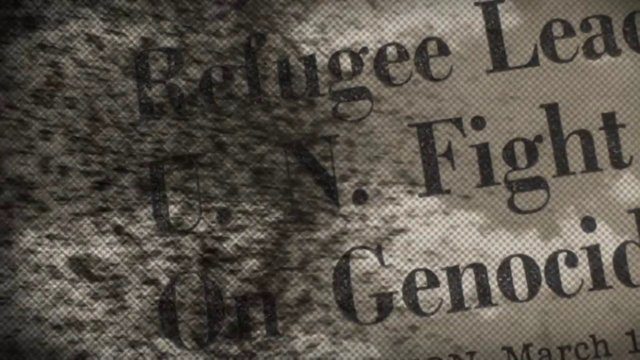

A haunted man after losing everyone and everything he knew to the Holocaust, Lemkin poured every ounce of his energy into his cause, at the expense of his own health and well being. The horrors of the war and the formation of the United Nations in his new hometown of New York provided Lemkin with both the societal momentum and global platform to make his case. He correctly intuited that his argument would be more persuasive with a more definite name for the crime and concocted “genocide.” His greatest success was the passing by the UN of the Genocide Convention, outlawing the heinous crime.

His story is in many ways tragic – his funeral was sparsely attended, after he died at an NYC bus stop on one of his near-daily trips to the UN. But the greatest tragedy is that genocide continues to occur regularly in our world today, despite Lemkin’s efforts and universal condemnation. Watchers of the Sky also profiles and interviews four contemporary figures in the fight against genocide. Ben Ferencz served as a young man in the U.S. army under General Patton and witnessed the liberation of some of the concentration camps. After the war, he was chosen to prosecute at the Nuremburg trials, where he, like Lemkin, attempted to build a legal framework against an almost inconceivable crime. Samantha Power is a current American ambassador to the United Nations and cut her teeth as a war correspondent during the Bosnian genocide, where she saw first hand the unwillingness of modern media and society to look the problem of genocide in the eye. Emmanuel Uwurukundo survived the Rwandan genocide, but lost his entire family and questioned his entire existence. His story is one of the most powerful, as a first hand witness to unthinkable violence. He sums up the survivor’s mentality, “You have two choices. Either you come to the conclusion that life is meaningless…that you are dead to the word, without hope. Or you think that if I am still alive, there must be a reason for it. There must be something I can do with my experiences to make things better.” To that end, Uwurukundo runs refugee camps in Chad, taking in survivors of the genocide in Darfur. The final contemporary subject is Luis Moreno Ocampo, the chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, which in many ways is the manifestation of Lemkin’s vision. Ocampo broke with his own family in Argentina to stand against the horrors of the military junta and continues to thanklessly fight against global injustices. The film shows his efforts to indict Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir for the ongoing genocide in Darfur. The ICC is reliant on member nations to carry out its verdicts, and despite the fact that Ocampo is fulfilling his duties to the letter, political and economic concerns have kept the courts verdicts from being acted upon and innocent people continue to die in Darfur.

Watchers of the Sky is exceedingly difficult yet urgently necessary viewing. It’s well made and deftly intertwines its various threads, yet these aesthetic concerns are dwarfed by the moral enormity of the crimes it portrays. It’s easy to feel dispirited by the film’s end, as the recurring and ongoing history of genocide shows little chance of ending soon, but the film’s final moments make clear the meaning of the title, as Ferencz tells a story about Tycho Brahe. Brahe spent most of his life recording data that nobody knew saw and use for at the time, yet centuries later have formed the basis of entirely new disciplines and ways of seeing the world. We can only hope that years later the work of Lemkin and Watchers of the Sky’s other subjects will form the basis of a world free of genocide.