In the Bar of a Tokyo Hotel, Tennessee Williams’s 1969 one-act (two scene) play, is such a dark, bitter work that it would seem wrong to call seeing it a “rare treat.” But the current production (at the tiny 292 Theatre in the East Village) will be a welcome event for anyone interested in the more arcane corners of the Williams canon.

The play is about the disintegrating relationship between a once-successful painter, Mark (Charles Schick), and his now-scornful wife, Miriam (Regina Bartkoff). Williams composed the play during a particularly troubled patch of his life. He fretted during the mid-to-late 1960s that his way of writing plays was obsolete and that his star had been eclipsed by the work of newer artists, including Harold Pinter and Edward Albee. (There are echoes in Tokyo Hotel of Albee’s “Snap!” monologue for Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?—only with Miriam, the key word is not “snap” but “snuff.”) Williams kept writing plays during what has become known as his “Stoned Age,” but they were largely dismissed—and frequently savaged—by critics. Not surprisingly, he drank and drugged heavily during this time.

Schick and Bartkoff previously appeared in a 2012 production of the play, also at 292 Theatre. This new incarnation (seen in 2016 in Provincetown, MA) has been directed by Everett Quinton, who lends the proceedings a robust theatricality. For instance, he embellishes a stage direction Williams included about wind chimes. Whenever Miriam edges toward emotional unraveling, she grasps her head in her hands, overcome by a mad jangling sound.

Schick’s turn as Mark (clearly a stand-in for the disintegrating Williams) is reason enough to see the show. His hand trembles and his eyes have a demented look. He pitches about the small stage like an unmoored ship in rough waters. He’s thoroughly believable as a painter both obsessed by and terrified of his art—a man who considers himself the Columbus who discovered color, but who is simultaneously terrified by this new world. Schick makes Mark look like a man who’s spent years breathing toxic paint fumes, leaving him in a perpetually altered state.

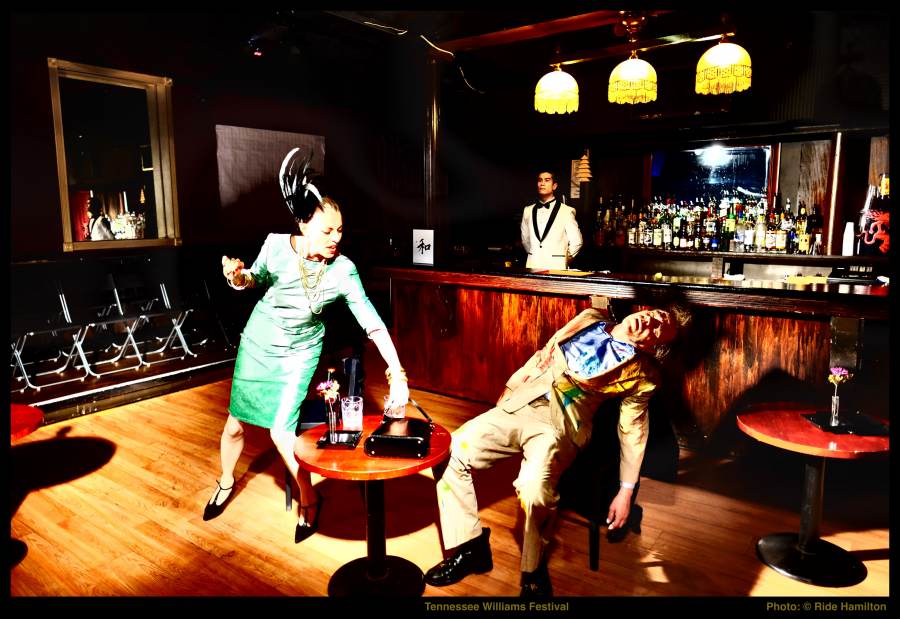

Bartkoff also gives a watchable performance, though it can’t be a picnic playing a role that writer John Lahr has identified as “the unsparing, objectifying voice of [Williams’s] own self-loathing.” She’s a bit fitful in the earlier scenes, in which Miriam tries to seduce an unwilling barman (Brandon Lim). At times, she suggests what Mae West might have done with the role of Blanche DuBois. Fortunately, she rises to the occasion in the second half, effectively delivering some caustic, chilling speeches. Throughout the play she is something to behold. She sports feathered headpieces that give her the aspect of an exotic bird of prey. (Or perhaps she’s some sort of plumed scavenger: Miriam is open about her intention to feed on her husband’s legacy once he is safely dead.)

Mark and Miriam are pretty much the whole show. Lim’s barman seems mostly on hand for comic effect. Wayne Henry shows up as Leonard—a gallery owner whom Miriam summons from New York to Tokyo to deal with the last of her broken husband. He also has a recurring cameo as a hula-ing female tourist from Hawaii—in sequences that, again, seem to show Quinton’s hand.